Copyright1981 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, Chichester, West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Smith, Bonnie G., 1940-

Ladies of the leisure class.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. WomenFranceHistory19th century.

2. Middle classesFranceHistory19th century.

I. Title.

HQ1613.S54 305.40944 81-47157

ISBN 0-691-05330-8 AACR2

ISBN 0-691-10121-3 (pbk.)

Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Paul Mellon Fund of Princeton University Press

eISBN: 978-0-691-20948-7

R0

Introduction: A World Apart

What is a bourgeois woman? The question first came to mind when I studied history with teachers who described the modern world in terms of class. They used the words bourgeoisie and proletariat, in particular, to define relationships in the productive or market world. Here the question first arose: How was a wealthy woman properly called bourgeois when she spent most of her life at home without any direct connection with either the market or production? In terms of class analysis, what was her place? The problem deepened as I proceeded to look at bourgeois attitudes. Nineteenth-century men were nothing if not industrious, rational, and committed to accumulating capital. But I envisioned the bourgeois woman as someone who probably passed many idle hours, and who was more concerned with spending money than with accumulating it. And if she were rational, why the many depictions of the bourgeois woman as preoccupied with furniture and fashion? I could not jettison accumulated wisdom in a blind defense of her scientific mindset. Outside the classroom came other meanings of the word bourgeois. There were the epithets: oppressors of the people, political swindlers, and the ubiquitous construction of the word bourgeois as synonymous with bad taste. But in no instance did any of these satisfy my craving for a picture of the bourgeois woman. Conventional definitions all applied to men of the bourgeoisie.

There is a way to connect the bourgeois woman with the marketplace world that shaped nineteenth-century history, and historians have made sympathetic efforts to locate her in that environment. They have seen her as the bearer of its children, the consoler of its hard-pressed businessmen, and occasionally as volunteer nurse binding up social wounds through charitable activities. In addition, the clothing with which she adorned herself and the decorative objects she strewed throughout her home contributed to the perpetuation of modern society by softening its increasingly stark contours. The bourgeois woman was also the leading consumer of industrial goods, and, increasingly guided by advertising, she developed a complementary relationship with her male counterpart. While the bourgeois man directed production, she was responsible for the purchase of commodities.

Such an analysis, for all its merit, does not exhaust the substance of bourgeois womens lives, however. It ignores their remoteness from production, and even their explicit dislike for industrial society and its attendant social change. Bourgeois women mistrusted market values and the world beyond the home. Instead of adopting an individualistic, rational, and democratic world view, they abhorred it. Instead of working to amass capital or to contribute to either the economic or political advance of industrial society, they devoted their lives to their families, and, as often, to the Church. Although physically part of an industrial society, bourgeois women neither experienced its way of life nor partook of its mentality. They inhabited and presided over a domestic world that had its own concerns.

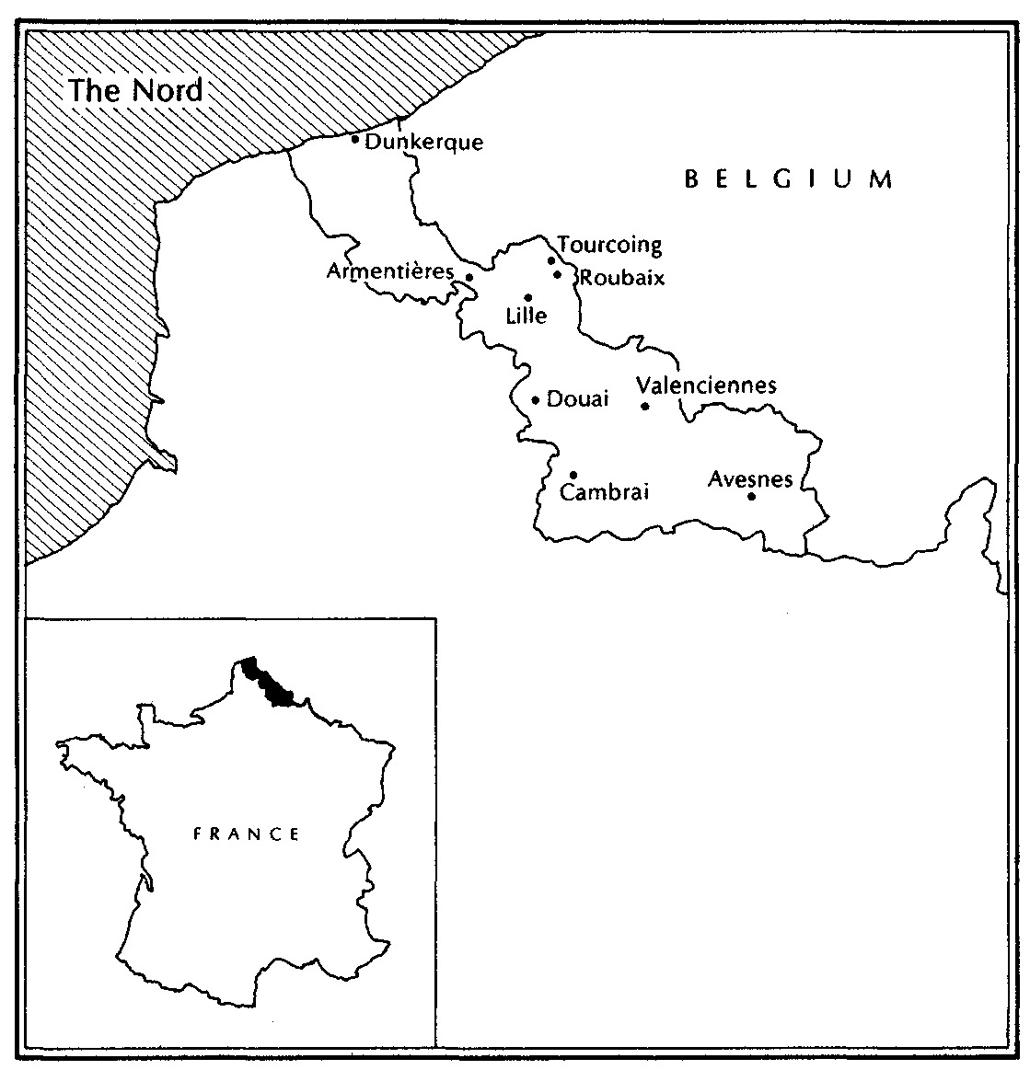

To penetrate this world and its concerns I have chosen as a case study a group of women who lived in the French department of the Nord during the nineteenth century. As wives, sisters, daughters, and mothers of men engaged in the professions or in running businesses and heavy industry, these women constitute a sample of several thousand who could be investigated in terms more or less applicable to bourgeois women in most industrial societies.

To begin, I have looked at the simple, obvious characteristics of their lives. Specifically and primarily, the bourgeois woman of the nineteenth century engaged in reproduction, and her body experienced reproductive cycles more regularly and palpably than did the bodies of men. Menstruation, pregnancy, parturition, lactation, and menopause relentlessly ordered the configuration of female life. It does not require biological determinism to appreciate how deeply rooted in nature womans activity is. Simone de Beauvoir treated this theme minutely in The Second Sex, and it would be foolhardy (especially in a study of French women) to disregard her insights. De Beauvoirs work begins with female biology and leads to an explanation of why men have viewed women as lacking humanity. Along the way she examines the various stages in womens lives as at least partially modulated by their physical fluctuations. It is interesting to connect de Beauvoirs thesis with another pioneering work, Alice Clarks The Working Life of Women in the Seventeenth Century. Clark argued that the home of that era was slowly losing many of its productive functions, and historians hastened to join her in calling the modern home functionless. Others began to look at the psychological workings of the home or at its spiritual nature in an attempt to impute vigor to domestic life. Yet, Clarks depiction linked to de Beauvoirs theory suggests that the home constituted a reproductive arena, an area charged with the content of womens physical lives.

The biological charge to reproduce does not, however, preclude cultural activity. This is the conclusion of Sherry Ortners article that seeks out and locates the cultural activities in the socialization of children. Explicitly building on de Beauvoirs work, she argued that in this capacity women transmitted a civilized tradition, but that the private setting for this activity hid their contribution and perpetuated the affinity of women and nature in mens eyes. Despite an admirable effort, Ortner failed to build on de Beauvoirs insight when she characterized women as merely transmitters of culture, as robots, one might say, in service to the exterior world of male values and standards. Indeed, one might expect a different turn from a feminist anthropologist, for the home remains unexamined, even in a tentative way, as a source of an indigenous and autonomous culture.