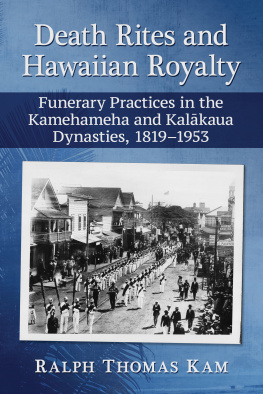

Death Rites and Hawaiian Royalty

Funerary Practices in the Kamehameha and Kalkaua Dynasties, 18191953

RALPH THOMAS KAM

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2861-5

2017 Ralph Thomas Kam. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: Poola (stevedores) pull the catafalque of King David Kalkaua in 1891 (courtesy Hawaii State Archives)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

In memory of my grandmother

Anna Lau Kam,

whose death first introduced me

to Western funerals,

and to my uncle Ernest Kam,

who maintained the Chinese traditional

bai san observances for his father

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to the staff of the Hawaii State Archives, Archives of the Hawaiian Historical Society, Bishop Museum Archives, Department of Accounting and General Services Land Survey Office, Department of Accounting and General Services Bureau of Conveyances, and Hawaiian Mission Childrens Society Library.

Preface

The deaths of the alii, of high chiefs, in ancient Hawaii had the most profound impact on their subjects. They tattooed the dates or locations of their chiefs deaths on their bodies and named their children for the day of their death or funeral. Despite the importance of the deaths, relatively little is recorded in Western history. This volume seeks to record in a comprehensive manner the obsequies of the Kamehameha and Kalkaua dynasties that drew thousands and tens of thousands of subjects to pay homage to their chiefs. Taken from journals, Hawaiian and English language newspaper articles and broadsides, Death Rites and Hawaiian Royalty chronicles the changing customs surrounding the death of the chiefs following the introduction of Western funerary practices. To a people with one of the most expressive modes of honoring their dead rulers, the Western obsequies provided a new layer of custom to an already complex form. Instead of replacing funerary traditions, the Western style of lying in state, processions, funerals and burials brought a new level of extravagance befitting royalty. The continued complexity of royal obsequies supports the observation by David E. Stannard in the Puritan Way of Death that in traditional societies the individual is of such importance that his or her life is imaginatively extended through prolonged mourning or multiple burial rituals. The obsequies for the rulers of the Kingdom of Hawaii, some revered as gods, exemplify the impact of the royal Hawaiian way of death on the people of Hawaii.

Introduction

Hala i kea la hoi ole mai.

Gone on the road from which there is no returning.

Hawaiian proverb

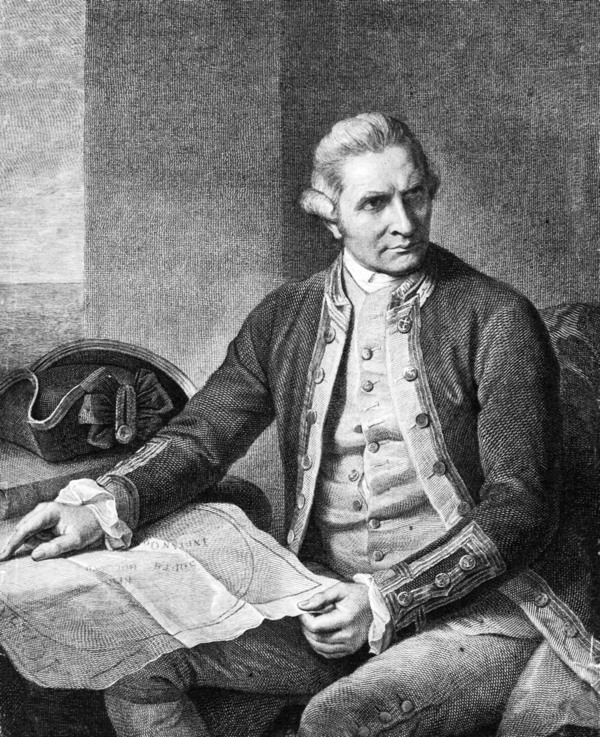

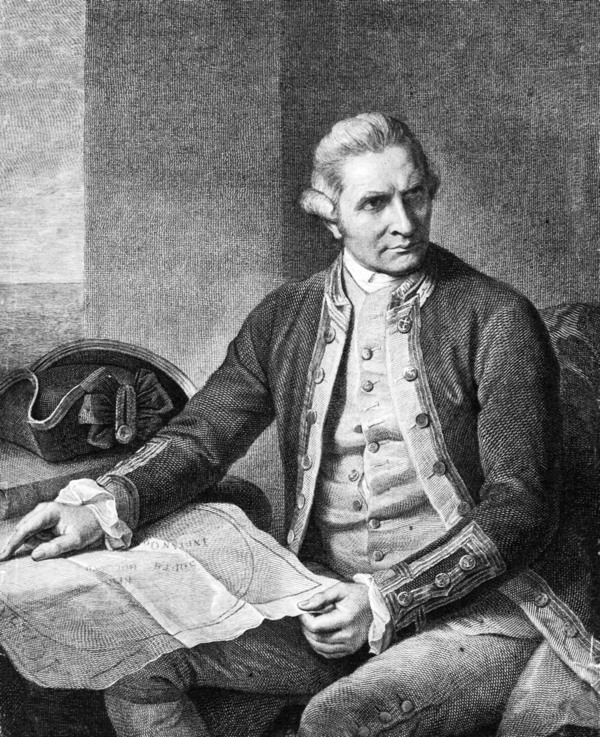

From iwi (bones) hidden at night to mile-long extravagant funeral processions, the practices surrounding the death of royalty in Hawaii took a radical shift after the visit of Captain James Cook initiated permanent contact with the West. But traditional indigenous observances also continued, despite efforts by missionaries to suppress them. The royal Hawaiian way of death formed the contested ground between the traditional activities surrounding the death of a chief and the newly introduced Western practices.

Ironically reports of the treatment of the British explorers corpse and its dissection after his death at Kaawaloa on the island of Hawaii graphically introduced the world to the traditional Hawaiian post-mortem customs. Bishop Museum retains a funerary artifact of the time. Item 1217 is described in a catalog of its holdings as large wooden trough in which the bodies of the alii were dissected. The intestines and flesh were burned or cast into the sea; the bones were carefully cleaned and hidden in some cave. But the post-mortem treatment of Cook would soon be a fleeting custom. The royal Hawaiian way of death went from the secreting of bones to hidden burial caves in the dark of night to the ostentatious displays of funeral parades and burial chapels. As with the rapid adoption of Western ways of war, dress, and architecture, Hawaiian alii, or royalty, also chose to use the royal customs of the West regarding death rituals: lying in state, funerals, processions and burials in conspicuous locations. Despite the adoption of Western practices, some traditions survived through the last royal burial in the twentieth century.

Accounts of the death of Captain James Cook introduced the world to the funerary practices for Hawaiian royalty, practices that would disappear within a couple of decades (courtesy Hawaii State Archives [PP-70-1-039]).

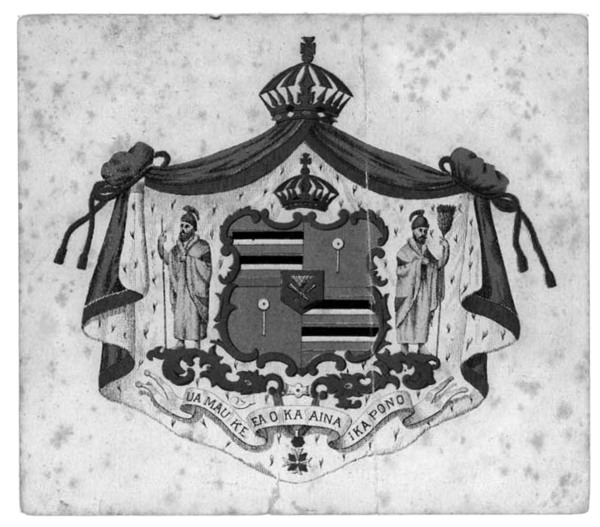

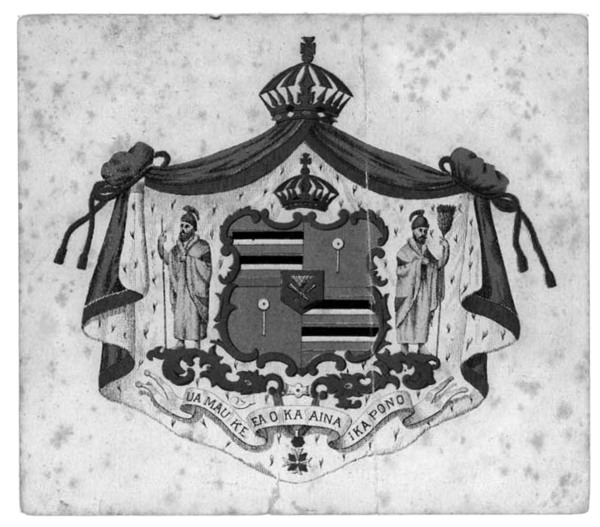

The changes in funerary customs did not take place immediately following contact with the West and establishment of the Kingdom of Hawaii, and at no point did all traditional practices cease. Several deaths of alii took place after contact with Western explorers but before the Western practices took root. Kameeiamoku, grandfather of Kuini Liliha and one of the twin advisors to Kamehameha I who appear on the Hawaiian royal seal, died in Lahaina, Maui, in 1802. Keeaumoku Ppaiahiahi, father of Kaahumanu, the favorite wife of Kamehameha, died in 1804. Namokuelua, the first wife of John Young, Kamehameha the Greats war companion, died the same year, on July 20, 1804. The brother of Kamehameha and grandfather of Queen Emma, Keliimaikai, died in 1809. A year later, in 1810, the other haole or foreign war companion of Kamehameha, Isaac Davis, died. Despite the high rank of the deceased, few accounts record the ceremonies attached to their deaths and burials, though one may assume that traditional practices continued. That certainly was the case in the treatment of the wife of Don Francisco de Paula Marin in 1811, which he described in his journal as threw away the bones of Marins wife. Though Marins term is not accurate, it is the same one used to describe for the burial of Keliimaikai, brother of Kamehameha I.

Kameeiamoku, one of the twin advisors to Kamehameha, appears on the royal seal. He died in Lahaina, Maui, in 1802 (courtesy Hawaii State Archives [PP-17-10-019]).

At least one element of traditional practices from that time has been preserved. A traditional funeral chant, or kanikau, written in 1804 by Kaahumanu for her father survives:

Beloved art thou,

And thou also,

You two chiefs,

The two high chiefs at Pueoula

Kahai, ruler of the island, Kahai the chief,

The sacred, heavenly emanation of Kne.

He is the heavenly thunder that rumbles on,

That rolls away to the presence of Wkea.

It roars in heaven for Kalanihonuakini,

My chiefly father.

Next page