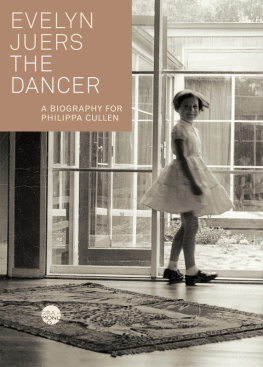

THE

DANCER

Also by Evelyn Juers

House of Exile

The Recluse

EVELYN

JUERS

THE

DANCER

A BIOGRAPHY FOR PHILIPPA CULLEN

First published 2021

from the Writing and Society Research Centre

at Western Sydney University

by the Giramondo Publishing Company

PO Box 752

Artarmon NSW 1570 Australia

www.giramondopublishing.com

Evelyn Juers 2021

Designed by Jenny Grigg

Typeset by Andrew Davies

in 9/15pt Tiempos Regular

Author photo: Sally McInerney

Printed and bound by Ligare Book Printers

Distributed in Australia by NewSouth Books

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia.

ISBN: 978-1-925818-72-7

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Giramondo Publishing Company acknowledges the support of Western Sydney University in the implementation of its book publishing program.

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

Contents

Prologue

The struggle for solitude and peace is more difficult for a woman, than a man. People do not expect a woman to like solitude, and they continually intrude. So I keep moving on.

Philippa Cullen, 1972

Dance is awareness of movement.

Philippa Cullen, 1972

There ought to be a book written about me, that there ought! And when I grow up, Ill write one but Im grown up now, she added in a sorrowful tone: at least theres no room to grow up any more here.

Lewis Carroll, Alices Adventures in Wonderland

Though I did not know her name, in the 1960s I sometimes saw Philippa Cullen in the Reading Room of the Mitchell Library at the State Library of NSW. We were two teenage girls working on school assignments. A few years later I caught sight of her again at Sydney University, in lectures or weaving through a crowd on Science Road, Glebe Point Road, King Street. She walked buoyantly, her ponytail swinging from side to side.

Someone said: Thats Philippa, the dancer.

We met in 1971 on one of the higher floors of the new copper-and bronze-clad reinforced-concrete stacks of the universitys Fisher Library. I now wonder what I was looking for with such zeal when I riffled through the card catalogues and surveyed the shelves laden with history and literature, esoterica, miscellanea, in my early twenties in the early 70s. Most days I would gleefully bring back a treasure of new and old books, the older the better, to one of the small desks along the southern wall of the stacks where windows like arrowslits let in fractions of daylight and, looking outwards, offered slim views of the world below. At those monastic desks students composed essays, checked their timetables and finances, circled job ads or rooms-for-rent, in biro. Possibly more dramatic things happened in that forest of books, a conception, a betrayal, a death. I dont know. I kept a list of what Id read. Certain writers were in the air. The prophets Yeats, Beckett, Lorca, Rilke. The poet Martin Johnston made sure we all knew Ezra Pound. In a seminar a bloke insisted on the brilliance of Winnie-the-Pooh as an anti-war manifesto, in another a bright spark besotted with Dryden spoke in heroic couplets. It took me a long time to read all of Thomas Manns work, and longer to digest it, but it only took forty-eight spellbound hours to read Middlemarch, at home, at bus stops, on park benches, and in the stacks, where that novels final storm approached and thunder and lightning ushered in the moment the heroine began to say what she had been thinking.

At a nearby desk a woman was speaking softly in different voices. She had a slight lisp: hands her a glass of waterwhere are you goingback to the villageis your mother hereyesshe raises her headI am a seagullno, noan actresscould not walk properlyI have changed nowwalking and walkingthinking and thinking

I strained to hear her. Perhaps she was rehearsing a script. Chekhov, I blurted and she popped up above the partition and laughed. It was Philippa, now packing her bag, ready to rush off. She said shed been studying Stanislavski and as an exercise was trying to memorise some plays in their entirety. At first audiences thought Chekhovs Seagull was dull but Stanislavskis production electrified it. I want to work like that, she said, here and everywhere, Im going overseas, to Europe and Asia, AfricaAmericaI just have to figure out how, if Im lucky Ill get a grant. She glanced at my watch. Late for a rehearsal, better be off. Shed heard that in Europe everyone shakes hands all the time. Hello. Goodbye. So we shook hands. From then on a strong handshake became our jokey greeting or farewell.

After graduation I moved to England to continue my studies. Philippa got her grant, and had been developing her dance ideas in Germany and Holland, when she visited me in 1973. She hated London. And so I chose some short walks to show her parts of the city that might change her mind. We walked from Hampstead Heath to Keats House. And from the ICA on the Mall, where she had an appointment, via Mary Le Strand Church to Australia House, where she had some documents to collect. These strolls did not cover much ground but were extended in space the city, the river and in time, as we talked and she told me about her adventures since leaving Australia. While she talked she sometimes swung around, emphatically, and continued walking backwards on the edge of the curb, like a tightrope dancer. Once it looked like she was going to trip and a car swerved to avoid her. I was alarmed. She said she thought shed die young and if that happened, Id have to write something. And that shed do the same for me. I shrugged it off. In the 70s people talked about destiny and divination, they consulted the I Ching, read palms and tea leaves and tarots. They said things like that. But Philippa knitted her brow, she looked stern. A handshake. Perhaps (I later thought) a kind of pledge.

That summer, before flying off to study music and movement in Ghana, she left her theremin and other belongings with us in Greencroft Gardens. Brochures on walking, in England and Ireland, some maps, a book on phenomenology. Her books, including the ones she borrowed and returned, always had a leaf pressed between the pages.

I saw her again in the autumn when she came to pick up her things and I suggested a traverse of London. Wed meet at a pub called The Sun in Splendour, walk along Portobello Road, cross Kensington Gardens and end at the Victoria and Albert Museum to see The Floating World exhibition. Or, she said, we can visit the poor old dodo at the Natural History Museum.

She was named after her grandfather Philip Buckland who had fought at Gallipoli. And Dodo was what she fondly called her grandmother Kate. She told me that when she was little her mother took her to the dawn service on ANZAC Day. They laid out their clothes the night before and left home in the dark. She loved the bands and marching and solemnity. The drum beat. She wanted to learn drumming.

See you at The Sun in Splendour! But that walk never happened. She had had enough of Europe and was heading home via Nepal and India. I wasnt a great letter-writer and we corresponded infrequently; I was sure wed meet again and would continue our conversations, wherever.

Next page