Publication of this book is made possible in part with the assistance of a Challenge Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, a federal agency that supports research, education, and public programming in the humanities.

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA

http://iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

Orders by e-mail iuporder@indiana.edu

2003 by Daniel B. Reed

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photo copying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Reed, Daniel B. (Daniel Boyce), date

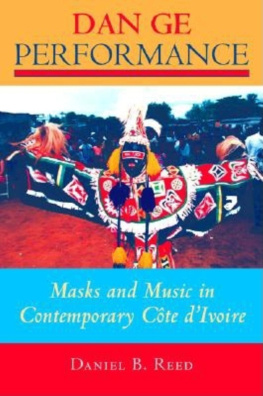

Dan Ge performance : masks and music in contemporary

Cte dIvoire/ Daniel B. Reed.

p. cm.(African expressive cultures)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-253-34270-8 (alk. paper)ISBN 0-253-21612-5

(pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Dan (African people)Rites and ceremonies. 2. Dance

Anthropological aspectsCte dIvoire. 3. Dan (African

people)Music. I. Title. II. Series.

DT545.45.D34 R44 2003

793.3196668dc21

2002154305

1 2 3 4 5 08 07 06 05 04 03

All ethnographic research for this book was conducted prior to 1999, when the first coup in Ivorian history brought to an end the long period during which Cte dIvoire was known as a haven of peace, stability, tolerance, and relative prosperity in the West African region. In September 2002, as this book was in press, another coup attempt was made which quickly descended into a civil war that has divided the country. At the time of this writing, a fragile cease-fire is holding, but the conflict is far from resolved. Worst of all, the ethnic, religious, and regional tensions that are central to this conflict, and which have worsened considerably since the death of Flix Houphet-Boigny in 1993, have in the context of this conflict reached the level of a humanitarian crisis. Muslims and northern immigrants, once drawn to Cte dIvoire because of its economic opportunity and openness to foreigners, are either hiding out in mosques or fleeing the government-held areas of the country following weeks of harassment and violent attacks. Meanwhile, tens of thousands are fleeing the rebel-held north in search of food and shelter. At the time of publication, where this crisis is headed is unknown, but what is clear is that the cosmopolitan Cte dIvoire described in this book is now history, having been replaced by a country torn apart by tensions that for nearly four decades were transcended for the common good.

As a result of this crisis, communication with my consultants has been even more difficult than usual. I have received word from only a few of my consultants and colleagues, via e-mail; at time of press, I do not know how most of the people central to this book are faring in this time of crisis. Thus I begin this book with a declaration of hope not only that my consultants and colleagues all are safe and well but that, somehow, a peaceful solution can be found that will guide the country out of this morass and back to the kind of tolerance and stability that formerly characterized Cte dIvoire.

This book results from the collective efforts of many people to whom I owe gratitude, especially my dear consultants and colleagues in Cte dIvoire. First and foremost I thank my primary consultants Biemi Gba Jacques, Gueu Gbe Gonga Alphonse, Goueu Tia Jean-Claude, Gba Ernest, Gba Gama, Oulai Thodore, Mameri Tia Thomas, and Amso Edomtchi. To these primary consultants and to the many other Ivorians who were so generous with their time, I offer profound thanks, particularly for their permission to use the results of our interactions in publication. I also thank everyone at LInstitut National Superieur des Arts et de lAction Culturelle, especially my mentors and friends Paul Dagri and Adpo Yapo. The staff at Centre Culturel Americain I thank for their support and help. Thanks as well to Biemi Alain for his eleventh-hour e-mail translation assistance. For their friendship and hospitality during stints in Abidjan, I thank the Dagri and Yapo families and fellow Fulbrighters Susanna DeBusk and Melissa Martin. I express deep appreciation to the Biemi family in Bil and the Mameri family in Doul for their generous hospitality during our periodic stays in their compounds. My friends Emmanuel and Nana Fremah Yankey of Yamoussoukro deserve special thanks not only for their hospitality but also for nursing me back to health in 1994. Finally, I thank my first research assistant Tiemoko Guillaume and his family for putting me up, putting up with me, and introducing me to Dan life during the summer of 1994.

I also have many people on the western side of the Atlantic to thank for this books outcome. To many people I owe thanks for their repeated and careful readings of early drafts of this work, for their helpful discussions and debates, and for their inspiration, guidance, and concern. Ruth M. Stone has been a mentor in every sense of the word. She has consistently encouraged and nurtured my work, even and especially when I felt like I was going out on a limb, and for this I thank her profoundly. Thanks to Patrick McNaughton for his inspired view of art and his ever-present sense of humor. Sue Tuohy I thank for reminding me to write from my passion and to stay in touch with why ethnomusicology matters. I thank Roger Janelli for his kind yet critical feedback and John W. Johnson for his enthusiasm and encouragement. Thanks also to Bill Siegmann and an anonymous reader who offered insightful comments that were particularly instrumental in determining the books final form.

Many others have offered ideas, challenges, practical advice, and vital training. I thank Kassim Kon, Emmanuel Yankey, Patrick OMeara, Brian Winchester, Henry Glassie, John McDowell, Dorothy Lee, Beverly Stoeltje, Michael Jackson, Paula Girshick, Lester Monts, and the late Ronald Smith for all they have contributed to my development as a scholar. To Ruth Aten, Camille Rice, Velma Carmichael, Jan Thorns, and Susan Harris I offer sincere thanks for their patience and support. I thank Hande Birkalan and Susan Oehler for spirited conversation and for reading early dissertation chapter drafts. John and Erica Lindamood I thank for their insightful readings of paper drafts and proposals over the years. Thanks to my brother Tim Reed for helping with the challenging Zaouli transcription, and to Alan Burdette at the SAVAIL Lab at I.U. for helping me stretch Finale in order to render this transcription on computer. Rob Grossman, thanks for the fabulous photo. Thanks to my cohorts in Monkey Puzzle Nils Fredland, Nicole Serena Kousaleos, Jerry McIlvain, and Dan Schumacher for keeping me laughing through the many stressful years of research and writing.