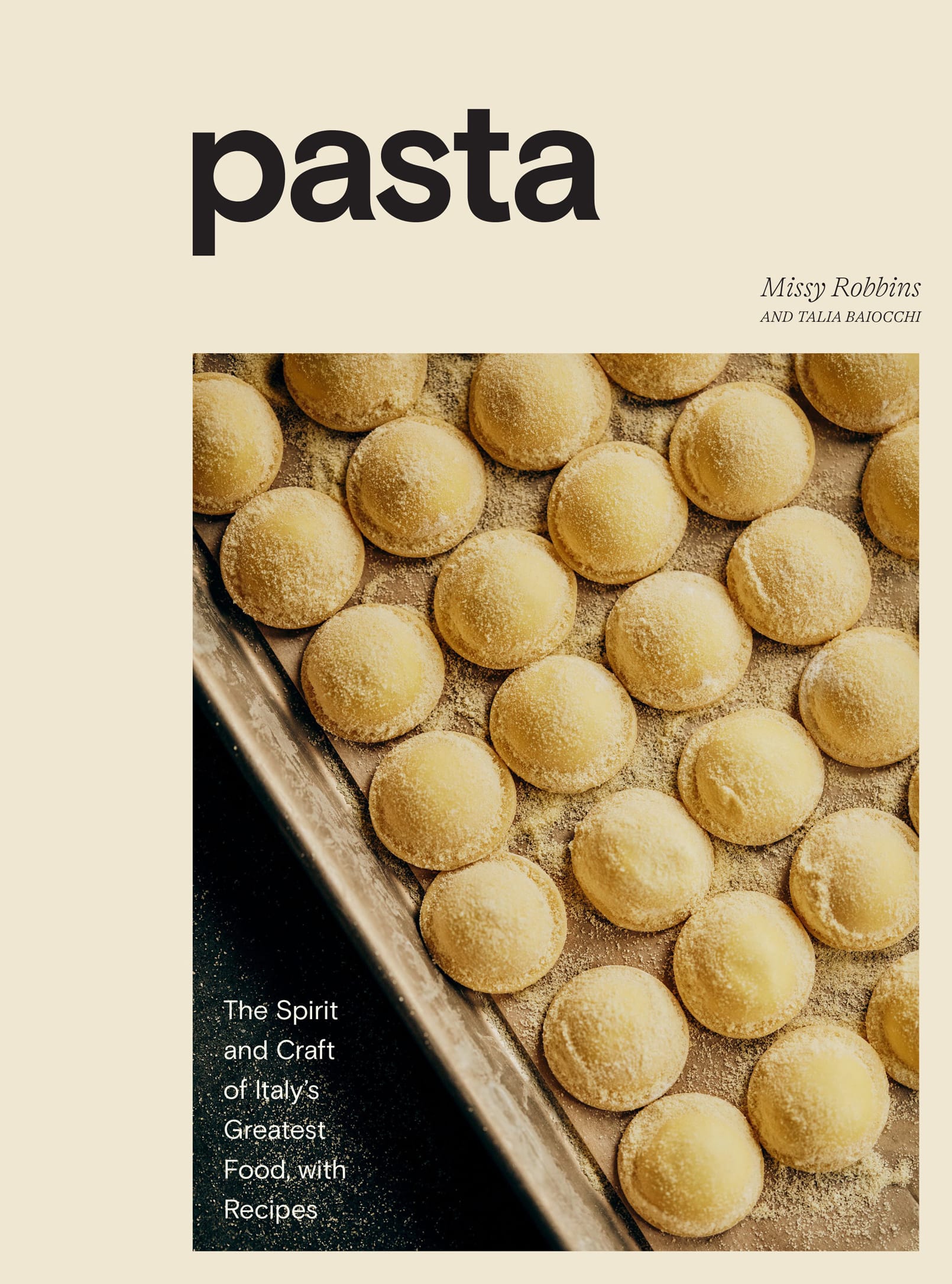

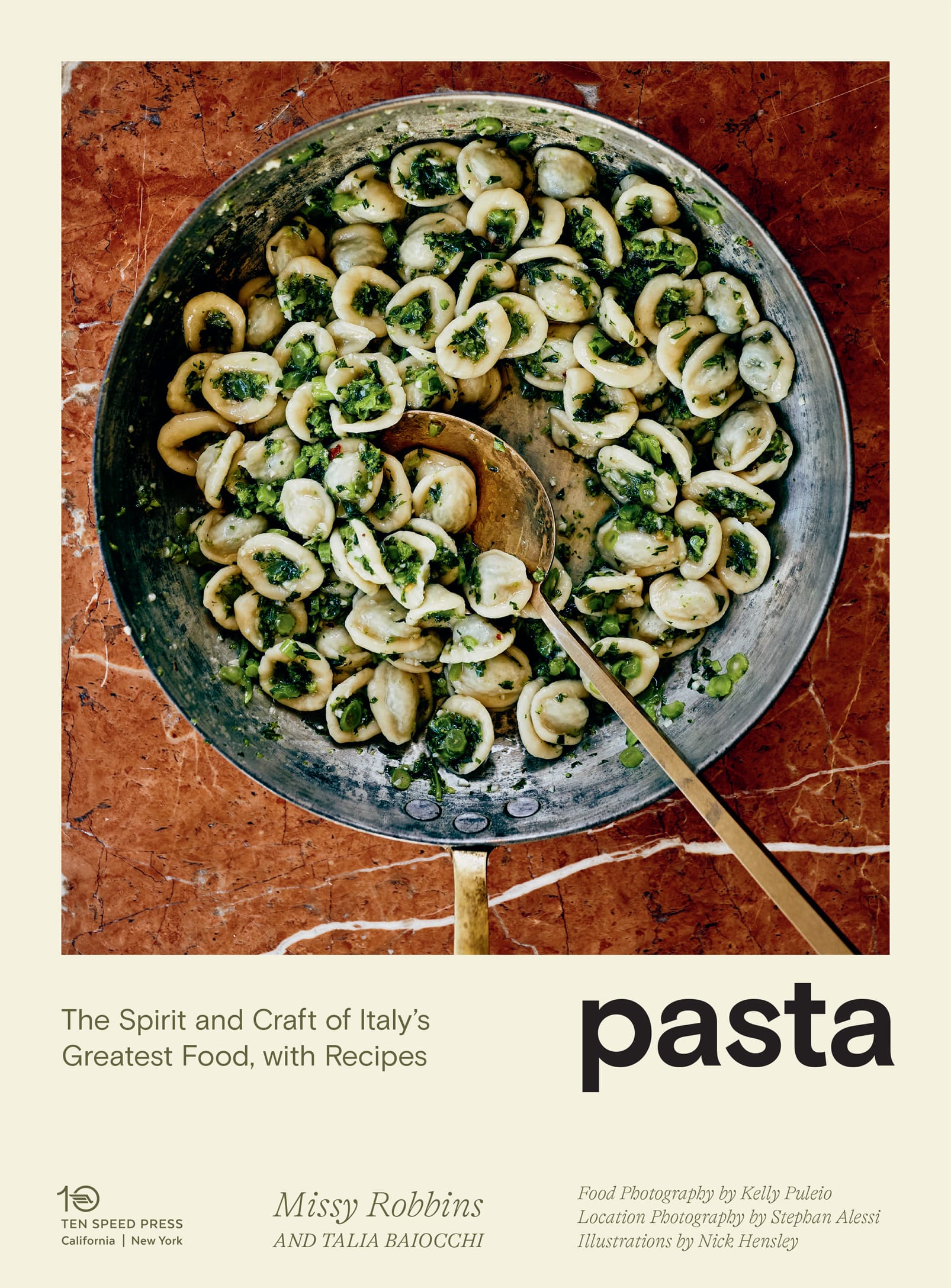

Copyright 2021 by Missy Robbins and Talia Baiocchi

Food photographs copyright 2021 by Kelly Puleio

Italian location photographs copyright 2021 by Stephan Alessi

Illustrations copyright 2021 by Nick Hensley

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

www.tenspeed.com

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the publisher.

LCCN 2021933187

Hardcover ISBN9781984857002

Ebook ISBN9781984857019

Editor: Lorena Jones

Print designer: Elizabeth Allen | Art director: Emma Campion

Print production designers: Mari Gill and Mara Gendell

Print production manager: Jane Chinn

Print prepress color manager: Nick Patton

Culinary shoot producer: Lish Steiling

Culinary shoot assistants: Payson Stultz and Casey Bayer

Prop stylist: Suzie Myers

Recipe tester: Laurie Ellen Pellicano

Copyeditor: Sharon Silva | Proofreaders: Nancy Bailey and Rachel Markowitz

Indexer: Ken DellaPenta

Marketers: Samantha Simon and Stephanie Davis | Publicist: David Hawk

Ebook production manager: Eric Sailer

rhid_prh_5.8.0_c0_r0

Quanto Basta

Pasta making is, at its most basic, an act of humility. Its repetitive, precise manual labora simple gift to the gods of gluten offered up in flour-dusted basements and prep kitchens around the world. It is ceremonious only in its utter lack of ceremony. What has always appealed to me is how the frank marriage of two ingredientswhether flour and water or flour and eggssplinters into hundreds of variations of stuffed, rolled, extruded, dried, stamped, and hand-cut shapes; how each has its own origin story, rhythmic set of motions, and tools; and how mastery can sometimes come down to an elusive sleight of hand: the flick of a wrist, the perfect twist of the index finger away from the thumb. Movements learned only through practice.

In the two years between leaving A Voce in Manhattan and opening my first restaurant, Lilia, in Brooklyn, I spent most of my days at home learning, for the first time since I was a kid, what it meant to cook not for accolades or recognition but for comfort. There was no Michelin. No New York Times. No owners. No need to prove that a Jewish kid from Connecticut with no Italian heritage had any business cooking Italian food. No longer were my thoughts, Is this nice enough? or Is this cool enough? but rather, What kind of food do I want to eat? or What food do I want to cook? and most importantly, Why?

I was cooking pasta that paid homage to Italys iconic regional dishes, sure, but the virtue of craveability was paramount. Its why my food at Lilia and my second restaurant, Misi, is so rooted in home cooking, and its perhaps the only way to explain how a dish as simple as rigatoni with red sauce ended up on Lilias opening menu, and then once again at Misi. I wanted to serve the food that I like to eatthe food Id always been cooking, just stripped down to the studs and rebuilt with a simple mantra in mind: quanto basta.

In Italian cookbooks, quanto basta is typically represented as q.b. It translates to as much as is necessary, and it appears when an ingredient is listed without an exact quantity. Its essentially the Italian version of salt to taste, but it has come to symbolize a shift in focus for meone that places simplicity and comfort first and always makes me ask, Is this really necessary?

It took me decades to get here. This book is meant as a ride-along, from red sauce to regional classics to the pastas Ive made my own. At its core is a journey back to the home regions of some of my favorite pastas in an effort to understand them with new clarityto gain a deeper knowledge of not only how they are faring in a country undergoing constant culinary evolution but also of their sense of place.

Perhaps more than anything, though, this book is my love letter to pasta. What has made pasta the cornerstone of Italian culinary culture for centuries, an indelible part of so many Americans early food memories, and a food so eminently alluring that even the gluten averse cannot resist its siren song is that it asks, first and foremost, something elemental of us: that we enjoy it.

Introduction

My earliest pasta memory was a dish called milk spaghetti, a gooey, unnatural brick-orange tangle of pasta, Campbells tomato soup, Cracker Barrel Cheddar cheese, butter, and milk baked in the oven, cut into squares, and scooped out of a casserole dish with a spatula. It was passed down to my mother from my grandmother Mildred, a woman with a fairly limited stash of culinary provocations.

Needless to say, as a Jewish kid from Connecticut raised in a kosher home, I wasnt exactly reared on carbonara. It was milk spaghetti and, when we went out to our local Italian spots, fettuccine Alfredo, stuffed shells, and the stray cheese-filled ravioli. But my heart belonged to baked ziti. On the weekends, we were regulars at Leons, a real Saturday night kind of place with white tablecloths and those ubiquitous garnet-colored Venetian candles that give so many red-sauce joints their Dick Tracy luster. The ziti, topped with about a pound of mozzarella baked to golden perfection, would come careening through the dining room on giant platters. On weeknights, wed do the same thing at Bimontes, a pizzeria with psych-ward lighting, red-leather booths, and scuffed linoleum floors. Id wash down my ziti with a Foxon Park white birch soda, the local soft drink of choice, while my father tackled a meatball sub and a Pepsi. Wed order a pizza on the side.

By the time I was flirting with adolescence, wed taken to buying fresh pasta at a place called Connies Macaroni, one of many Italian American pastifici in the New Haven area. A jewel box of a shop, it teemed with Italians: mamas picking up red sauce on the way home from Mass; a constant gaggle of older men there only to loiter. Wed load up on linguine and fettuccine.

Eventually, we got around to making our own pasta. By then Id cultivated a fascination, hitching along on my mothers trips to the market just to park myself in the dried goods aisle, obsessively scanning the boxes of pasta to try and commit the shapes and their names to memory. She ended up buying me a pasta extruder when I was elevena white Simac PastaMatic that was nearly impossible to clean. Wed make fettuccine mostly, which wed promptly smother in Alfredo sauce.

This is all to say that there was always pasta. Yet while Id love to be able to draw a straight line from my two beloved childhood red-sauce joints to what I do today, I cannot. Nor can I really suggest that my obsession with pasta shapes or my early forays into extrusion were profound bits of foreshadowing. Instead, my path to pasta has been more about chance than fate.

![Missy Robbins Pasta : The Spirit and Craft of Italys Greatest Food, with Recipes [A Cookbook]](/uploads/posts/book/300525/thumbs/missy-robbins-pasta-the-spirit-and-craft-of.jpg)