Metanoia

Also Available From Bloomsbury

Present Tense, Armen Avanessian and Anke Hennig

Genealogies of Speculation, edited by Armen Avanessian and Suhail Malik

Speculative Realism, Peter Gratton

The New Phenomenology, J. Aaron Simmons

Philosophical Chemistry, Manuel DeLanda

Philosophy and Simulation, Manuel DeLanda

Introduction to New Realism, Maurizio Ferraris

After Finitude, Quentin Meillassoux

Contents

Illustrations

Semiotic triangle by Andreas Tpfer

Semiotic triangle by Andreas Tpfer

Semiotic triangle by Andreas Tpfer

Semiotic triangle by Andreas Tpfer

Ecos Subterfuge

Rosa x Centifolia purpurea

Maheka La Belle Sultane

Rosa Indica dichotoma. Le Bengale animating

Rosa Indica Caryophyllea. Le Bengale Oeillet

Slaters Crimson China

Abduction in perception

Terrence Deacons Semiotics of the Brain

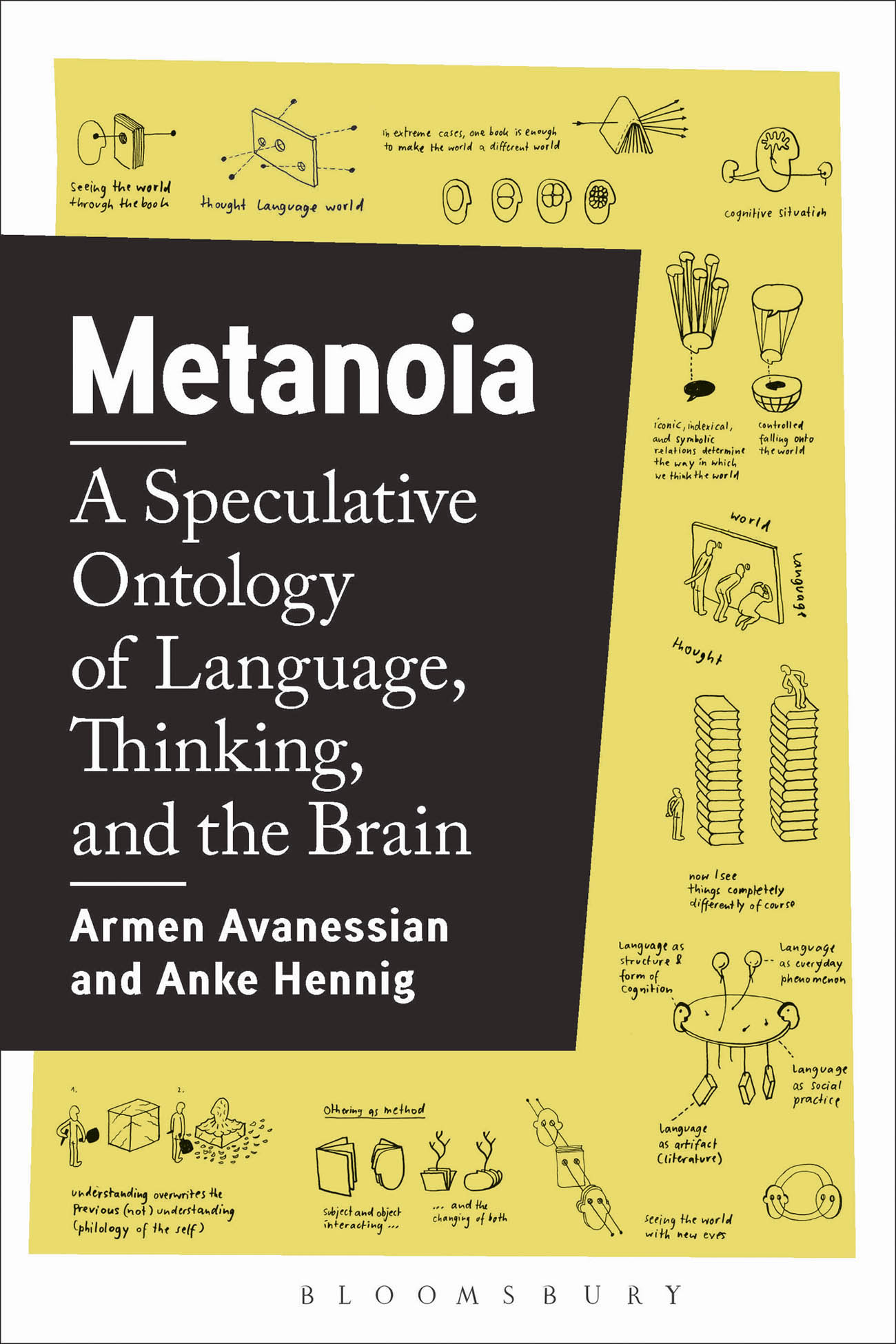

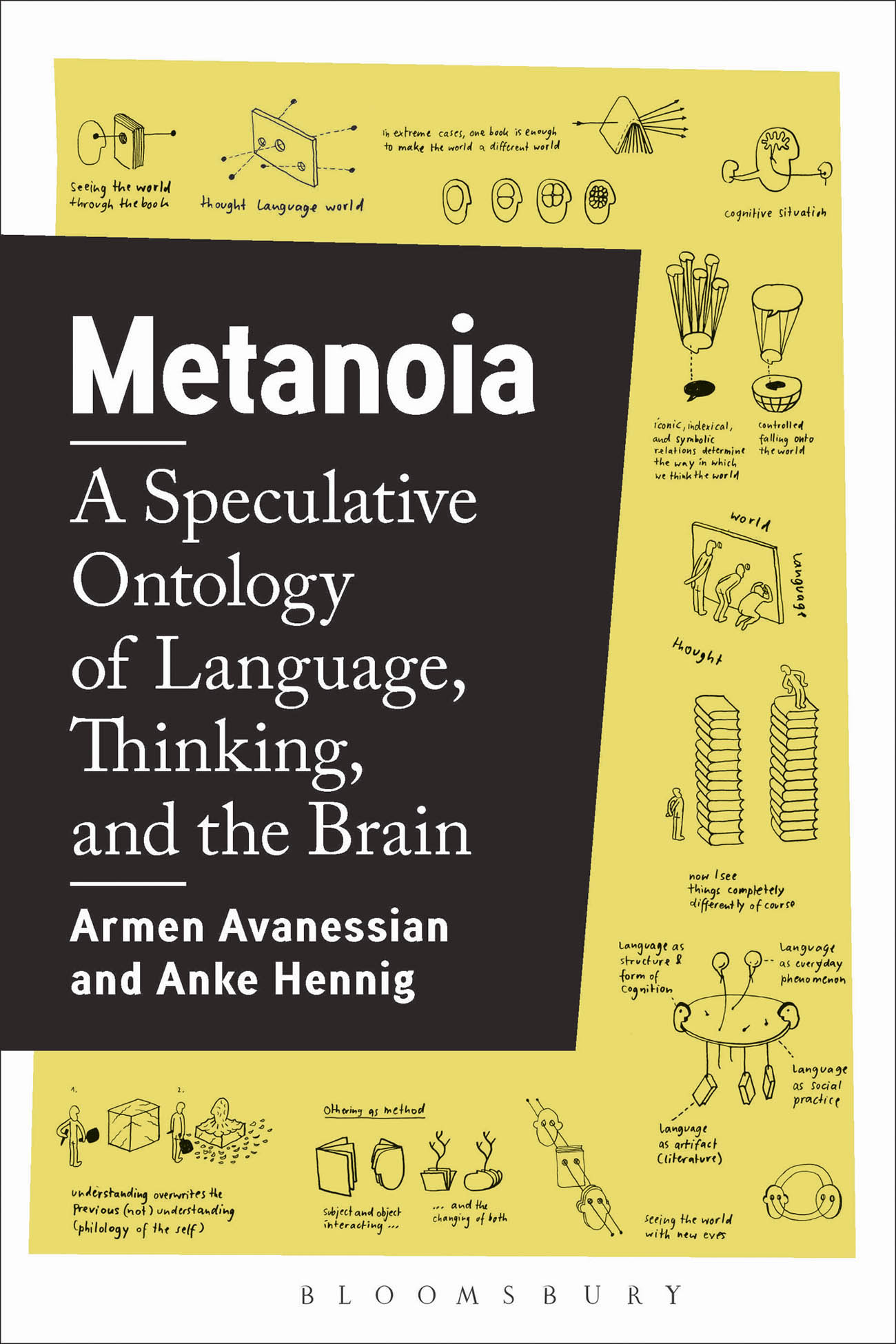

All chapter opening images are from Armen Avanessian, Andreas Tpfer, Speculative Drawing, Berlin: Sternberg Press 2014.

The book before the reader brilliantly deals with the theme of metanoia. Drawn primarily from religious language in the Christian tradition, metanoia is often mistranslated as repentance. More properly the term should be translated as conversion. Metanoia refers to a fundamental transformation of ones self, nature, thought, and world. However, it would be a mistake to conclude that the origin of this word indicates that this book is a work of theology. In the concept of metanoia Avanessian and Hennig discern a phenomenon that is far more pervasive than the religious register and its conversions, but that lies at the core of thought and language. There is a power of language, thought, and speech to transform both the subject and the world. How is it, Avanessian and Hennig wonder, that a book, a poem, a conversation, or a thinking can fundamentally transform both the subject and the world? We enter that book, poem, conversation, or trajectory of thought at one end and when we come out the other everything is completely different. Indeed, in such experiences we can scarcely remember who we were and what the world looked like before. So thorough is the transformation that it even transforms our retroactive selves and worlds. We see the past differently than we did before. This is metanoia. In a thinking that traverses speculative realism, new materialism, neurology, structural linguistics, and Peircian semiotics, Avanessian and Hennig seek to determine just how something like metanoia is possible. I will leave the book to the reader for the details of this account, instead using the space of this foreword to discuss both how we might think about the phenomenon of metanoia and some of the implications of the concept.

In what follows I will use language and games as a launching point for discussing philosophy. In linguistic circles it is a commonplace to compare language to a game. Take a board game. A board game has the board upon which it is played, the pieces with which the game is played, and the rules of the game by which moves can be made. Simplifying matters dramatically, the pieces of the game in language would be phonemes, while the rules of the game would be the syntax by which those elements are composed into larger units such as semes, sentences, paragraphs and so on. These would roughly be the paradigmatic and syntagmatic dimensions of language respectively. Competence here would consist in knowing how to make moves in this game; which is to say, knowing how to form sentences or engage in speech-acts.

We can think of philosophies as similar to games and languages in this respect. There is a Plato game, a Lucretius game, a Descartes game, a Hegel game, a Deleuze game, a Heidegger and Badiou game, and so on. Each one of these philosophies has its own phonemes or pieces that inhabit the game and each has rules for making moves in that game. One shows competence in any one of these games not when they can cite the intricacies of these philosophies chapter and verse, but rather when they can make a new move within those games according to the rules governing the game. Compare the Plato game and the Epicurean game, for example. Suppose we were to ask whether or not it is ethical to do the drug MDMA or ecstasy? Now clearly we will not find an answer to this question in the writings of either Plato or Epicurus (or Lucretius) because the drug did not yet exist and therefore could not become a topic of ethical reflection. It is likely that both Plato and Epicurus would be opposed to MDMA, but for entirely different reasons. The goal of Platos philosophy is the purification of the soul so that it will separate from the body at death and go on to the world of the forms. We achieve this goal by living a life of intellect and by turning away from the body and the five senses. If Plato would be against MDMA, it would be for the same reasons that he rejects certain musical instruments, forms of art, and poetic meters in The Republic: they draw out the passions of the body, clouding the power of the intellect, just as the drum is among the anti-Platonic instruments par excellence because it evokes sensuous affects that lead our body to move involuntarily, emphasizing the body and its passions over the intellect. One need only think of the famous dance scene in The Matrix Reloaded to discern the power of the drum and bass.

Like Plato, Epicurus would probably be against the use of MDMA, but for entirely different reasons. In Epicurus the goal of the game is to live the most pleasurable life possible (because pleasure is the moral good) and to minimize anxiety as much as we can. However, while Epicurus treats the pleasurable as the moral good and the painful as the moral wrong, he nonetheless argues that we should avoid forms of pleasure that are either too much trouble to find or that cause pain as a consequence. For Epicurus, the question would then be whether MDMA is too much trouble to get or causes pain (psychological or physical) as a consequence or whether it increases anxiety. It is likely that he would see it as being a negative impact on all these fronts and would thus argue that the prudent person should reject it.

All of this seems remote from issues of metanoia; however, a few things are of interest here. First, we can talk of a philosophy as an alethetics. For Heidegger, truth as aletheia is not a correspondence between a proposition or statement and the independent reality that it depicts, but is rather a revealing or disclosure. Where the correspondence theory of truth holds that truth is a relationship between a proposition and a thing or state-of-affairs such as the claim that the statement that a hammer is a tool for pounding nails if there exists a tool that is for pounding nails, truth as aletheia holds that this assemblage presents or discloses itself as something for the sake of this task; it gives itself in this way prior to any claim we might make about it. The hammer is given differently for, say, the physicist who might encounter it in terms of chemical and atomic composition, mass, position in space, velocity, etc. These are different forms of disclosure. As Avanessian and Hennig repeatedly remind us, disclosure is a dual relation between a subject or self and a world. The self of the physicist and the self of the handyman are different selves, but there are also different

Next page