PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA

Copyright 2015 Peter Kavanagh

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published in 2015 by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, a Penguin Random House Company. Distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

Knopf Canada and colophon are registered trademarks.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Kavanagh, Peter, 1953, author

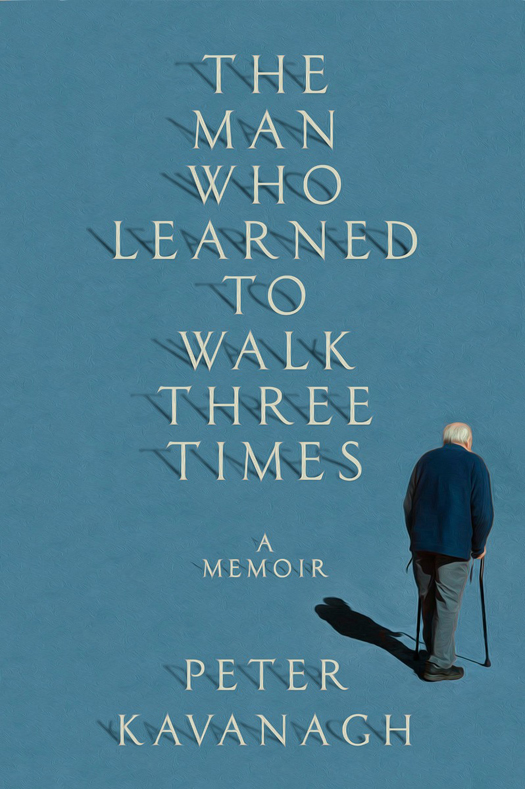

The man who learned to walk three times : a memoir / Peter Kavanagh.

ISBN 978-0-345-80852-3

eBook ISBN 978-0-345-80854-7

1. Kavanagh, Peter, 1953Health. 2. Kavanagh, Peter, 1953. 3. PoliomyelitisPsychological aspects. 4. PoliomyelitisPatientsRehabilitationCanada. 5. PoliomyelitisPatientsCanadaBiography. 6. JournalistsCanadaBiography.

I. Title.

RC181.C2K39 2015 362.1968350092 C2014-906375-X

Family snapshots courtesy of the author.

Cover photo and all other photos by Debi Goodwin.

Interior images: (cane and crutches) Dece11 / Dreamstime.com

v3.1

For my parents,

who were there for the first two times

I learned to walk but missed the third.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

I n September 2013, I travelled to Italy. Within an hour of arriving, I was climbing up old marble steps that had become pitted and worn over the centuries. Using my cane and an iron handrail bolted into the wall, I found a spot on the uneven and slippery surface where I could position myself to move my right leg to the next step, and then my left. There were two flights of fifteen steps each between the courtyard of the ancient building in Romes Jewish ghetto and the landing leading to the apartment wed rented. Going up, I would stop at each step, take a breath and think about how to position myself so as to step up most efficiently, with the emphasis on moving my body primarily through my legs. Going down, I would stop, take a breath and calculate how best to position myself so as to step down without falling while at the same time moving as quickly as possible. Going up and going down, I would feel a certain self-mocking frustration. The only thing that irritated me more than these stairs was trying to sort through the set of five keys necessary to unlock the various doors between the street and our temporary home.

Several times a day for the next four days, that was the routine. It wore out my body, worried at my mind and oddly exhilarated me. I was petrified that I would lose my footing, fall and injure myself, and ultimately become even more of a burden than I already was. I was equally certain that everyone was watching me and laughing at my clear ineptitude at this most basic of tasks.

At the same time, I wanted and needed to do this trip. When I booked the apartment, I had no idea about the stairs and what simply going in and out might entail, and when I first saw the steps I felt a momentary panic but then kept going. This is what people dostruggle with difficulty and move on. I was thinking, if I can do this, even clumsily and with great effort, what else can I do?

The next several weeks in Italy were filled with cobblestone, uneven pavement and sloping piazzas. Sometimes I could not surmount these challenges. Other times, obstacles that would have paralyzed me into inaction even six months earlier seemed like nothing.

For three weeks, I walked up and down slopes that terrified me; worked muscles, tendons and joints in ways they had never been worked before; experienced new types of pain and fatigue; and thought about the walking I had just done, the walking I would do tomorrow and whether I would ever be able to stop thinking about walking.

Walking is the key to who I am.

How I walk today, the canes and walking sticks I have owned, the braces I have worn and wear, the shoes I cant buy, the shoes I can, how I think about my walking, how other people think of my walkingall have been ravelled together and constitute the heart of me.

My earliest memories, stark images of figures in masks wrapping me in restrictive cloth; my recent dreams of moving, being unable to move, of standing and falling (varying in frequency, detail, and degree of terror and joy); my most common flashbacks; my aversion to mirrors and plate glass windows; my formerly constant speculating about how people perceived my limpthis entire maze and mess of interior dialogue is the cause and consequence of a lifelong and unusual attention to walking. And a lifelong attention to walking is not normal.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines walking as mov[ing] at a regular pace by lifting and setting down each foot in turn, never having both feet off the ground at once. Seems simple, even straightforward. The OED could have gone on to note that walking is one of the key unconscious activities that human beings do. We learn how to walk and then simply do it, with little thought. K.H. Thomann, a renowned expert in normal and abnormal walking, wrote, For most people, walking is an automatic, unconscious activity, characteristic of each individual. Most parents who watch an infant beginning to walk realize that locomotion is a highly complex, learned process. Years of training and practice are necessary for the sensory-motor system to become adept at automatically generating the motor commands necessary to permit walking without conscious effort.

Saint Denis, the patron saint of walkers, was killed in 250 CE by beheading. The story goes that he then picked up his head and carried it for almost ten kilometres, preaching all the way. The legend displays an essential understanding of the science and practice of walking, which is much more about tissue, nerve, muscle, tendon, habit and experience than it is about conscious thought. Putting aside the question of the miraculous, if you can deliver a sermon while carrying your own head and walking, then clearly the power of unconscious activities enables and supports the most basic of human multi-tasking.

On that trip to Italy, which was both a holiday and an experiment, the constant attention I paid to my walking caused every muscle to tense up and, over the course of a day, wore me out mentally and physically. I was the guy who slowed traffic and disrupted the flow of pedestrians. I cant count the number of vistas, odd occurrences and magnificent buildings and sculptures that I missed because I was concentrating on navigating a particular piece of cobblestone or a missing piece of pavement.

Getting walking right is learning not to think about it. That is almost the definition of what it means to learn to walk. It is a lesson I have learned three times.