Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic

reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear

as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged

to experiment with user settings for optimum results.

Copyright 2014 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Unless otherwise noted, photographs are from the authors collection.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Van Willigen, John.

Kentuckys cookbook heritage: two hundred years of southern cuisine and culture / John van Willigen.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8131-4689-8 (hbk. : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-8131-4691-1 (pdf)

ISBN 978-0-8131-4690-4 (epub)

1. Cooking, AmericanSouthern style. 2. CookingKentuckyHistory. 3. CookbooksKentuckyHistory-19th century. 4. CookbooksKentucky Bibliography. I. Title.

TX715.2.S68V38 2014

641.59769dc23

2014016214

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

Introduction

Cookbooks as the Key to Kentucky Foodways

and Culinary History

Kentucky cookbooks (that is, collections of recipes produced by Kentucky authors or groups) provide a glimpse of what Kentuckians ate, how they prepared food, the cooking technology used, and the social setting of food preparation and consumption at the time of the books compilation. Tapping into this potential resource requires careful analytical reading, however. As John Egerton notes, Cookbooks tend to keep their social and cultural clues discreetly buried between the lines, but when they can be uncovered they may be useful barometers of a societys tastes and priorities and values (1993, 17). This book is based on a close reading of a selection of Kentucky-published cookbooks from the past and the present.

It is clear that cookbooks and their recipes have changed considerably in terms of diversity and format. The first noticeable change is that the rate of publication has increased over time. There were few nineteenth- century cookbooks, although this started to change after the Civil War. During World War I, the Depression, and World War II, few cookbooks were produced. By the 1950s, there was a large increase in the number of cookbooks published, followed by another substantial surge starting in the 1980s. More recent increases reflect readers growing interest in food writing, which is associated with changes in the style and content of cookbooks. These changes are the result of many factors, including the development of new dishes, evolving recipe formats, new food preparation technology, shifting availability of ingredients, increased presence of branded or processed foods, growing interest in saving time when cooking, new knowledge about cooking techniques, greater cultural diversity in Kentucky communities, and changes in the meaning and politics of food.

Many of the changes in cookbooks and their recipes can best be understood in terms of the transformations occurring in the American food system. The two overarching changes are that consumers are less involved in producing food and that food must travel a longer distance. Using the idea of a watershed as a metaphor, culinary historian Ann Vileisis (2008) speaks of the foodshed, or the area from which we obtain our food. In the 175 years covered by this book, the limits of the foodshed have changed for many Kentuckiansfrom the garden spot near the house, adjacent fields and pastures, and the cellar to faraway and largely unknown locations. This has had important consequences. People now have less knowledge about where their food comes from, how it is produced, who the producers are, and whether it is wholesome and safe to eat. A major part of our culture has been taken from us. One of the consequences is a loss of knowledge and skill. One might say that, in certain realms, we have been decultured. At the same time, we have obtained new food knowledge. I may not know how to slaughter and dress a chicken, but I have a working knowledge of nutrition and I can prepare a credible pad Thai. Some argue that our interest in cookbooks is related to our separation from food production.

It is not often a cookbooks goal to depict or explain history, but in the process of providing lists of ingredients and instructions for cooking them, it may reveal traces of history. Further, it is interesting to place cookbooks in their social context and to think about how they reflect their times. Often this is quite obvious in the recipes, but it may require a careful reading, rereading, and interpretation. When I originally conceived of this book, I thought in terms of excavating an archaeological site. Cook-books are like archaeological strata. Each one reflects something of the era in which it was created. It does not provide a complete picture of what life was like; rather, it offers a complex and hard-to-fathom tracing of reality as it existed for its creator. When archaeologists excavate a site, they may not find much to work with, and they are often hard-pressed to understand the meaning of the artifacts they do uncover. So it is with cookbooks: although much can be learned through the study of cookbooks and their recipes, they are of limited use for understanding foodways.

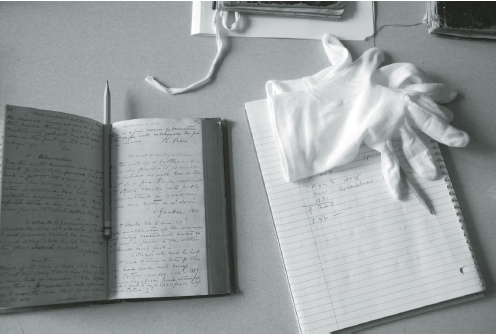

Working with Liberty Halls early-nineteenth-century manuscript cookbook. (John van Willigen)

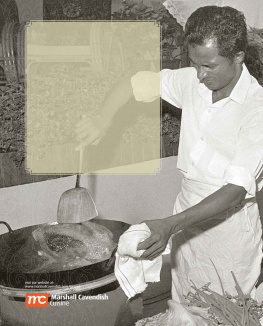

One limitation is the problem of historical lag. With regard to using cookbooks and recipes to study culinary history, Karen Hess notes, The lag between practice and the printed word is one of the most frustrating aspects of work in the discipline of culinary history (Hess 1992, 44). Hess goes on to cite the example of johnnycake and other corn-based, hearth-baked breads of the early colonial era, noting that 175 years elapsed between the earliest preparation of these foods by American cooks and the recipes appearance in the historical record. This is not to say that these recipes did not exist, but they were most likely kept in peoples heads or sometimes written out by hand. In fact, most recipes are not written; they are stored deep in memory or improvised, based on the cooks creative vision and knowledge of the fundamentals of cooking, as well as what is in the pantry. A lot of cooking is done by ear, to use Marion Flexners phrase describing the method of the African American cooks who worked for her family (Flexner 1941, x). Those wonderful cooks internalized the principles of preparation that produced the results they were interested in. So while there might be a recipe, it is probably not written down and perhaps not even memorized: it just is.