The team of cheesemakers at Westcombe Dairy.

One of the finest views in all of Wales: the Snowdonia National Park where, nestled within the mountains, lies the dairy where Carrie makes her Brefu Bach.

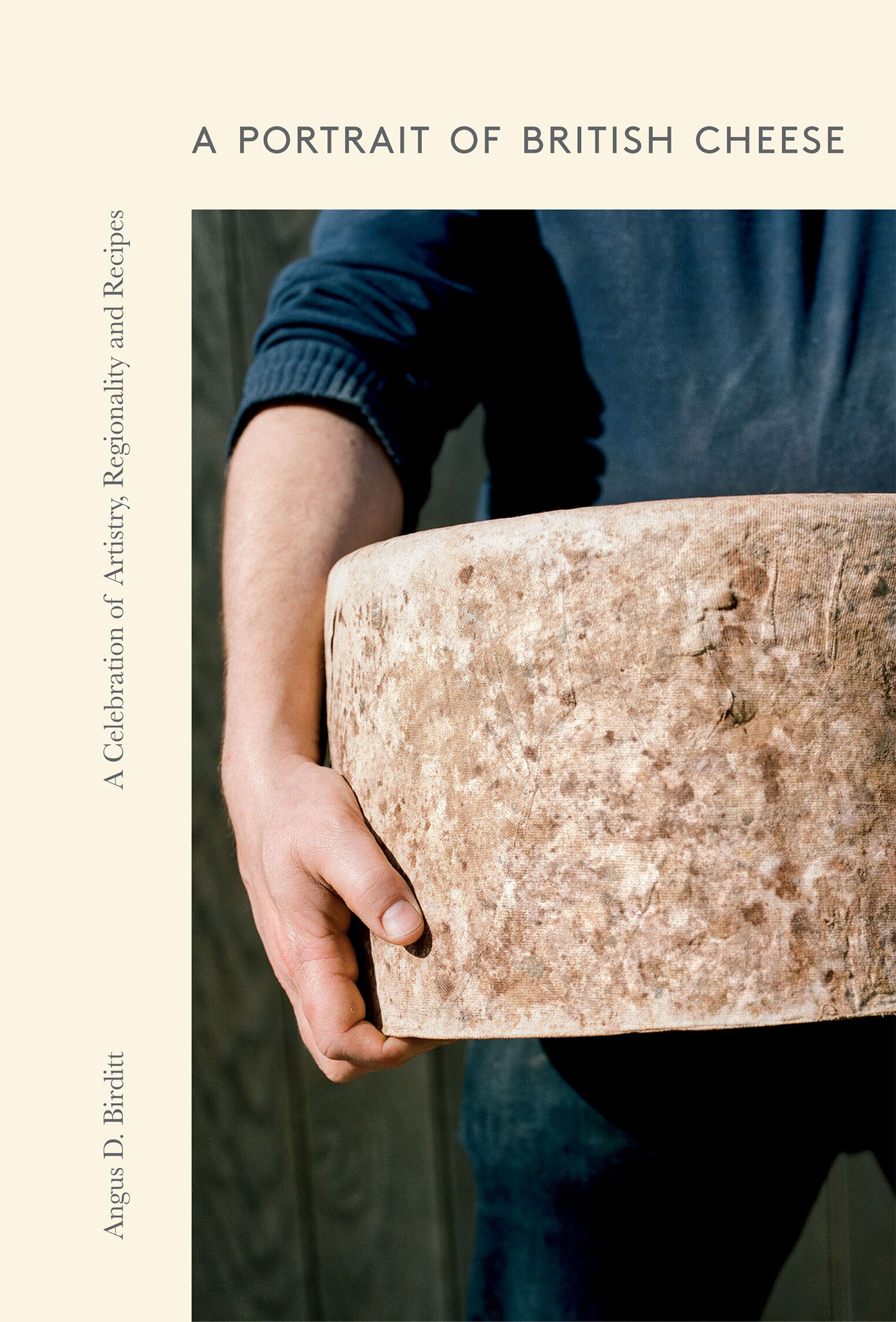

Gary Gray has made Applebys Cheshire for over thirty years at Hawkstone Abbey Farm in Shropshire.

Can there be anything more blissful than savouring a sizeable chunk of artisan cheese, one that has been made lovingly by hand using traditional methods and with completely natural, full-fat creamy milk from happy cows that have grazed on diverse pasture? Sampling cheese is often seen as a refined pastime, to be conducted in an appropriate setting but for me, to make the most of it, I prefer to pick a spot somewhere deep within the countryside, on a riverbank or in a meadow, underneath an oak or willow tree and watch any wildlife that happens to pass by. All thats needed is a slice of fresh bread or a cracker, smothered in a thick layer of salted butter, with the cheese placed carefully on top.

The monumental sight of thousands of cheeses stacked high in the maturing rooms at Ulceby Grange Farm in Lincolnshire, where they splash water on the floor to maintain humidity and the correct temperature.

I try to replicate this experience whenever possible, and when I do, I find that everything around me stops. My mind and body are soaking in the rural setting while my taste buds drown in cheesy euphoria.

For as long as I can remember, cheese has been a rich source of pleasure and indulgence, fully endorsed by my mother, who regarded it as a sort of elixir of life: Did you know that your great-grandmother Eva enjoyed a large slice of Irish blue cheese and a half pint of stout every night for her tea, and she lived until she was ninety-four years old! So, of course, hearing that, I just assumed it was in my blood to eat copious amounts of the stuff and that it would do me nothing but good.

However prevalent cheese may have been on our family table, it was never there for very long and, being the youngest of three brothers, I invariably had to fight for it. Picture three boys at suppertime in our small nook of a kitchen, tussling over the grater, the last sliver of Parmesan, and a huge mound of steaming spaghetti, which all needed to be portioned equally to prevent all-out war from erupting. Often it did, ignited by one brother taking one too many sprinklings of grated cheese and with the other two fuming in righteous indignation at the unfairness of it.

Growing up in the Cambridgeshire countryside, I spent most days exploring the surrounding fields with my head full of dreams and make-believe, and always fuelled by some sort of cheese. As my teens turned into my twenties, my adventures grew longer and evolved from fantasy into fact-finding and quiet observation, and always with a cheese sandwich of some sort to keep me going. Guided by my trusty copy of Richard Mabeys Food for Free, I could now augment my cheese sandwiches with fresh sprigs of wild garlic or bitter dandelion.

After university, I moved to Wales, swapping the vast arable fields and open skies of East Anglia for steep mountains and long winding rivers with kingfishers, dippers and otters, and along the banks, grazing happily, cows and sheep all rarely seen in Cambridgeshire. The cheeses changed too. After devouring Suffolk classics and Norfolk staples, I was now peeling the wax off Welsh Black Bombers, sampling Snowdonian .

It has got to the point, since researching this book, that I now feel a little lost on a walk if my bag isnt weighed down with a hefty ration of cheese. To make the most of any expedition, whether pleasure- or work-related, I now try to plan my journey via a village with a shop or, better still, a cheesemonger where I can stop and indulge my dairy addiction.

Wherever I am in the countryside, I always try to connect with the land, whether by learning about the history of a particular place, identifying the local flora and fauna or by following the seasons each bringing a bounty of different wild foods or simply trying to raise awareness about the natural world and all its wonders.

Over the years, I have discovered that the best way to learn about such things is to find the people whose lives are deeply interwoven with the natural environment, whose knowledge and skills are perfectly adapted to its cycles, who know how to value its wildlife, harness its elements or harvest the plenty of its soil and coastline. And if the harvest is mouth-wateringly good, well, I am all the keener to learn!

My enthusiasm to learn from such individuals has led me all over the British Isles, from catching eels and crayfish under the open skies of East Anglia with the last traditional eel fisherman in the country, to foraging for dodgy-looking mushrooms in the rainforests of Snowdonia with the unofficial master of fungi. But it was the artisan cheesemaker whose quiet sense of belonging and intimate relationship with the natural environment that fascinated me the most. Maybe it was their savoury, unctuous creations that tipped the balance, but with each cheesemaker I met, I delved further and further into the extraordinarily complex and varied world of artisan cheese the product of a magical symbiosis between land, livestock and producer.

If you came to me at the start of writing this book a couple of years ago, you would find me just touching the surface of artisan cheese skimming the milk, if you will! Looking back, I had absolutely no idea how much I would learn about it; now it is a subject about which it seems I can never learn enough. But as I have travelled to what seems like every corner of the British Isles clocking up thousands of miles in my old midnight-blue Saab estate packed full of cameras, raincoats, wellies, hats, shorts, books, a pair of binoculars, an old wooden wine box full of apples, beetroot juice and half-nibbled cheeses to keep me going, and regularly dragging around my other half, Lilly, or my mother, Serena to meet the best makers in the business, nagging them to tell me everything they know, I have become spellbound by the range and complexity of British artisan cheese. It is a marvel of our isles, and one that I would like to share with you all.

The exact origin of my love of artisan cheese, besides that of my blue-cheese-loving great-grandmother, is rather blurred the downside of having a useless memory! But what I do remember are certain events that had me swimming in dairy delight. One of my first memories is of summer holidays with my family in North Norfolk, where we would walk through the countryside and along the sweeping sands of Holkham Bay and Burnham Overy Staithe. On every walk we would stop for a picnic, laid out by my mother on a green and blue tartan blanket, which would always include a hefty slice of cheese, several baguettes and wafer-thin layers of Wiltshire ham, all masterfully constructed into sandwiches with the aid of her miniature Swiss army knife.

Another, perhaps less nostalgic, memory was of my time at university when Lilly and I worked part-time as waiters at one of the Oxford colleges. For several nights of the week, we would serve the dinner guests the dons, fellows, guest speakers and lucky students. Each person would be served a three-course meal, and each table a crate of red, white and dessert wines, followed by a vast platter of cheese. The wine was demolished, of course, but more often than not, the cheese was never touched. So, at the end of each meal, when the guests had left, the leftover cheese was at our disposal I will be forever grateful to Karl, the catering manager, for our weekly cornucopia of free cheese. Taking full advantage, we wrapped in baking parchment as much cheese as we could hold in our hands and balance on our bikes. Thick, melting slices of British blue and semi-soft cheeses, alongside plenty of French varieties, from Comt to Reblochon, were devoured in the wee hours of the morning, vital fuel to power us through the next days lectures.

The team of cheesemakers at Westcombe Dairy.

The team of cheesemakers at Westcombe Dairy.  One of the finest views in all of Wales: the Snowdonia National Park where, nestled within the mountains, lies the dairy where Carrie makes her Brefu Bach.

One of the finest views in all of Wales: the Snowdonia National Park where, nestled within the mountains, lies the dairy where Carrie makes her Brefu Bach.  Gary Gray has made Applebys Cheshire for over thirty years at Hawkstone Abbey Farm in Shropshire.

Gary Gray has made Applebys Cheshire for over thirty years at Hawkstone Abbey Farm in Shropshire.  The monumental sight of thousands of cheeses stacked high in the maturing rooms at Ulceby Grange Farm in Lincolnshire, where they splash water on the floor to maintain humidity and the correct temperature.

The monumental sight of thousands of cheeses stacked high in the maturing rooms at Ulceby Grange Farm in Lincolnshire, where they splash water on the floor to maintain humidity and the correct temperature.