Chapter One

TRACK IDENTIFICATION

Watching a good tracker at work can be pretty amazing. Making sense of scratches and impressions left in the earth, bent grasses, and shed hairs is a skill few folks in the new millennium ever need to learn. But it wasnt always that way. Tracking and hunting skills were once the equivalent of todays college degree, and they were passed on to every youngster from early childhood. Like tanning hides and making soap, these skills long ago became obsolete in a world increasingly dominated by technology. The finer points of tracking became blurred with time, and myths sprouted up like toadstools on a fallen tree.

There is nothing instinctive about tracking; only intellect and education can enable a tracker to discern that this impression shows the right front and hind hoofprints of a white-tailed buck, impressed during a hard rain two days prior to when this photo was taken.

The first five chapters will help dispel superstition and exaggeration about tracking with solid empirical knowledge. Well learn about the nuts and bolts of locating a species of animal by analyzing its environment, learning its routines by interpreting the sign it leaves, and by tracking it to a feeding, watering, or denning area where it can be observed. Also covered are the tricks and tools most valuable to avoid being detected as you stalk within visual range. Much of the information presented in this section is generic, making it applicable to species not covered specifically in this book, to diverse types of terrain, and even to exotic species on other continents. If you have talent for tracking cougars in Montana, you also possess the basic skills needed to track leopards in Africa.

A warning is in order at this point: Trailing wild animals is a fascinating pastime, but their meandering paths can lead to remote country. Tracking yourself back out is never a good gamble, because snow, rain, and even wind can erase your trail, sometimes in a matter of minutes. Get a quality map compass, a detailed topographic area map, and a solid working knowledge of both before embarking on any tracking exercise. Always carry these items with you in the woods.

Animals carry a magnetic neural compass in their noses, but humans get lost easily without a compass and a map of the area theyre exploring. Carry a GPS if you like, but rely on a virtually infallible compass for navigation.

Reading Tracks

Reading tracks accurately requires a trained eye. Just as a seasoned forester can point out a blue spruce in a forest where most laymen see only trees, an expert tracker can detect and identify tracks invisible to others because he or she knows what to expect. A tracker knows how to recognize and mentally assemble partial impressions into complete tracks, and how to use the arrangement of those imprints to arrive at an accurate explanation of what the animal was doing when it passed through. A veteran tracker knows what species are likely to inhabit an area by the terrain, flora, and fauna that he seeshe doesnt expect to find beavers in a desert or tree squirrels on a prairieand his eyes automatically search for spoor left by animals that have not been seen yet.

This pair of left-side coyote tracks (front on left, hind on right) were made just hours earlier, after dew-moistened sand had dried to a hard crust. Placement indicates an easy lope; hind food shows the animal made a slight turn to the right.

Example: A faint crescent-shaped impression in the ground below tall grasses is read as a whitetails hoofprint. The sharpness of the corners in the print, along with the color, shape, and moisture content of crushed vegetation within it, reveal the age of the track with sometimes surprising accuracy. The depth of the track on one side tells if it is a right- or left-side hoofprint, and maybe even if the deer was pregnant, carrying extra weight.

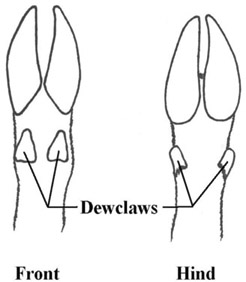

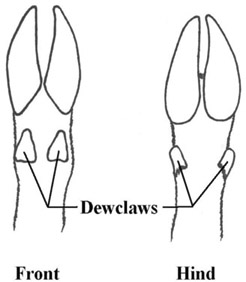

The hooves of a white-tailed deer are typical of ungulates in the order Artiodactyla, being cloven with paired dewclaws that may print on soft soils or snow.

While this book is intended to be carried afield as a reference, there are a number of small pieces of information that every tracker should commit to memory. For example, all cats, from African lions and Bengal tigers to South American jaguars and Canadian lynx, have four toes on each foot. So do canines, but cats have retractable claws that normally do not print, while members of the dog family have fixed claws that register at the front of every track. Bears have five toes with fixed claws on each foot, but their front paws are nearly doglike while the rear paws are shaped much like our own feet. In addition, black bears have short, sharply hooked claws, while a brown bears claws are longer and straighter, designed for digging.

All weasels, including skunks, badgers, and wolverines, have five toes on front and back paws, but the size and other characteristics of their tracks make it possible to identify individual species. Rabbits and hares have four toes on each foot, but their distinctive track patterns are similar only to those of tree squirrel, which have four toes on the front feet and five on the back, and are much smaller.

Another quadrupedal trait is that all species, hoofed or pawed, step down with most body weight on the outside of the soles, which maximizes stance width and stability, and makes the outermost toes largestopposite the bipedal human design in which the big toes are innermost.

Youll still need a reference, however, because for every rule there are exceptions. The common muskrat, for instance, has five toes on each foot, while the closely related round-tailed muskrat has four on the front and five on the rear. The North American gray fox is unique among canids in having semiretractable claws that can be extended to enable it to climb trees. And while most quadrupeds have forefeet that are larger than hind feet because a running gait plants most force against the front paws or hooves, the stealthy bobcat possesses four equal-size feet that give it perfect balance when it freezes midstep while stalking prey.

TRACKS IN MUD

Trackers are seldom fortunate enough to find an obvious trail of perfect, complete prints, but wet sand, clay, or mud along the banks of lakes and streams will nearly always provide a few tracks distinct enough for positive identification, and for even a good plaster cast (explained later). Every animal in an area can be counted on to visit shorelines to drink or feed, or to escape predatorshares freely take to water when pursued because many predators break off pursuit rather than swim after them. Birds, reptiles, and even bats are among regular visitors to watering holes, while some animals, like beavers, muskrats, and nutria, live there full-time. Careful survey of a muddy bank can provide an accurate roster of almost every species within a mile or more, including birds, turtles, frogs, and even the clams that serve as food for numerous carnivores and omnivores.