Some signs are almost non-existent: a mere whisper of a trace, the detection of which may well be beyond the scope of this book, but sometimes a sign is very obvious: a tree stump covered in the feathers of a Blue Tit positively shouts Sparrowhawk at the budding nature detective.

Ever since the first human climbed down from the trees, the art of tracking and being tuned in to the world around you has been a matter of life, death, going hungry or eating well.

Long before the advent of the supermarket, being able to find your dinner meant much more than identifying which aisle the frozen pizza could be found in. The original takeaway would run around and hide and do all it could to avoid being consumed, so our ancestors were kept on their toes. They would have had to interpret the signs and subtle clues left by their fellow species in order to avoid starving to death. Following the signs left by your quarry, or indirectly looking for the signs left by other predators which may well have lead to a fresh kill, were paramount to daily survival.

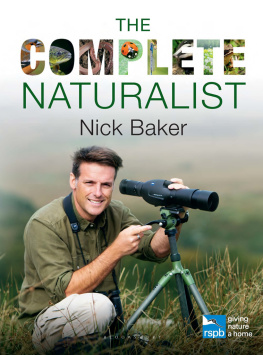

In some ways weve come a long way since then, and you may well argue that, other than for those who still hunt, these skills are redundant, the relics of a past beast. Yet hunting takes many forms: the naturalist armed with a camera may be trying to track down a subject in the quest for a perfect photograph. Using the available evidence can put the photographer in the best place for a shot any fool can look, but only a good tracker looks in the right place. So for us professional (or aspiring) wildlife cameramen, naturalists and ecologists, being able to decipher the multitude of signs all around us is the difference between getting the information, the sighting, the photograph or the film we want and going home unsuccessful.

Trackers funnel

A North American book I found recently describes the process of investigating animal signs and narrowing down the possibilities of which species may have left them as a trackers funnel. Awareness of whereabouts you are in the world and then which particular habitat youre in are essential first stages in making an accurate identification.

Although some animals are generalists and occur virtually everywhere, most have specific habitat requirements. Being aware what these are will help to fine-tune your tracking skills. For example, take the Red Squirrel. You will not find signs of it everywhere, as it mainly exists in the bioregion of Eurasia and in the ecoregion of northern Europe. Its preferred habitat narrows down the sites where youre likely to find it still further it favours coniferous areas of northern forests that are not populated by the ecologically dominant and introduced Grey Squirrel. So unless you are standing under some pine trees in a northern European forest, you are not likely to find the tracks or other signs of this species. Initially, you may need to refer to field guides, but in time a lot of information will become programmed into your head and you will sift through it in seconds.

Part of the process of tracking is getting a sense of what you might expect to find living in any given habitat or bioregion. You wont get Red Squirrels leaving tracks in estuary mud, for example.

Get connected

What made that track? is one of the most natural questions in the world. I believe that an intimate connection with the natural world is whats missing in many of our lives. If we as a species can reconnect on many levels with the world around us and with the latent tracker inside ourselves, then I believe we have a chance, a future as a species. So to take the argument to its ultimate conclusion: although the art of tracking, for most of us, is no longer directly a matter of life and death, the process of connecting with nature is.

How to use this handbook