Table of Contents

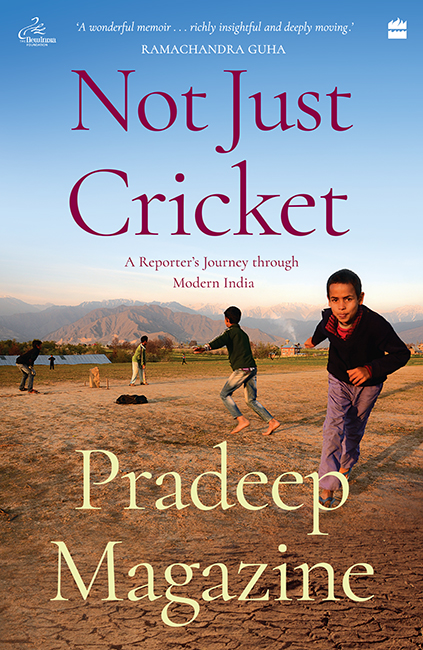

The New India Foundation, based in Bengaluru, uniquely matches public-spirited philanthropy with ground-breaking and relevant scholarship. In the seven-and-a-half decades since Independence, there has been a large body of work produced by Indian historians and social scientists. Taken singly, many of these studies are very impressive; viewed cumulatively, they add up to much less than what one might expect. The chief reason for this is the determining influence on the scholarly practice of one single date: 15th August 1947.

Given Indias size, its importance, and its interest, and given that this is our country, the lack of good research on its modern history is unfortunate. It is this lack that the New India Foundation seeks to address, by sponsoring high-quality original scholarship on different aspects of independent India. Its activities include the granting of NIF Fellowships for highly researched original work, Translation Fellowships for bringing historical Indian language works to English, the publication of books on the history and culture of independent India, organizing the Girish Karnad Memorial Lecture, and the Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay Book Prize.

To my mother, Raj Dulari, who gave me my first lessons in loving-kindness, and father, Kishen Lal, who taught me the value of inclusiveness.

Contents

The house in Karan Nagar had crumbled from neglect, having been uninhabited for nearly two decades. The roof of the three-storey building had caved in at many places and the stairs inside were on the verge of collapse. I still attempted to climb to the small room on the third floor where I had spent most of my early childhood. The armed policeman escorting me was too scared to follow me up those stairs. For him, the climb was not worth risking his life.

For me, the place held multiple layers of tangible and intangible memories as it was there, around fifty years ago, that I had been haunted by imaginary ghosts while preparing to sleep, waiting for the reassuring presence of my mother, who would be busy in the kitchen on the ground floor till late in the night.

Only two of my cousins were still living in Srinagar in 1990 when violent militancy swept through Kashmir. They had to abandon the house. People were protesting in the streets of Srinagar and violence and killing became widespread in the region. Anyone suspected to be an Indian agent was on the hit list of the militants. While those from the majority Muslim community were also being killed, Hindus in particular feared for their lives. Slogans laced with Islamic sentiments in support of freeing Kashmir from India were getting louder by the day. Most Pandit families had begun migrating to Jammu and beyond in the stealth of the night, hoping that normalcy would soon be restored and they could return to their homes.

My parents had migrated from Srinagar in far more peaceful and harmonious conditions in 1964, when my father, a customs official, was transferred to a small township in Haryana (then still Punjab). I visited my grandparents in Srinagar once a year, reviving ties with my relatives and basking in the nostalgia of a childhood that was fast becoming a speck in my memory. By the late eighties, our visits to Srinagar became more infrequent as most of my relatives left their hometown due to a lack of jobs in the Valley. They sought greener pastures in cities far away that may have been formidable and alien but offered economic security and a bright future for them and their children.

My profession as a cricket writer and journalist offered me many opportunities to revive my ties with my lost roots. Working for the Hindustan Times from 2001, I would look for any excuse to do a story in the Valley and let the pangs of the past course through my veins, causing me immense anguish and simultaneously great joy. Migration, city life and job compulsions can make one insensitive and robotic but a whiff of the past lived in innocence and even ignorance of harsh realities makes one human again.

Be it the story of Parvez Rasool, the first Kashmiri Muslim cricketer selected to play for India in 2013, or the separatist politician Sajjad Lones pathbreaking decision to fight the 2009 Lok Sabha elections, I would visit the Valley to gather material on them. These stories held a touch of poignancy tinged with irony for readers, as a Kashmiri Pandit in exile was writing about prominent Muslim figures of the Valley without rancour and even celebrating their successes.

It was on one such sojourn in 2006 that I forced my way into the Karan Nagar locality. The area where we lived was like a ghost town, dotted with rows of dilapidated, empty houses, ravaged by time and utter neglect. For me, it was like visiting a tomb, trying to connect with a past buried in the ruins of those houses, yet alive in my memory.

I had to literally force my way in, as the stretch where the Pandits used to live was, and still is, occupied by the security forces. The Rashtriya Rifles and other units had made the area their headquarters. Permission from them was necessary to make a visit, which I was denied initially. However, when I threatened the officer that I would write about this treatment in the papers, he relented.

On the main road, just before the turn towards the lane leading to our house, I saw the goor (milkman) sitting in his shop. I immediately recognized the old man as the one who would deliver milk to our home every morning. I became emotional and told him who I was. I dont know whether he could really remember me as the child with whom he had once enjoyed playful exchanges. But when he said, Why did you do this to us?, pointing towards the barbed wires and the armed security men, I was left unnerved.

My wife, Mukta, and daughter, Aakshi, were with me. Seeing the red bindi on my wifes forehead, the security men realized we were Hindus. One of them asked me with hissing venom, Why are you talking to these bhan...choo I could not agree with his language and did not share his sentiment, but I did understand where his anger came from. Being in an alien land where the majority consider you an occupying enemy force that kills before it talks must take its toll on ones psyche. I would witness a similar outpouring of rancour from a young Rashtriya Rifles jawan I met at the Delhi airport in 2015.

I was on my way to Jammu and the jawan, possibly in his twenties, was sitting next to me in the plane. We started to converse and that was when I heard his story. He felt envious of the fact that I was living with my family and could air my views without any fear. His own life, he felt, was nothing but miserable. He had recently become a father and was returning to work from his village in Rajasthan.

He told me that his life in the camp in Srinagar, though comfortable in material terms, was not worth living. We are in an enemy territory. The locals are not with us, and no matter what we do, kill or love, they are not going to be with us. We are told that we should do this for our tiranga (national flag), so I do it, but at what cost? I am away from my wife, my parents and child, trying to hold on to a place which we all know is not with us. I dont understand politics. I am doing this job for a living and wish all this could be solved so that I can be closer to home.

Home

Even today, 200 Magazine House, Karan Nagar, Srinagar, is not a mere memory to be recreated through words or seen in dreams. It is a place where I formed my first impressions of the world, cocooned as I was in the care of my parents. Life then was like drawing lines on a blank sheet of paper.