A Western Journal

A Daily Log

of

The Great Parks Trip

June 20July 2 , 1938

by

THOMAS WOLFE

1951

UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH PRESS

Copyright, 1951, by Edward C. Aswell,

Administrator, C.T.A. of the Estate of Thomas Wolfe

Note on

A Western Journal

By Edward C. Aswell

(From the Virginia Quarterly Review, Summer 1939)

When Thomas Wolfe went to the Pacific Northwest in the early summer of 1938, he was impelled by a combination of strong motives. He had just delivered to his publishers a manuscript of twelve hundred thousand words. He was tired and wanted a rest. The Pacific Northwest was the only part of the United States he had never visited. Finally, he had never lost his small boys sense of wonder and he wanted to ride on a streamlined train.

When he arrived in Portland, Oregon, he met two newspaper men who were planning a trip by automobile through all the National Parks of the Far West. They invited Wolfe, who could not drive a car himself, to go with them. He was always avid to learn all he could about his America, and he could get as drunk on new geography as on strong liquor. So, his great weariness momentarily forgotten, he accompanied his two new friends.

On July 4, 1938, the trip was over and Wolfe was in Seattle. On that day he wrote me a letter in which, for the first and only time, he spoke of A Western Journey:

I am feeling much better already, although I have traveled ten

thousand miles, five thousand in the last two weeks, and seen

hundreds of new places and people. My fingers are itching to

write again. I have already made fifty thousand words of notes on

this journey. I propose to stay here a couple of weeks longer and

get these notes revised, rounded out, and typed in a more

complete form. The whole record I am calling simply A Western

Journey It is really a kind of tremendous kaleidoscope that I

hope may succeed in recording a whole hemisphere of life and of

America.

This was part of the last letter I was ever to receive from Wolfe. Two days later he had pneumonia, from the complications of which he was to die in Johns Hopkins Hospital within nine weeks.

There in Baltimore, on that sad September fifteenth, a few hours after Wolfe had died, I sat in the hospital talking with the members of his family. The question of his unpublished manuscripts came up. I asked if they knew anything about A Western Journey. His mother undertook to look through his bags. And there it was a bound ledger of the kind used in simple bookkeeping; it was in just such ledgers as this that Wolfe had written his first longhand drafts of everything. The ledger was full to the last page of his almost illegible penciled scrawl, with the title, A Western Journey, at the beginning. There were not fifty thousand words, nothing like it. Wolfe always used round numbers loosely. When he said, I have written a million words, he meant: I have written a lot. When he said, I have written fifty thousand words, he meant: I have written only a little; in fact, I have just started. It was the last manuscript which that large hand of the artist would ever write.

Notes on

A Western Journal

By the University of Pittsburgh Press

The University of Pittsburgh Press, in January 1950, entered into a contract with Edward C. Aswell (Administrator, C.T.A. for the estate of Thomas Wolfe) to publish Wolfes Western Journal.

This last writing of Thomas Wolfes had been brought to the attention of the Press by Lawrence Lee, associate professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh, who had published a fragment of the Journal in the summer issue, 1939, of the Virginia Quarterly Review when he was editor of the Review.

From the Houghton Library, Harvard University, the Press got photostats of the Journal as it was written in the almost undecipherable handwriting of the author.

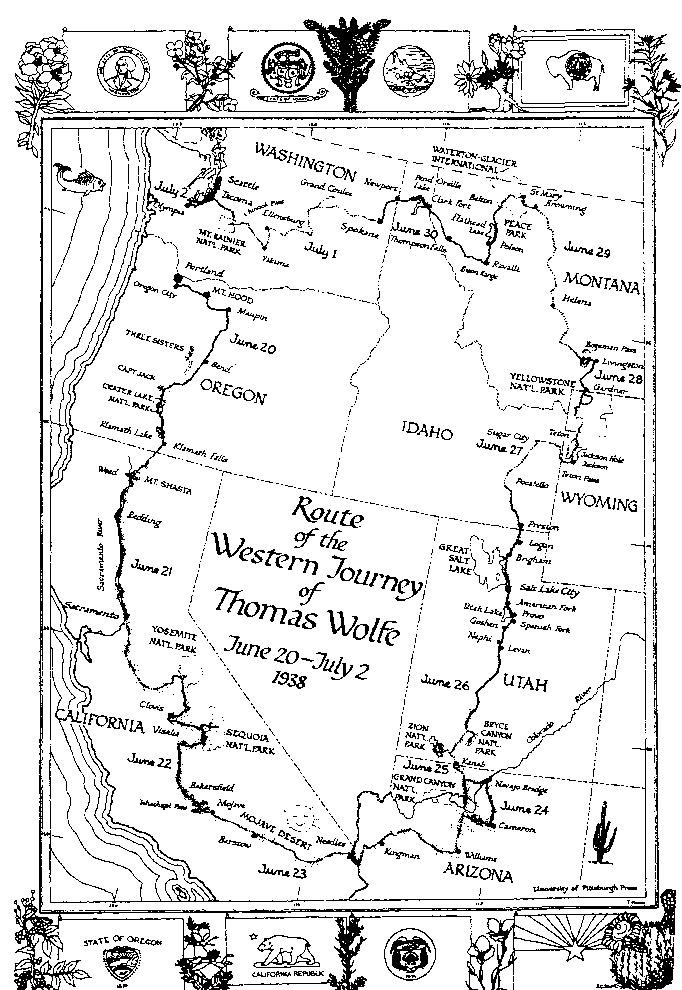

The Journal was kept daily from June 20 through July 2, 1938, while Wolfe was on a motor trip through national parks of eight western states. It was written with a soft pencil, late at night, after the long trip of the day was over, on the pages of a record book (National 1759 1/2). In the book are 300 lined pages, x 8 5/8, with one-inch margins marked off in red. Record is impressed in the middle of the front cover, and the book shows much wear.

For a few pages in the beginning of the book (19) Wolfe wrote on both left- and right-hand pages. From 9 through 215 he wrote on right-hand pages (except for 150, which is a page of figures); from 215 on through to 300 he wrote on all pages, both left- and right-hand. The sequence of the account of his journey, day after day, however, is not always to be read in the order of numbered pages. The account in sequence is to be read on both left- and right-hand pages through to 299, and then back on the left-hand pages (the even numbered pages) from 300 to 238. In spite of the Journal's turning back on itself as Wolfe wrote it, the calendar sequence from Monday June 20 through Saturday July 2 helps make clear the order and sequence of his writing.

Another confusion results from the writing on pages 4, 6, and the bottom of page 8. These fragments dated June 31, Spokane, are written among the records of June 20 and 21, on pages and in territory Wolfe had left behind many days before he reached Spokane. It seems probable they were written after the trip was over and after Wolfe had written on page 238 End of the Trip. In the first place, there is, of course, no June 31 in the calendar and there are accounts of June 30 and July 1 in the Journal where they belong. In the second place, the substance of these fragments dated June 31 is a kind of summary of impressions and reflections on the whole trip. For these reasons, the pages 4, 6, and the bottom part of 8 are printed at the end of the Journal. In any sense, actual or artistic, the final words on 8 are a more satisfying climax for the Journal than those on 238.

The Journal is almost never written in complete sentences. It is a series of phrases, even stray words, usually separated one from another by dashes. The ands which follow almost every dash or introduce any new impression seem not to be connectives but rather response to the rolling of the white Ford and to the tumbling eagerness of Wolfe's thoughts and feelings. It is as if always his mind ran faster than his pencil could.

The punctuation, the capitalization and the paragraphing used in this book are Wolfe's. The spelling, because of the uncertainty about some letters and the shorthand method Wolfe often used, may be edited.

Where Wolfe himself used a question mark to show uncertainty about the names of towns, mountains, rivers, or the like, the map was consulted and the right name is given in notes at the end of the book, on page 71. The faithfulness with which Wolfe has recalled and recorded every turn in the road makes it not too difficult to trace on the map the very roads the white Ford traveled.

The Journal is printed here in full and, we believe, just as it was written. To decipher every word and try to be sure it was the word Wolfe wrote was the pleasant labor of many hours with my colleague, Percival Hunt. His unflagging zeal and inspired sleuthing is responsible for discovering many words that might have remained forever a mystery. For both of us, I think, the very

difficulties have made the authors tremendous intensity, his eagerness, intolerance, gentleness, and elemental poetry a very real Itselfness (as Wolfe might say)an Itselfness which is there to enjoy, apart from any literary form, or lack of it, and apart from any agreement with the authors opinions.