The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

1970, 1977 by Paul Friedrich

All rights reserved. Published 1977

Printed in the United States of America

00 99 98 97 96 95 94 93 8 9 10 11 12

ISBN: 0-226-26481-5

LCN: 7789627

ISBN 978-0-226-22693-4 (e-book)

PAUL FRIEDRICH

AGRARIAN REVOLT IN A MEXICAN VILLAGE

With a new Preface and Supplementary Bibliography

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

To Wing and Susi

Contents

Figures

MAPS

PHOTOGRAPHS

GENEALOGIES

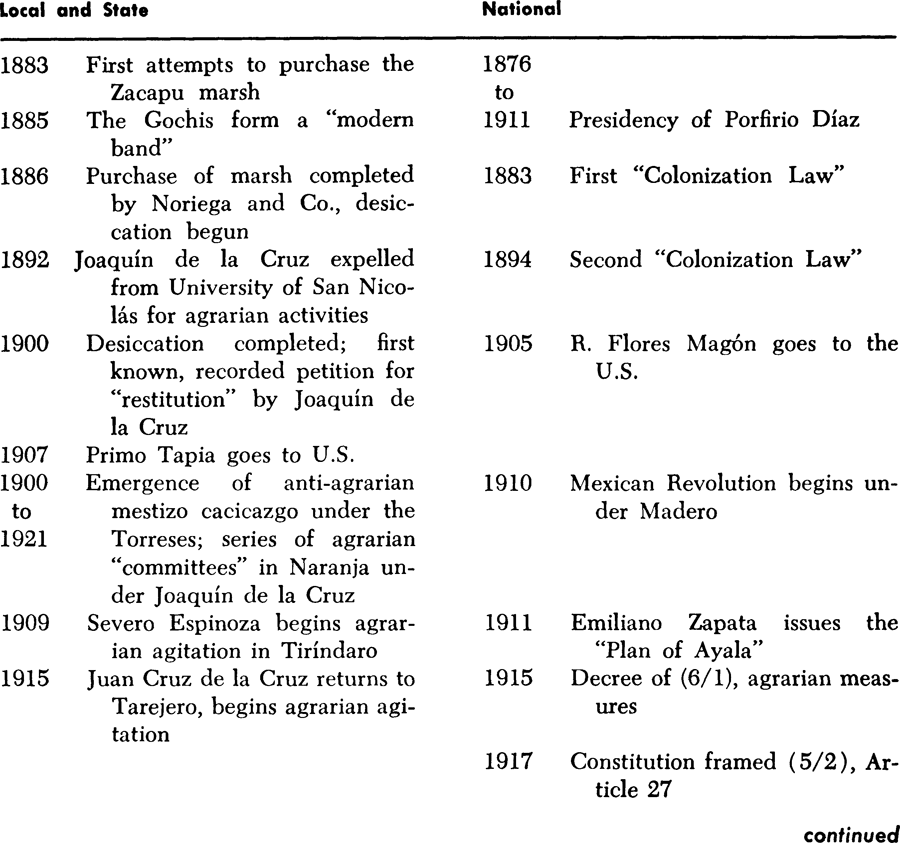

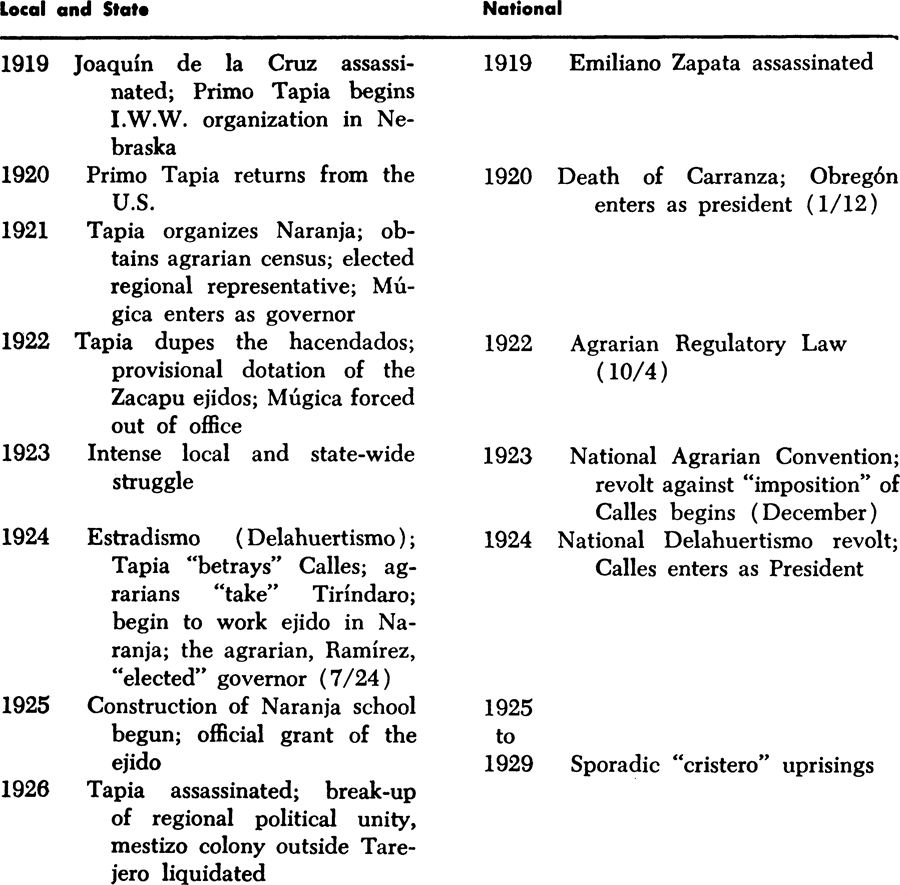

Chronology of Important Events

Preface, 1977

In the years since Agrarian Revolt in a Mexican Village was published, anthropologists have continued to study complex societies such as Mexico or, often enough, the United States. In part this has been due to the accelerated attrition of the cultures of the so-called primitives or to the exclusion of outsiders by new political barriers. But just as much it has been due to the loud presence of social and cultural problems, such as inhuman penal conditions, the destruction of the natural environment, racially and sexually based injustice and perversion, the desensitizing corrosion of the mass media, the loss of civil liberties and of individual integrity, and the threat of modern war with its accompaniment of defoliation, napalm bombing, and mass torture of suspects. An anthropologist who is even marginally aware of these problems may feel some unease or qualms about being pure, aloof and preoccupied (as the Middletons put it long ago) with such in-group, professionalized activities as the study of ceramics, kinship and color nomenclatures, exotic grammars, mythological theory, village harvest rituals, and other arcane albeit commendable pursuits. He may well persist in these pursuits (and I have published or assisted publication in all these areas), but if he doesnt feel some unease, then he is so much the less human.

Among the problems which besiege us, agrarian inequity, injustice, revolt, and reform loom large indeed. This is glaringly true of the United States, where every year hundreds of thousands of farm people are driven into the cities from their small land holdings through the operations of local power holders and the huge development corporations; agrarian reform is one of the major (and rarely mentioned) needs of our country today.

In Latin America the past decade has witnessed an intensification of agrarian stress which has not and never will be silenced by the military squads of Peru and Chile, the tortures of the Brazilian police, or other, similar methods. Within this Latin American context it is perhaps Mexico that stands out most today because of a forceful combination of recent circumstances. First, the population, which is still mainly rural, has continued to grow explosively, to over fifty million people today compared with less than half that three decades ago. Second, the recent Echeverra presidency variously supported, encouraged, or at least condoned the land claims and land seizures of peasants, thus stimulating widespread unrest: in one case in Sinaloa and Sonora in 1977 about ten thousand peasants were involved in the forceful occupation of lands. Third, the powers of big industry, the large landlords, the local caciques, and diverse conservative elements have been moving against the restless peasants, sometimes with violence; in the 1950s and 1960s peasant leaders who were similar in some respects to the ones depicted in this book were assassinated for political reasons. Today one third of the Mexican work force is unemployed and the land per capita ratios are edging toward the dangerous levels that preceded the Mexican Revolution.

The past decade has seen the agrarian problems of Mexico and of the world at large become more anguished and demanding of our attention than they were when this book was first published, so that by the logic of history it has become more rather than less relevant, younger rather than older.

Preface

Agrarian Revolt is about the origin and growth of agrarian reform and agrarian politics, the formation of an agrarian ideology and of the techniques of agrarian revolt, and the lives of real persons in their relation to state politics. A series of unique historical events and of interactions between individuals, groups, and pueblos, is related to certain generalizations about agrarian revolt and politics. On the one hand, this book describes forty years in the agrarian history of a small pueblo; on the other, it aspires to more universal import by raising questions about local politics and agrarian reform that pertain to hundreds of millions of peasants on many continents.

A brief preview of the chapters that follow is clearly in order. The first presents the background of Naranja, a village located in the state of Michoacn in southwestern Mexico. The local culture of the end of the last century was reconstructed by combining several ethnological methods: interviews with older natives, internal analysis of the contemporary system, comparison with other Tarascan pueblos, and so forth. Most of my time was spent in Naranja, where I discussed the facts of culture and politics with many persons. But I managed to visit thirty-two other Tarascan communities, including Tarecuato and Chern, and did two weeks of field work in Tarejero and Azajo. The historical description in this first chapter corresponds to what, in a more adequate analysis, would be a statement of the cultural symbols, most of them signalled by words or fixed idioms in Tarascan. Part of my purpose here has been to immerse the reader in this pre-agrarian world so that he can appreciate more fully the tremendous thrust of the subsequent agrarian revolt.

The second chapter is an historical sketch of the economic and social changes within the village as it was affected from without between 1885 and 1920. Great significance has been attached to the seizure of the extensive marshlands by Spanish entrepreneurs, and the subsequent conversion of the entire region into landed estates producing cash crops for the national economy. The chapter is based on interviews, and government records in the Agrarian Department in Mexico City.

The third chapter considers the complex personality of the agrarian hero Primo Tapia, who is studied in detail because he plays a central role in regional political history, and because he illustrates a little understood but politically important type of this century: the local or regional revolutionary leader in an underdeveloped area.

In the last chapter I analyze the initiation and successful completion of agrarian revolt in Naranja and in the neighboring villages between 19201926. Some of the information in this and the preceding chapter was obtained from historical documents, some from archives in Mexico City, and some from political migrants living in that city; the biography by Martnez contains, intermittently, some facts about Tapia, and important documents: his dreams, letters, and the manifesto. But the bulk of my information was secured through interviews with older villagers in the Zacapu valley, many of whom have since passed away. To a considerable extent, the problems of organizing an agrarian revolt and the experience of such a revolt are depicted from a hypothetical point of view: that of the revolutionary leader Primo Tapia.