2022 City University of Hong Kong

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, Internet, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the City University of Hong Kong Press.

The moral right of Nigel Collett to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Division IV, Section 90 of Cap. 528 Copyright Ordinance.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyrighted material. The author and publisher apologise for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

ISBN: 978-962-937-590-4

Published by

City University of Hong Kong Press

Tat Chee Avenue

Kowloon, Hong Kong

Website: www.cityu.edu.hk/upress

E-mail:

Printed in Hong Kong

To Martin Sheppard, who inspired me to write this story

They go forth [] with well-developed bodies, fairly developed minds, and undeveloped hearts. And it is this undeveloped heart that is largely responsible for the difficulties of Englishmen abroad. An undeveloped heart not a cold one.

E.M. Forster, Abinger Harvest

(London: Edward Arnold, 1946), p. 5.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

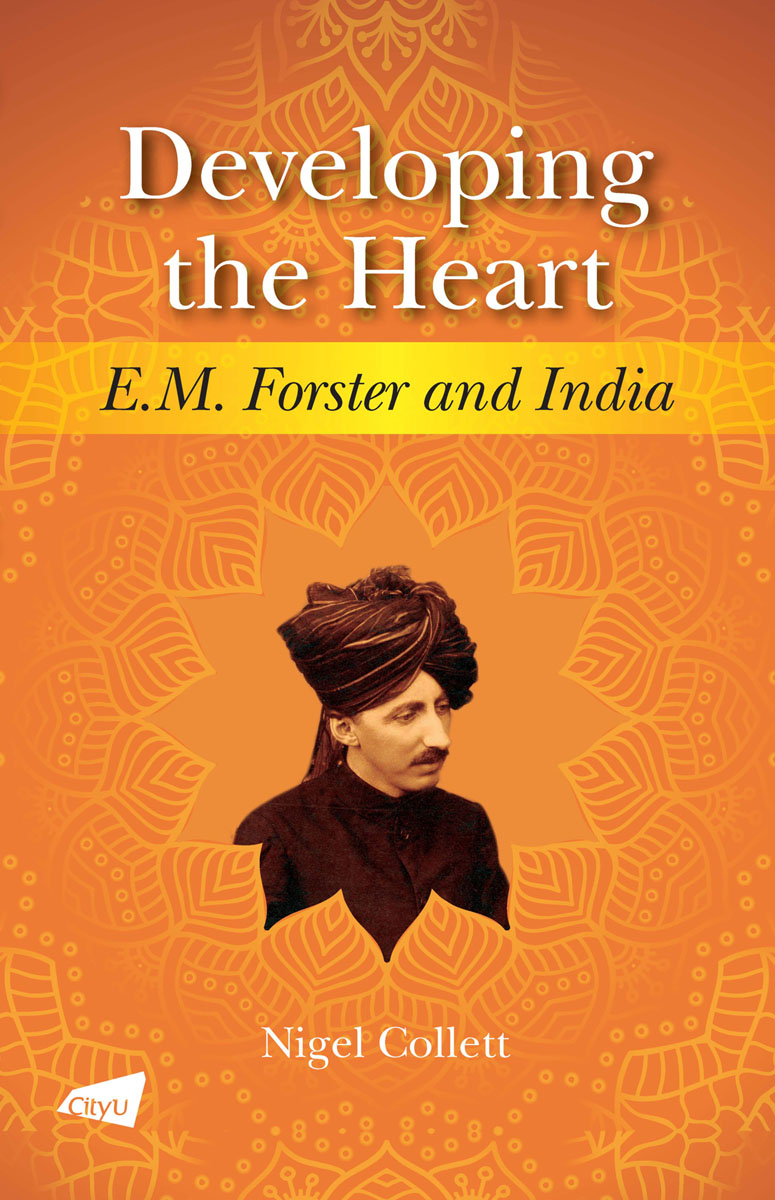

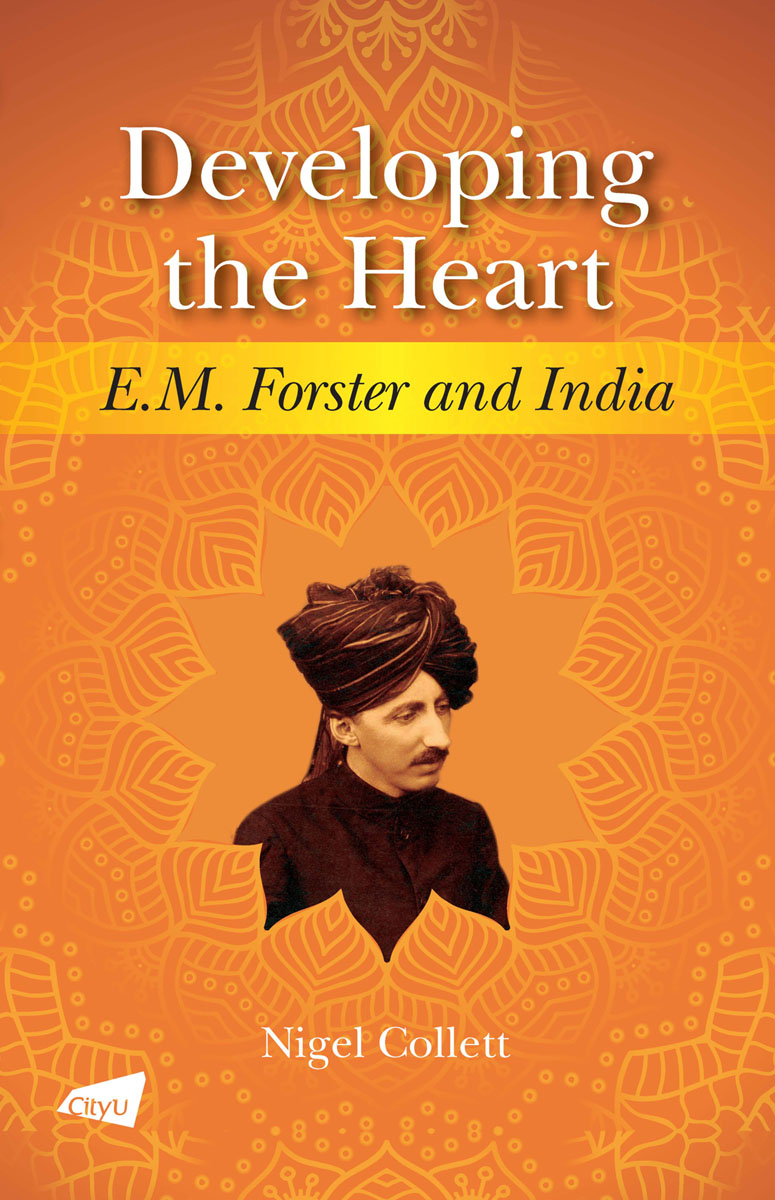

Although Edward Morgan Forster lived to the age of ninety-one, he had within the first half of his life both established and abandoned a position as one of the great novelists of the English language. After A Passage to India was published in 1924, he wrote no more novels. Yet, the reviews, articles, broadcasts, and short stories that he continued to publish until the 1960s are proof that this was not because his muse deserted him. Instead, it is clear that something prevented Forster from writing another novel, and, at least since the publication of P.N. Furbanks official biography of the writer in 1977, it has been generally accepted that this was because he could no longer reconcile writing stories about heterosexual characters with his own homosexual orientation. It is also now generally accepted that Forsters sexual awakening came about due to the love, sex, and friendship that he found in Indians and their country. It is Forsters Indian relationships that are the subject of this book.

India fulfilled Forster and gained him a maturity he had not hitherto found in England. In 1906, when India brought to England (and then to Forster) the young Syed Ross Masood, Forster had his first real experience of falling in love. Masood was the first man to whom he ever declared himself, and when Masood went home to India, Forster followed him there in 1912. It was in India, at the age of thirty-three, that Forster came face to face with the realities of sex. The libido then awakened in him, until then almost dormant, could never subsequently be put to rest. Later, during his second visit to India in 1922, he experienced what was probably the only promiscuous, gratuitous sex of his life. What Forster found in India drove him to seek explanations for, and solutions to, what he saw as the problem of his homosexuality.

Through love and sex, as is often the case for homosexual men, Forster also found friendship. By the time he reached India, he already held strong views about the value of friendship, but these were expanded and moulded by what he came to see as the Indian way of friendship, as well as by the relationships he formed with a very large number of Indian men. Forsters Indian friendships gave flesh to his liberal beliefs and informed his view that loyalty to a friend transcended any loyalty to crown, state, or nation. The Indian friends he made were transgressive in all ways: they were, at least until 1947, when independence levelled the field, subjects of the Empire, the ruling class of which Forster was a member; they were of races and colours discriminated against and despised by many of his countrymen; and they were of faiths, Islam and Hinduism, considered barbarous by his Christian co-religionists. His Indian friends were his beliefs made concrete, and they were vastly important to him.

Forster revealed just how much importance he placed in friendship in his essay What I Believe, penned in 1939 in the darkening days of war. He wrote: Where do I start? With personal relationships. Here is something comparatively solid in a world full of violence and cruelty. He went on, famously:

One must be fond of people and trust them if one is not to make a mess of life [] I hate the idea of causes, and if I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country [] Love and loyalty to an individual can run counter to the claims of the State. When they do down with the State, say I.

It would be false to claim that it was only India that had given him this belief, for it was a view of the world that he had imbibed initially during his time at Kings College, Cambridge. In 1924, he wrote to his friend Malcolm Darling to express this: Kings stands for personal relationships, and these still seem to me to be the most real things on the surface of the earth. It would not be false to claim, however, that it was India that opened his heart to friendships with men of all races, classes, and religions. India drew him into ever-widening circles and enveloped him in a warmth of friendship that he did not find easily at home.

The East, Forster came to see, had a different approach to friendship. Indians in particular, he thought, held it in greater regard than did Englishmen. He put it this way in 1921 in his article, Salute to the Orient!: So if we say of the Oriental, firstly that personal relationship is most important to him, secondly, that it has no transcendental sanction, we shall come near to a generalization as is safe.Forster made in India remained close to his heart, and he did not cease to make friends with Indians until his very last years.

Love for Indians brought Forster a deep love of their culture and country. In this, he was again transgressing, not perhaps as much as in his sexual affairs or in his social contacts, but more publicly, for he made no bones about his appreciation of Indian culture. His contemporaries disagreed. Most Englishmen were largely ignorant of anything Indian and regarded the little they knew as indecent or barbaric. Forster developed a deep understanding of Indian art, sculpture, and architecture, and wrote and broadcast about them for much of his life.

Love, sex, friendship, and affection for the country that had made them all possible, form the substance of his last novel, A Passage to India. This was, for its time, and like his Indian relationships, a novel of transgression. Under the guise of an analysis of the failings of the British Raj and of a young womans search for self-awareness, the novel is, at least in part, the story of a love affair between two men, an Indian and an Englishman. In that sense, it is the story of Forsters own predicament.

The accounts that we have of Forsters life begin in 1977 with P.N. Furbanks magisterial official biography, E.M Forster: A Life. These biographies are unlikely to be superseded in giving a full account of his life. Yet, whilst the story of Forsters love affair with India has been recounted before in outline, particularly in respect of his unrequited love for Syed Ross Masood and his first two sojourns in the sub-continent, the full details of how India affected his life and became fast woven into its texture have not yet been revealed. This book sets out to do this.

Next page