Missionary Children, Bicultural Identity, and U.S. Colonialism in the Pacific

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover artwork engraved by S. S. Jocelyn after a sketch by William Ellis [public domain], courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Portions of chapter 1 previously appeared in Birthing Empire: Economies of Childrearing and the Formation of American Colonialism in Hawaii, Diplomatic History 38, no. 5 (November 2014): 895925. Published by Oxford University Press.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

This project would not have been possible without the full encouragement and support of the University of NebraskaLincoln Department of History. Research and travel grants provided by the department allowed me to travel to Honolulu and New England to conduct extensive archival research. I would like to especially thank James LeSueur, Margaret Jacobs, Lloyd Ambrosius, and Loukia Sarroub for their commitment to this project. Most importantly, I thank Tim Borstelmann, my graduate adviser and friend, whose teaching made me a better student, scholar, and writer.

Additional research was made possible by the National Endowment for the Humanities and American Historical Associations Bridging Cultures at Community Colleges Initiative: American History, Atlantic and Pacific Project. I would like to thank Jim Grossman, Philip Morgan, Bill Deverell, Tom Osborne, Dana Schaffer, and Cheryll Ann Cody for their personal efforts in support of the Bridging Cultures project.

Numerous institutions and archival specialists also helped me prepare this manuscript. I would like to thank those at the Hawaiian Mission Childrens Society, Cooke Library, Harvard University, Williams College, Mt. Holyoke College, Huntington Library, and Library of Congress for their kind and thoughtful aid. Special thanks I give to Carole White, John C. Barker, Kylee Omo, Sara Lloyd, Patricia Albright, Linda Hall, Carrie Hintz, Ben Brick, and Kathy Walter. I also thank Anne Foster, Ted Melillo, the late Jennifer Fish Kashay, Gary Okihiro, Hugh Morrison, Mary Clare Martin, Karen Sanchez-Eppler, Geri Shomo, Andrew Graybill, and Cari Costanzo Kapur, as well as the anonymous peer reviewers, who gave the generous gift of their time in reading various drafts of the project or answering specific research questions.

Early encouragers of this project also included the Society for the Historians of American Foreign Relations and the Society for the History of Childhood and Youth. I thank their journals for allowing me to reprint portions of published work within this book.

I am extremely grateful to the University of Nebraska Press and my editor, Bridget Barry. Bridgets enthusiasm for the book and efforts on my behalf have made the lengthy process of editing and publication more than worth it. I also thank Jane Curran for providing her wonderful copyediting skills.

Finally I acknowledge my husband, Marc, and daughters, Sophia and Penelope, for their unwavering support. I am always grateful for you.

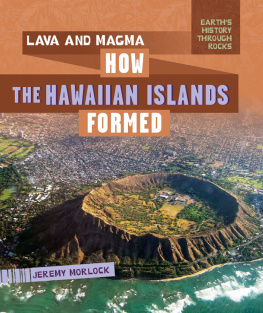

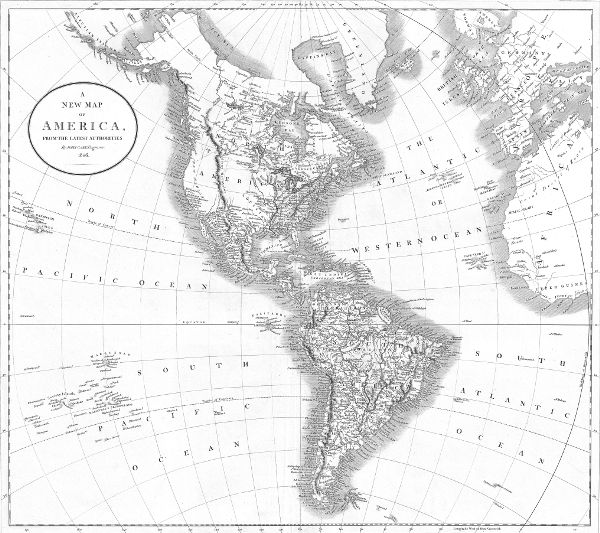

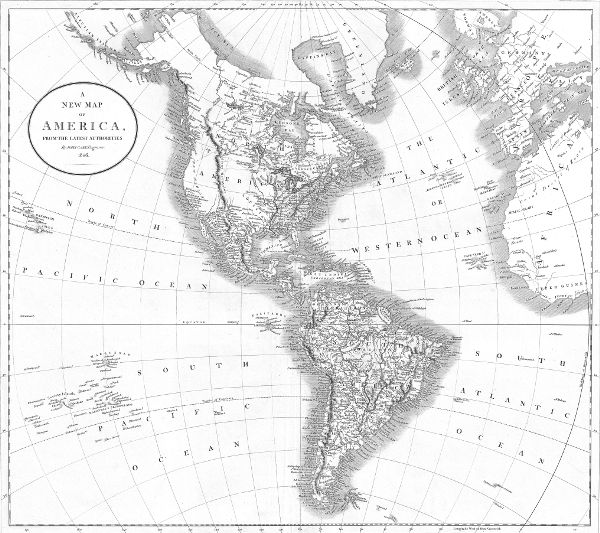

Travel from New England to the Hawaiian Islands in 1819 required a six-month journey by sea around South America. Contemporary travel accounts, such as this 1806 map of the Western Hemisphere by English cartographer John Cary (17541835), would have demonstrated to the American missionaries the enormity of their decision. Missionary children, unlike their parents, centered their world in the Pacific Ocean. From John Cary, Carys New Universal Atlas, containing distinct maps of all the principal states and kingdoms throughout the World. From the latest and best authorities extant (London: Printed for J. Cary, Engraver and Map-seller, No. 181, near Norfolk Street, Strand, 1808). Wikimedia Commons.

Imperial Children and Empire Formation in the Nineteenth Century

Kauhua Ku, ka Lani, i-loli ka moku; Hookohi ke kua-koko o ka Lani; He kua-koko, pu-koko i ka honua; He kua-koko kapu no ka Lani. (Big with child is the Princess Ku; the whole island suffers her whimsies; the pangs of labor are on her; labor that stains the land with blood.)

Ancient Hawaiian mele

In 1819, when passenger travel across the Pacific Ocean was unfathomable to most Americans, seven couples and five children left New England and made the nearly six-month sea voyage around Cape Horn to the Hawaiian Islands, arriving in 1820. The young missionaries left behind their worldly possessions but took with them the prayers and financial support of the newly established American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions ( ABCFM ). The missionaries were soon joined by others. Between 1819 and 1848 the ABCFM launched roughly 150 missionaries across the Pacific Ocean to the Hawaiian Islands. As the first U.S. missionary organization with an international agenda, the ABCFM hoped to evangelize the small, independent island kingdom according to Congregational and Presbyterian theology.

Domestic concerns became political ones, and the American missionaries began to rationalize policies transferring land and political power to their control.

In fact, the number of white children born in the Hawaiian Islands influenced more than missionary policy. Children did not retain their missionary parents qualms about using the Hawaiian land for material benefit or shaping the islands into what they termed an Anglo-Hawaiian society. In reality the essence of their childhoods had groomed them for little else. Through parental neglect, as well as their parents imperfect attempts to racially segregate them, the children developed an aggressive independence that tended to question both parental and native authority. In the process the children cultivated a deep possessiveness over Hawaiian lands, which culminated in their revolt against the Hawaiian monarchy at the end of the nineteenth century.