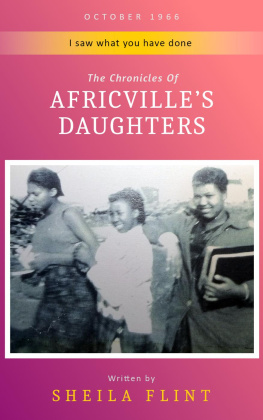

AFRICVILLES DAUGHTER

I Saw What You Have Done

By Sheila Flint

All material contained herein is Copyright Sheila Flint 2019.

All rights reserved.

Originally published in [language] by [Publishing House] as [Title].

Translated and published in English with permission.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 7750906_0_1

Written by Sheila Flint

Cover art by Ashutosh Mishra

Edited by DeeDee Quigg

Translated and published in English with permission and in association with Aficha Virtual Assistants Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without prior written permission of the Author. Your support of Authors rights is appreciated.

This book should not be used for legal advice.

First Edition

I ntroduction

Chapter One Eight Years Old

Chapter Two Around Africville

Chapter Three Precious Memories

Chapter Four Eleven to Twelve Years Old

Chapter Five The Relocation

Chapter Six Remembering Africville

Chapter Seven Thirteen to Fourteen Years Old

Chapter Eight Montral

Chapter Nine Death in the Family

Chapter Ten Graduation

Chapter Eleven Africville Reunions

Chapter Twelve History Lessons

Chapter Thirteen The Apology

Chapter Fourteen The Class Action Lawsuit

Chapter Fifteen Africvilles Daughter

Conclusion

For every purchase made, an amount goes to Heal the World Today Project to continue their great work. In order to help at least one person to heal from their traumatic experiences by showing them the art of self- healing through various methods and reminding them that they are not what happened to them.

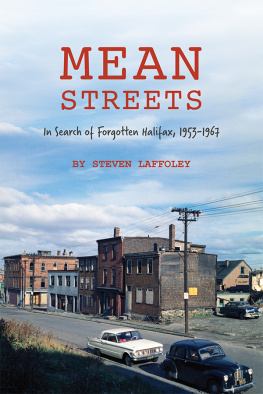

M y home, Africville . It's where I was born. Most people know the history of Africville and what was done to the people, how we had dreams, and how our people were moved out of our homes on the back of city dump trucks. Theyve heard about how people tried to take their belongings with them, whatever they could get on the back of the trucks, how places were being bulldozed down as fast as could be. They know how they were taking people out of their homes for development with no thought of the people's emotional state. But there is a lot they dont know. They dont know my story the story of Africvilles daughter.

My name is Sheila Flint. I was born at the Victoria General Hospital in Halifax on October 29, 1951, at 6:30pm.

I was raised in Africville, lived there with my parents. Every neighbor, to me, was a family member. My grandmother and grandfather also lived there, along with uncles on both sides of the family, and cousins, sisters, and brothers. I lived in a part of Africville called Bigtown. There are no pictures of Bigtown that I could find.

In the summertime, my friends and family would fish, swim, make a bonfire on the shores of Bedford Basin, cook lobsters, crabs, muscles, and penny winkles. This was what we knew life to be until 1966, when the city of Halifax rushed in with their longstanding plan, known as "urban renewal, to get our families out of there. They needed to do this before the young ones grew up, when it may have been harder to get the land from us. Urban renewal sent everyone in different directions, including me.

I stayed with a few people here and there, in the city and outside it, never lasting too long. Eventually, I moved to Montral and made another life there. But, in moving, I just carried Africville with me. It lives in me.

Eight Years Old

A s a young girl, I remember settling in the grass in the back of my parents home up a hill in the back of the community, facing the homes of my extended family homes. I would sit there, looking down the hill at the beauty of the ocean, watching the waves as the ships sped passing by down yonder. Around me, on the land, were bushes of blueberries, green grass, tall trees in blocks, short ones, big ones, thin ones, and tiny little ones.

I would look over and down to where I lived; my home.

Between me and my home, there were dry walkways between the other homes. I could see aunts, uncles, and other Black families there. It was a Black community. Only one family was white, as far as I know.

I turn back to the ocean where the ships seem to be moving faster. I wondered where they were going and why. I couldnt ask them where they were going because they were out in the ocean. I would wave to them sometimes and they would wave back. I just never really thought about asking anyone, Where are those ships coming from? We also had boat shows of some kind in the summertime. I see this same scene often in my mind.

***

B ack then, I would always go walking alone. This was one of my special places to go, in the back of my parents house up on a hill in between my moms and my maternal grandmothers house. I would just sit on the green grass and think and smell the fresh ocean air. How I did appreciate the silence. I just knew that this feeling was something that I really liked. There is nothing else like silence.

Sometimes, I would go down to the shore. I remember having fun, everyone doing something; talking, laughing, eating, cooking, fishing. In the evening, we would make a campfire and burn old tires on the shore. Eventually, some parents would start calling their children home, around 7 pm.

When I was down on the shore, my parents could still see me from the top of the tracks when they were home. Sometimes my father would be watching me from the bushes or from the back of the house on the porch off the back of the house. Sometimes I would catch a glimpse of him just watching us from in between the trees. Sometimes the children would yell, Sheila, your father is up there! I got used to the idea that my father was watching me even if I didn't see him, and so I would head home at 7 pm, even if he didn't call me. I knew I should get home before my father came looking for his children.

Next page