Blink of an Eye

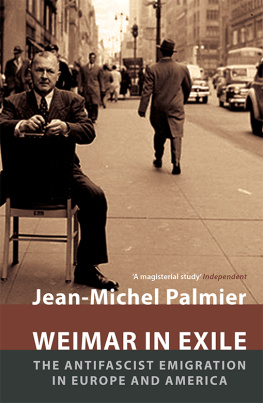

Approaching from a distance, hand in hand like lovers, the tall blonde and the old gentleman both called out to him Brecht! He turned towards them and waved. The Californian sun glinted from his glasses like the sword of Zorro. It was early morning. Heat and the scent of jasmine hung loosely all about the market-place. Sunlight played upon the unreal splendour of the fruit and vegetables. Not quite real. Some people claimed the produce of this country lacked character, it always looked much more promising, bigger, brighter, than it tasted. Especially apples. They complained that there were certain things gooseberries, for instance which you could not get at all. Asparagus only came in cans. And who had been able to buy chanterelles since theyd left Europe? On this day in the summer of 1944, just before the German generals attempt on Hitlers life, the news had sped like wildfire through the community of European exiles in Los Angeles that a farmer from the north was selling berries at the market. Not just strawberries, blueberries, raspberries, blackberries, there was also a small supply of gooseberries. At the head of a line of people anxiously waiting to be served, Bertolt Brecht chewed on his El Capitn Corona. Fond of sayings and slogans, he proclaimed that the early bird catches the vorm , and money talks, and proceeded to buy up all the golden berries. Oh yes, they were ripe enough to eat. Striding across the plaza towards Nelly and Heinrich, he stopped here and there to divide the loot, handing Gnsebeeren , as he jokingly translated from the English, to friends who had missed out.Ah, here comes the man who loves gooseberries, someone said in a heavy accent, referring to one of Chekhovs stories, casually, as if Russian classics were still common currency, as if Brecht had just crossed Berlins Savignyplatz and was offering summer berries from a cone-shaped paper bag. Finally he scooped a great mound of amber fruit into Nellys basket. He gave them each, Heinrich and Nelly, a translucent gem to taste.One for Adam and one for Eve, he chuckled. The proof of the pudding. And crushing a berry against his own palate like an oyster, announced triumphantly that it was delicious, the real thing, not a hybrid, and that he was no gooseberry fool.

It could have happened.

It had to happen.

It happened earlier. Later.

Nearer. Farther off.

It happened, but not to you.

WISLAWA SZYMBORSKA, COULD HAVE

Several months later, on Sunday 17 December 1944, at home at 301 South Swall Drive, Los Angeles, in the not yet broken darkness before dawn, the outline of a bowl of fruit on the windowsill, its curves a hand of bananas Nelly had bought earlier in the week, grapes, some pears reminded Heinrich of Brechts generosity and of their animated exchange that day at the market, when theyd all had new information about friends in trouble, jailed, people killed, and shocking rumours of the progress of the war. Oh the terrible disgrace! Theyd switched between languages, Stachelbeeren , Stacheldraht , Stacheln , barbs.Barbarians! Brecht had exclaimed. But that moment, which Heinrich tried to conjure up, now faded.

It left nothing before his eyes but a silhouette of fruit backlit by a gauze of curtains, grey on grey. He was a very old man shrinking from the night, from this terrible night, the worst night of his life.

He was no longer sobbing uncontrollably. He felt numb. Unable to focus. Did he doze? Briefly? Perhaps he was dying? His only physical sensation came from the bridge of his spectacles pressing on his nose. He made himself take them off, and rubbed his eyes. Did he then recall or did he dream? That when they were children his brother had once worn a peg on his nose for a whole day, until a blockage in the plumbing was fixed and the stench the household had to endure was gone.

Heinrich sat very still inside the folds of his suit. Inside the immaculate whiteness of his long-sleeved shirt. His wife had washed it, hung it out, brought it in, ironed it as he watched her through the open door, and placed it on a hanger, smoothing it with the flat of her hand, tugging each cuff into shape. This image and the thought of her absence was too much to bear. He was crushed with grief. He sat deep inside the maculations of his own soft skin and felt minuscule. Like a grain of sand. His mind searched for a place to go, where it could escape.

In Lbeck. In summer. In the garden. In the scented air. Where it was warm and still. A red dragonfly Sympetrum vulgatum , the vagrant darter, how strange to remember it hovered over the fountain like a hawk. Dragonflies fed on mosquitoes; mated in the air; this one settled for a moment on the leaf-blade of a stand of purple irises. Blackcurrant and prickly gooseberry bushes grew against the garden wall. He sat in the shade of the walnut tree. From an open door someone called his name.Children, how far did we get with this? he heard his mother ask.

A change in the weather. A wind came up, and suddenly clouds like great grey waves were being swept along. The boy looked up, following their crazy script. Just then a grain blew into his eye and he rubbed the irritation with his fist until the billowing sheet of sky that hed been watching flashed red from too much rubbing, and his eye burned with pain. He took up his pencils, blindly, and the sketches hed made. With one lid shut, the other squinting sympathetically, he felt his way along the wall until he reached the door.

The old man did not want to enter. He knew that there was no going back. For one thing, this house at Beckergrube 52 no longer existed, it had been destroyed during the British raid in 1942.

Lbeck, a member of the once significant Hanseatic league of Baltic ports, lies on a low-crested island between the rivers Waken-itz and Trave. Even in the long decline since its peak of power in the fourteenth century, with its trademark late-Gothic gateway, the Holstentor, and the towers of St Aegedien, St Jakobi, St Katharinen, St Marien, St Petri, and the Dom, rising above step-gabled merchant-houses that line narrow streets and foreshores, the town always retained the demeanour of an independent trading centre. During the night of 2829 March 1942, by the light of a nearly full moon, deemed excellent visibility , more than half of Lbecks buildings were destroyed and hundreds of people killed and injured; 234 aircraft had split into three waves of attack to drop more than 400 tons of bombs. In retaliation, it is said, the Germans opened a Baedeker tourist guide to England, selected several sites of historic significance, and bombed Bath, Exeter, Canterbury, York and Norwich.

But of course, innocent of what the old man knew, the boy had already gone into the house, there was no stopping him. He was splashing his face with water, telling his sisters no, no, that he hadnt been crying, that it was just a bit of dirt. And so the old man followed his childhood self, unseen.

How far did we get? their mother asked again. On sofas and chairs they sat in an attentive circle, while she opened a volume, resting it on the lid of her desk. To read to them, she often stood up, and so it almost seemed like a sermon in church, or a lesson in school. It might have been in the early summer of 1886, when he, Heinrich, was aged fifteen, Thomas (whom they called Tommy) was eleven, Julia (called Lula) was nine, and Carla, sitting close to her eldest brother, was only four years old. Always inclined to theatrical pranks and gestures, they had picked flowers that morning and had assembled for the reading, with Carla wearing an extravagant crown of pansies. Tommy had plaited it, Lula had pinned it to her sisters curls. Now they waited in mischievous silence, until their mother looked up from leafing through the book and broke into a smile.Ah yes, she said. Here we are she wore a little wreath of pansies .