DAVID BRODY is associate professor of design studies at Parsons School of Design, the New School.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2016 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2016.

Printed in the United States of America

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-38909-7 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-38912-7 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-38926-4 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226389264.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Brody, David, 1968 author.

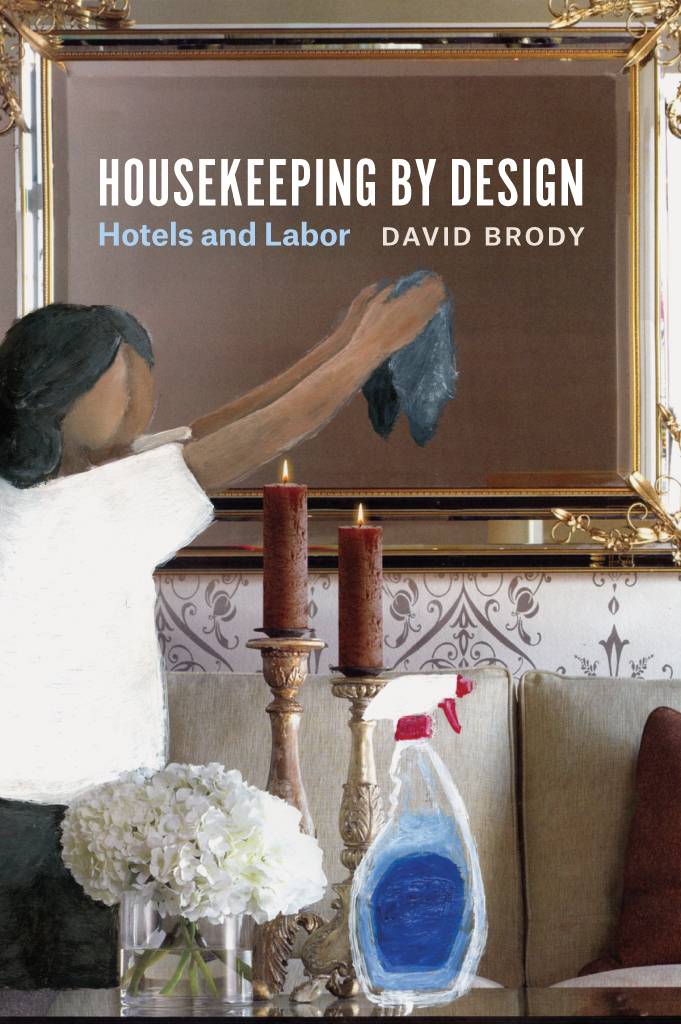

Title: Housekeeping by design : hotels and labor / David Brody.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016007243| ISBN 9780226389097 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226389127 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226389264 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Hotel housekeepingUnited States. | HotelsUnited StatesEmployees. | HotelsUnited StatesDesign and construction. | Sustainable buildingsUnited StatesDesign and construction.

Classification: LCC TX928 .B764 2016 | DDC 647.94068dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016007243

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

It was September 3, 1984. I was sixteen and my brother Jonathan was thirteen. Since the new school year was beginning the next day, my parents decided that we should go out for an end-of-summer celebration. We took two separate cars to Tony Romas, a fairly casual chain restaurant famous for its ribs. The drive from our house in Potomac, Maryland, to Bethesda was uneventful, and I do not really remember the meal, but what I do remember vividly was the drive home with my brother. About five minutes into the twenty-minute trip we left my parents car behind at a traffic light. I sped ahead quickly and continued driving along a series of one- and two-lane roads until I got just outside our tract housing development. Approaching Trotters Trail Road from Bells Mill Road, we noticed a fire truck. This was not a common occurrence in our suburban neighborhood, so Jonathan shouted, Follow it!

I did not have to be encouraged. I sped up and made the left into our neighborhood, following on the tail of the giant red truck. Outside of accelerating, which is never an issue for a sixteen-year-old boy, I did not have to deviate from my planned route. The truck appeared to be going along the same path that I would have taken home. It was after making the left onto Crossing Creek Road, and driving about a hundred feet down that streets steep hill, that I realized something was amiss. The truck decelerated, as it followed the bend in the road to the right and mademuch to my jaw-dropping amazementthe right turn into our cul-de-sac driveway.

In front of our house were two other fire trucks. My parents arrived a few moments later and did exactly what you are not supposed to do in these situations: they ran into the house. The firemen urged us not to follow. My brother and I did not need this encouragement. We sat silently as smoke billowed out of open windows and the roof. I did not see flames, but the dark plumes made it obvious that something had gone wrong. My parents emerged minutes later carrying, of all things, our bar mitzvah photo albums. The fire marshal arrived about thirty minutes later and explained that there was extensive smoke damage throughout the house and that we would not be able to live there for some time. Lightning, we were told, had hit the television antenna (remember, this was 1984) and had traveled down the antenna wire and into the VCR box, triggering an electrical fire. The marshal told us to stay with friends or to get a hotel room.

While the events that followed, including the outrageous attempts at dry cleaning all of the clothes that were in the house and the enormous effort it took to clean the houses ventilation ducts, took a toll on my parents patience and goodwill, it is the hotel story that developed out of this fire that continues to intrigue me. The fire and my three-month hotel stay at the Bethesda Marriott inspired this book.

The Bethesda Marriott is a fairly large hotel located in Bethesda, Maryland, about fifteen minutes outside Washington D.C. The hotel has about four hundred rooms, and while its Brutalist-influenced facade does not foster a bucolic sensibility, the grounds surrounding the parking area are well manicured and verdant. The rooms have always been rather corporate: think staid colonial revival furniture accompanied by banal browns and tans for paint, along with industrial carpeting created to evoke a faux sense of hominess. This is neither a funky boutique hotel nor a luxury property. Most guests stay here because of its convenient location near tourist attractions and corporate parks.

What I remember most about the hotel was the food. The restaurant on the ground floor was American-bistro-meets-suburbia: fantasyland for a teenage boy. Hamburgers, french fries, onion soup, and cheesecake filled the menus pages. Thanks to a generous insurance policy, I had my own room (my brother had decamped down the hall to get away from my parents and me) and loads of unhealthy food during our prolonged stay.

What I remember least about the hotel was housekeeping. Nonetheless, the daily housekeeping at the hotel must have been on my mind. Being at the hotel, with someone there to make my bed and pick up after me, meant that the ritual upkeep of my room at home was no longer paramount. And, like any other teenager, I had things I wanted hidden from view, so I must have been keenly aware of when housekeeping came and what parts of the room they cleaned and which spaces they left alone. However, even though the food is still clear in my mind, the women who came to my room each day to tidy up my messy space, change the sheets, and disinfect the bathroom are barely even a distant memory, obscured by almost thirty years.

As I have discovered while writing this book, the invisible nature of housekeeping at the Bethesda Marriott, and the fact that guests take this labor for granted, is intentional. The hotel industry does everything in its power to make certain that guests do not have to think about the hard work involved in cleaning guest rooms. As each chapter of Housekeeping by Design explores, hotels turn to housekeeping as a way to maintain the guest rooms design integrity, while making certain that guests feel they are staying in a clean and sanitary environment. What is most important about this perception of cleanliness is that the housekeepers complete their job without interfering with the guests stay. Their presenceand perceived lack thereofis critical. People rarely comment on housekeeping after they stay at hotels, unless they experience their room as unkempt. They mention the design of their rooms, talk about the service (usually focusing on things like the front desk), and may describe other amenities at the hotel like restaurants and gym facilities, but housekeeping is an invisible given. It is axiomatic that housekeeping will do its work, but it is even more important that the labor completed by housekeeping gets done without our awareness that any work is actually transpiring.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).