j. j. coulton

r. r. r. smith

Oxford Monographs on Classical Archaeology

The series includes self-contained interpretative studies of the art and archaeology of the ancient Mediterranean world. Authoritative volumes cover subjects from the Bronze Age to late antiquity, with concentration on the central periods, areas, and material categories of the classical Greek and Roman world.

other titles in the series include:

Children in the Hellenistic World

Statues and Representation

Olympia Bobou

The Dodecanese and the Eastern Aegean Islands in Late Antiquity, ad 300700

Georgios Deligiannakis

Late Classical and Hellenistic Silver Plate from Macedonia

Eleni Zimi

Greek City Walls of the Archaic Period, 900480 bc

Rune Frederiksen

Komast Dancers in Archaic Greek Art

Tyler Jo Smith

Roman Theatres

An Architectural Study

Frank Sear

Relief Sculpture of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus

Brian Cook

Brickstamps of Constantinople

Volume 1: Text

Volume 2: Illustrations

Jonathan Bardill

The Protogeometric Aegean

The Archaeology of the Late Eleventh and Tenth Centuries bc

Irene S. Lemos

Approaches to the Study of Attic Vases

Beazley and Pottier

Philippe Rouet

Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World

Kenneth D. S. Lapatin

The Late Mannerists in Athenian Vase-Painting

Thomas Mannack

Naukratis

Trade in Archaic Greece

Astrid Mller

Hellenistic Engraved Gems

Dimitris Plantzos

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox 2 6 dp , United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Christian Niederhuber 2022

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2022

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022930108

ISBN 9780192845658

ebook ISBN 9780192660558

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192845658.001.0001

Printed in the UK by Bell & Bain Ltd., Glasgow

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

To my parents and Oliver

Preface

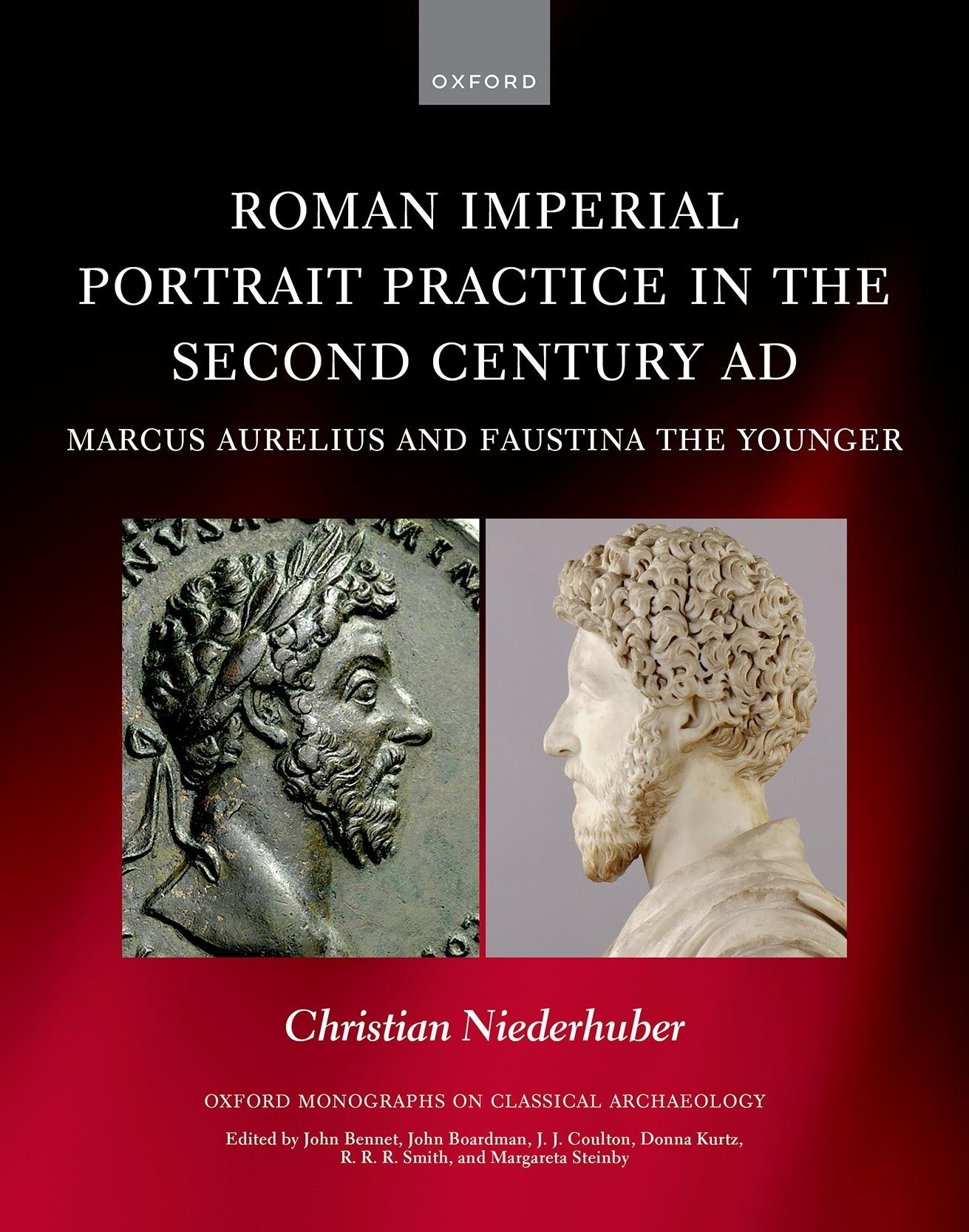

Portraits of Roman emperors and their immediate family members survive in large numbers on coins and in sculpture. They depend on now lost centrally defined models. This book, a revised doctoral thesis submitted to the University of Oxford, examines what these shared models (portrait types) were for and how they were disseminated.

This study could not have been written without the help and support of many friends and colleagues. I would like to thank some of them here: my supervisor Professor R. R. R. Smith for his guidance, help, and support; A. Burnett, V. Heuchert, C. Howgego, and B. Woytek for discussion of the coinage; and Th. Schrder for sparking my interest in Roman portraiture. I would also like to thank the many institutions, museums, and auction houses that gave permission to publish the many images in this book.

Oxford, 2022

Contents

H. Mattingly, Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum IV. Antoninus Pius to Commodus (London, 1940, corr. reprint 1968).

The Treatises of Benvenuto Cellini on Goldsmithing and Sculpture. Translated into English by C. R. Ashbee (London, 1898).

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum.

F. Gnecchi, I medaglioni romani IIII (Milan, 1912).

Inscriptiones Graecae ad res Romanas pertinentes.

Inschriften griechischer Stdte aus Kleinasien.

Inscriptiones Latinae selectae.

Lexicon iconographicum mythologiae classicae.

Roman Provincial Coinage Online

(http://rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk).

Scriptores Historiae Augustae.

Note to reader: please note that the coins and medallions are not illustrated to scale.

It has long been recognized that the portraits of Roman emperors and their immediate family members (imperial portraits) from the age of Augustus to around the middle of the third century ad are not unique representations but in many cases show a remarkable accordance in the rendering of certain iconographic details such as the arrangement of the hair.

To investigate these processes, this study is primarily concerned with the appearance and details of the imperial portrait heads with their replicated individualized portrait identity (and posture)frequently the only part of the portraits surviving. The term portrait is, accordingly, used in a very narrow sense. One must be aware, however, that in sculpture the head was never a self-sufficient monument on its own in ancient times. It was always combined with a statue or bust supportthe primary forms of display of the imperial family around the empireas a vital part of the message the portraits were intended to convey in their local context. Furthermore, the statues were set on an inscribed base, as an integral element of the monument. The favoured costume choices for emperors portraits in the second century were cuirassed, standing for the military imperator, andmuch less commonnaked with weapons (heroic costume). The toga costume was still sometimes used, but in contrast to the first century ad it was rarely employed in the period discussed here. The empress, in comparison, was represented draped with tunic and mantle. All of these choices were not restricted to imperial portraits but also used for private portraiture.

The archaeological and textual evidence suggests that the production of imperial portraits reached its height in the second century ad and it is absolutely clear that the surviving portraits are only a fraction of what once must have existed. On the scale of this approbationin the following referred to in its entirety as constituting an honorific systemwe are informed by one of the very few contemporary literary sources on imperial portrait practices in this period, a famous letter from Cornelius Fronto to his pupil Marcus Aurelius (