Preface

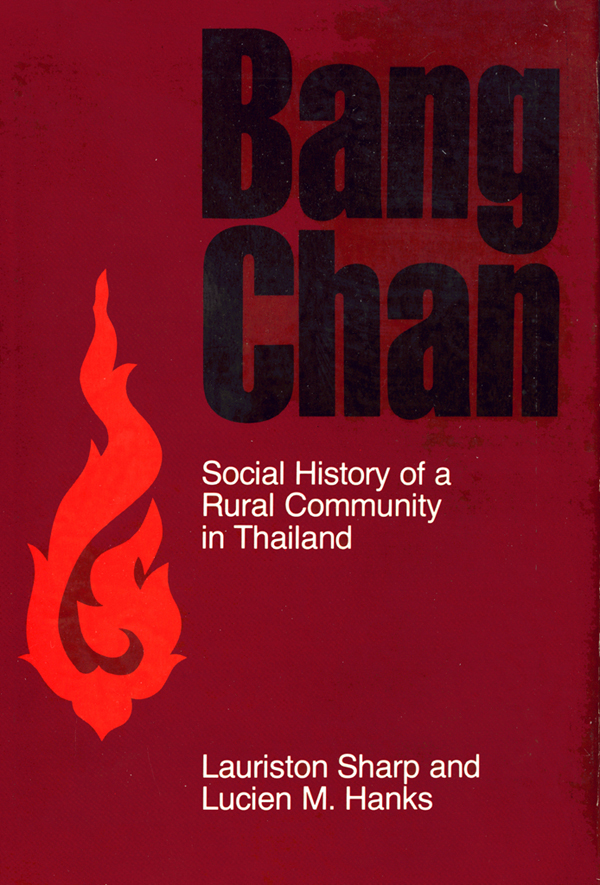

In planning this account of the development of the village of Bang Chan, which had its beginnings over a century ago outside the capital city of Thailand, we sought to provide for the interests of both general readers and specialized scholars. The former, we hope, may move along the mainstream of the story as sampans move along Bang Chan canal during the rainy season, directly and easily. Their passage need not be troubled by the references and footnotes. Wherever possible the technical vocabulary of anthropology has been avoided, although there will be stretches of the journey, as in the section in Chapter 2 headed Economics, the Social Order, and Kinship, in which the channel may seem to be silting up or choked with weeds, as though the dry season had arrived. We believe such muddy sections will prove useful for an attempt to understand the workings of Thai cultural behavior and only hope they will not deter general readers from proceeding on their way.

Other readers may be our colleagues in the study of Thailand and Southeast Asia or in our discipline of anthropology. These students will wish to track down references, question our assertions, and search out evidence for our judgments. We welcome them to the footnotes and the references. Most of the references deal with conventionally published materials, listed in the Bibliography. Exceptions are unpublished field notes cited with initials plus date: HMH 12/20/52. These notes are available in the files of the Cornell University Thailand Project and the Human Relations Area Files in New Haven, Connecticut. Our colleagues and students who have kindly made their field notes available and the initials by which they are identified in the files at Ithaca and New Haven are listed on the following page. (Some of our Thai colleagues have chosen to use idiosyncratic initials rather than the conventional ones.)

| AE | Aram Emarun |

| CIW | Loebongse Sarabhaja |

| HMH | Hazel M. Hauck |

| HPP | Herbert P. Phillips |

| JK | Jadun Kongsa |

| JRH | Jane R. Hanks |

| KJ | Kamol Janlekha |

| KY | Yd Nakorn |

| SM | Singto Metah |

| SS | Saovanee Sudsaneh |

| VIC | Vichitr Saengmani |

| The initials LMH and LS designate the authors. |

For the further aid of diligent colleagues we have scattered transcriptions of the Thai words here and there throughout the text. The transcriptions follow the phonetic system developed by Mary R. Haas and Heng R. Subhanka (1945) with a few changes. We have chosen to neglect tones and the glottal stop. Long vowels will be indicated by a superimposed bar, , . The open o we write au , approximated in the au of English auto and taut. Where some confusion may be possible, as in our transcriptions of certain final consonants or semivowels, the reader may refer to the Glossary, where some of our transcriptions are given in Thai. In general we have not tried to transcribe many proper names, writing Bangkok rather than Bngkaug, Bang Chan rather than Bng Chan, though some readers may be surprised to see Srisuriyawongse transcribed as Srsurijawong. We shall let these eccentric forms stand naturally as they fell from the pen.

When there is no real problem of meaning, we shall also be somewhat relaxed in our translations. We know that a wat is normally a complex of buildings that is both more and less than a temple and perhaps better thought of as a kind of monastery. And its inhabitants may not be priests in some technical senses of the word (most of them are not elders, and there are no sacraments in Ther-avada Buddhism). But temple and priest are commonly used by many English-speaking Thai; through the years, in this as in so many other matters, we have fallen in with common usage, and we continue with it here, hoping that we shall not too greatly discomfort the fastidious.

In this work we have sought to complement or supplement other published studies of Bang Chan or the larger cultural context of Thailand which were carried out by associates during the period of our own work, from 1948 into the 1970s, and which are thus pertinent to an understanding of the village in its areal and temporal setting. So we note among books and monographs dealing directly with Bang Chan the work of Rose K. Goldsen and Max Ralis (1957), Jane R. Hanks (1963), Lucien M. Hanks (1972), Hazel M. Hauck et al. (1956, 1958, 1959), Kamol Janlekha (1957), Herbert P. Phillips (1965), Lauriston Sharp et al. (1953), and Robert B. Textor (1973a, 1973b). A neighboring Siamese village is described by Howard K. Kaufman (1960), and James B. Hendry (1964) makes comparisons with a village in southern Vietnam. Works by our students on the larger Thai scene include studies of other Thai villages by John E. deYoung (1955), Jasper C. Ingersoll (1963), and Konrad Kingshill (1960); of Thai economics by Eliezer B. Ayal (1969) and James C. Ingram (1955, 1971); of government and administration by Charles F. Keyes (1966, 1970), Akin Rabibhadana (1969), and David A. Wilson (1962, 1970); of educational development by David K. Wyatt (1969); and of the Chinese by G. William Skinner (1957). Finally, Frank J. Moore (1974) has provided us with the latest in a series of handbooks concerned with the polity and society of the Thai nation.

A project such as the Bang Chan study resembles a May Day dance. Some erect the pole with its streamers while others tamp down the turf, teach the steps, choose the music, or prepare the May wine, and still others form the audience, encouraging all to do their best. Each is indispensable. So with our sponsors, fellow workers, advisers, students, friends, and informants: every one contributed in some special manner to the achievement of the final result. Though they share no responsibility for the present text, we hope they may gain some satisfaction from having contributed to it.

Our financial sponsors for the work in Bang Chan were the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, the U.S. (Fulbright) Educational Foundation in Thailand, the Social Science Research Council, the American Philosophical Society, and Cornell University. In Thailand we enjoyed the cooperation of the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of the Interior, the Ministry of Public Health, the Ministry of Education, the University of Agricultural Science (Kasetsat), the Siam Society, and, early on, the American Embassy in Bangkok.

Our colleagues in research who constantly enhanced our understanding of details and the context of the Bang Chan scene were Anusith Rajatasilpin, Aram Emarun, Jane R. Hanks, the late Hazel M. Hauck, Jadun Kongsa, Kamol Janlekha, Loebongse Sarabhaja, Herbert P. Phillips, Saovanee Sudsaneh, Singto Metah, Tasanee Hongladaromp, Robert B. Textor, Titaya Suvanajata, Vichitr Saengmani, and Warin Wonghanchao. Among our many friends and advisers we depended particularly on the late Phray Anuman Rajadhon and Siribongse Boon-Long.