Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Parallax Press

2236B Sixth Street

Berkeley, CA 94707

parallax.org

Parallax Press is the publishing division of

Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism, Inc.

2021 by Renda Dionne Madrigal

All rights reserved

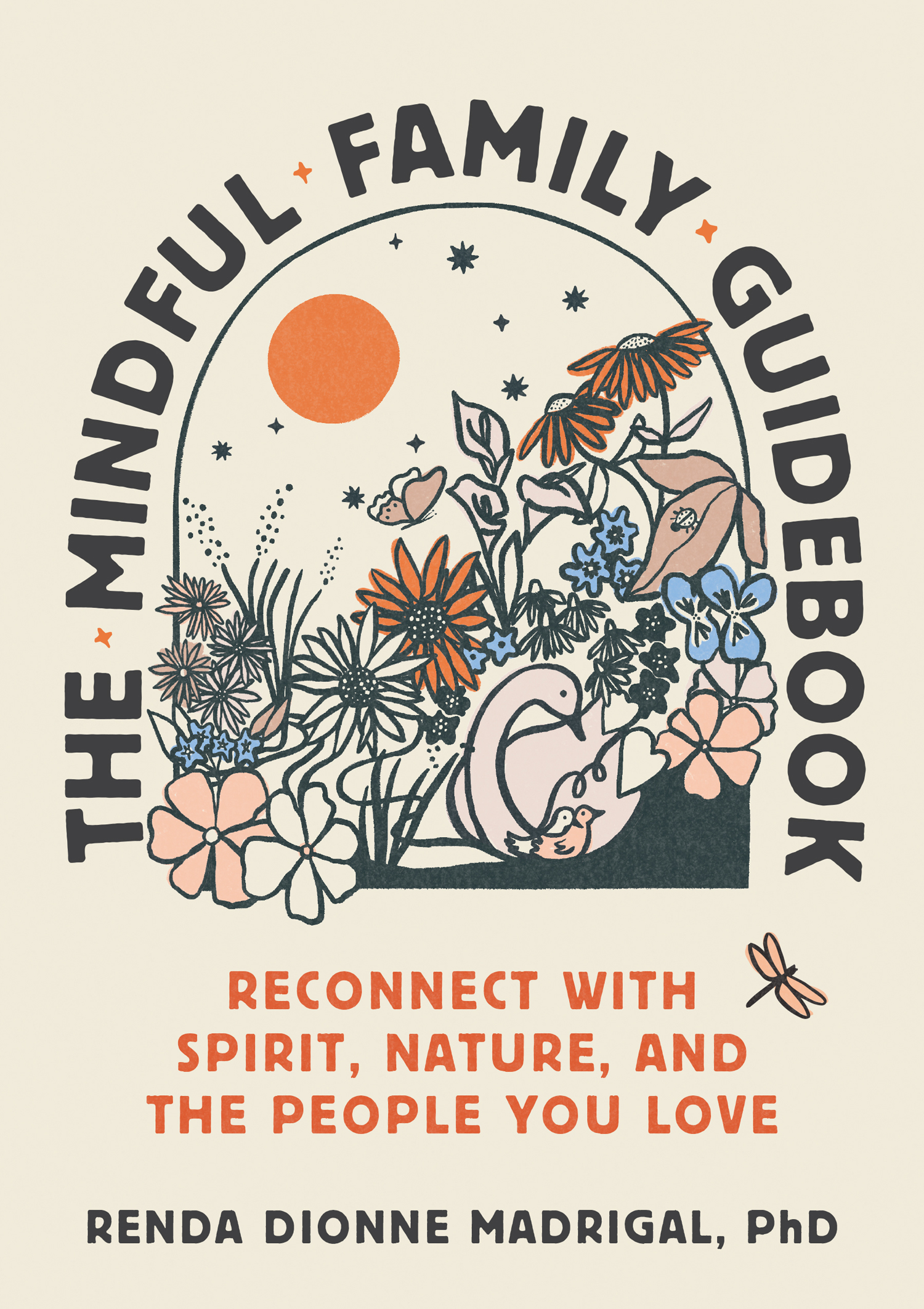

Cover art by Amelia Heron

Cover design by Debbie Berne

Author photograph by Lori Brystan

Ebook design adapted from print design by Debbie Berne

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Madrigal, Renda Dionne, author.

Title: The mindful family guidebook : reconnect with spirit, nature, and the people you love / Renda Dionne Madrigal.

Description: Berkeley, California : Parallax Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021004830 (print) | LCCN 2021004831 (ebook) | ISBN 9781946764782 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9781946764799 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: FamiliesPsychological aspects. | Mindfulness (Psychology) | Manners and customsPsychological aspects.

Classification: LCC HQ519 .M33 2021 (print) | LCC HQ519 (ebook) | DDC 306.85dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021004830

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021004831

Ebook ISBN9781946764799

a_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

For Luke, who made everything possible

And the girls, Isabella and Sophia, my purpose

And my mom and dad, who believed

And, of course, the ancestors

CONTENTS

PREFACE

BEGINNINGS: INITIATION

Once you make a decision, the universe conspires to make it happen.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

So here you areyou picked up the book. Something, an instinct perhaps, led you here. Where will this journey lead? Well, that really depends on you. Lets start with a proper greeting. In a proper welcoming we would be face to face, but since this is a book, Ill have to welcome you with words that are carried on the wind, blown into the pages of what was a tree or into some mysterious electronic font. Welcome to the journeyyour journey.

I have a confession to make. I want to direct your awareness to a more instinctual, ancient orientation. One that has deep roots to sustain not only your family, but all of humanity. A long time ago, what we now call mindfulness was practiced by people all over the world. It is an ancient way of being aware and present to life as it is. In one of the oldest translations of Buddhist texts, the Sanskrit word smrti or mindfulness means to remember; the teachings of the Buddha and his students codified methods of practicing mindfulness that are still followed today. In many ways, this book is about remembering things that have sustained our ancestors and our entire human family for most of the time that we have existed on the planet. Things that we have mostly forgotten in the industrial and technological ages of the last two centuries. Things that matter for our health and happiness as well as for our planet.

This book draws on the knowledge of my heritage, my family, and the teachings Ive received, and, in my turn, given to others. I am a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, the wife of a Cahuilla traditions keeper, and a mother of two girls. I am also a certified mindfulness facilitator and a mentor with the Mindfulness Awareness Research Center (MARC) Teacher Training Program at the University of California, Los Angeles. In my day job, I serve my community as a clinical psychologist.

I started learning about mindfulness in the 1990s when I was in my twenties and in graduate school. A sage therapist told me that if I wanted to ease my own suffering, I should attend a meditation retreat by Vietnamese Zen Buddhist master Thich Nhat Hanh, who was visiting the campus of the University of California, Santa Barbara. I had never heard of him, nor had I attended a retreat before, but I wanted to learn and was willing to try. I was deeply impressed by the wisdom of this humble monk and the gentle happiness of the people around him. This first encounter with mindfulness would lead me to explore the practices in this Buddhist tradition, which gave me a sense of calm joy.

Jumping forward to 2011, I had lost touch with my mindfulness practice, and I was disillusioned with what was happening in my life and in the world. It started with my work life, which had come to feel like a series of stressors and was no longer fulfilling. Then my husband had a heart attack and underwent open-heart surgery. Our finances were drying up and our future looked gloomy and insecure. I didnt know how we would pay our bills. I was overcome with anxiety and dread, and worried that I couldnt be a good mother for my children and that my family would completely unravel. I sank into a deep depression, and somewhere in the midst of this period, a voice came through to wake me up.

I was in my living room. My husband had left the television on to his favorite show at the timeBook TV. Pulitzer Prizewinning journalist Chris Hedges was talking about the percentage of the world population living on less than two dollars a day.

I noticed two things. One: There was a tenderness I felt in my chest when I paid attention with an open heart. It made my own struggles more bearable, not because my suffering was less than theirs, but because I understood the interconnected nature of our suffering; I could be them, and they could be me, but for our circumstances. I could see the causes of our suffering more clearly. The second thing I noticed as was that I was becoming angrier at society as I continued to bear witness to the atrocities going on in the world. Of course, I had heard statements like this about poverty before, but until that day I had never been emotionally impacted. I really heard the words, understood the suffering that lay behind them.

As an American Indian, its easy to be angry when you know your own history. When you understand that over 90 percent of the Indigenous population on this continent died as a result of European colonization; that the people remaining are suffering horrible health outcomes, and that Indigenous communities all over the world live with similar conditions, it is only natural to feel rage and despair.

In my life and practice, I started to see the impact of colonization on people all around me. This clarity both enraged and empowered me. I became worried that my heart would harden and turn black, and about the effect of this negativity on my marriage and my daughters. I couldnt ignore it anymore, but I didnt want to be filled with hate. How could I look at the negativity that exists in the world and not become engulfed in it too? My instincts were telling me that to deal with what was happening in my own life and in the world, I would need to immerse myself in mindfulness practice, and somehow, bring it to my family. Thats when I started wondering how Thich Nhat Hanh was doing.

I knew he lived in France, that he was getting older, and I wondered how much longer he would be actively teaching in the world. I Googled him, and was astonished to learn how accessible mindfulness had become in the United States. When I say accessible, I mean that in the nineties no one was talking about mindfulness for the most part, but in 2011 it was popping up in prestigious Western institutions like the University of California, Stanford, and Oxford University in England. I signed up for a yearlong mindfulness facilitation program at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), then mindfulness programs for teaching families and young people. I set an intention to incorporate mindfulness teaching into everything I did. Year after year, I led groups on Mindfulness for Indigenous Decolonization, a supplement for substance abuse and domestic violence treatment, Mindful Parenting, Mindful Families, Mindful Storytelling, Mindfulness for Social Workers and started a centerMindful Practice Incorporated. But, most importantly, I started and maintained a personal practice of mindfulness on a daily basis.