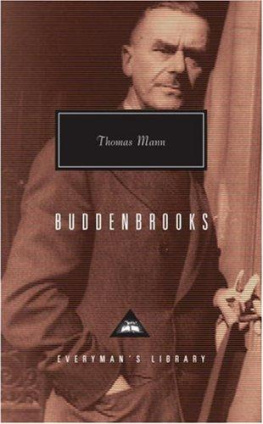

THOMAS MANN (18751955) was born in Lbeck, Germany. His father was the heir to a wealthy merchant family; his mothers ancestry was German, Brazilian, and Portuguese. Mann, a poor student with little patience for school, was slated to go into the family business, but his fathers early death led to its liquidation, and the family moved to Munich, where Thomas and his elder brother Heinrich both began their literary careers. Published in 1901, Thomass first novel, Buddenbrooks: The Decline of a Family, became a great success, and in 1905, Mann married Katia Pringsheim, the daughter of prominent German Jewish intellectuals and a member of one of Germanys richest families. The two had six children, among them the novelist Klaus, the historian Golo, the scholar Michael, and the journalist and political activist Erika. Manns second novel, Royal Highness, was followed by a number of shorter works, including, in 1912, the novella Death in Venice, which confirmed his reputation as a major contemporary writer. During World War I, Mann ardently supported the German cause, leading to a rupture with Heinrich, a vocal antinationalist. In 1918, with the war effectively lost for Germany, Mann published Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, in which he connects his defense of Germany to his dispute with his brother. In the years after the war, the brothers reconciled, while Thomass political leanings gradually shifted left. In 1924, Mann published The Magic Mountain; five years later, he received the Nobel Prize in Literature. Upon Hitlers rise to power in 1933, he fled to Switzerland. The outbreak of World War II took him to California, where he gave broadcasts in opposition to the Nazis and completed his last major works, the tetralogy Joseph and His Brothers and the novel Doctor Faustus. Mann left the United States in 1952 and spent his last years in Switzerland, where he is buried.

REFLECTIONS OF A NONPOLITICAL MAN

THOMAS MANN

Translated from the German by

WALTER D. MORRIS

and others

Introduction by

MARK LILLA

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Introduction copyright 2021 Mark Lilla

Translation of Reflections of a Nonpolitical Mancopyright 1983 by Walter D. Morris

Translation of Thoughts in Wartime copyright 2021 by Cosima Mattner and Mark Lilla

Translation of On the German Republic copyright 2007 by Lawrence Rainey

All rights reserved.

Published in German as Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen, Gedanken im Kriege, and Von deutscher Republik

Cover image: Romain Thiery, Requiem for Pianos 33, 2018; courtesy of the artist

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mann, Thomas, 18751955, author. | Morris, Walter D. (Walter Duff), 1929, translator. | Lilla, Mark, writer of introduction.

Title: Reflections of a nonpolitical man / Thomas Mann ; translated by Walter D. Morris ; introduction by Mark Lilla.

Other titles: Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen. English

Description: New York City : New York Review Books, 2021. | Series: New York Review Books classics

Identifiers: LCCN 2020013687 (print) | LCCN 2020013688 (ebook) | ISBN 9781681375311 (paperback) | ISBN 9781681375328 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Mann, Thomas, 18751955Political and social views. | GermanyPolitics and government19181933. | World War, 19141918Influence.

Classification: LCC PT2625.A44 B513 2021 (print) | LCC PT2625.A44 (ebook) | DDC 833/.912dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020013687

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020013688

ISBN 978-1-68137-532-8

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

(1918)

Translated by Mark Lilla and Cosima Mattner

Translated by Lawrence Rainey

INTRODUCTION

I want to say everythingthat is the purpose of this book.

Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man

On Friday, August 4, 1914, German troops invaded neutral Belgium, and by days end Britain and Germany were at war. The following Monday, in an otherwise perfunctory letter to his brother Heinrich, Thomas Mann made an uncharacteristic confession:

I still feel as if Im dreaming.... What a visitation! What will Europe look like after, inwardly and outwardly, when it is over?... It is fairly certain that if the war lasts long, I shall be what is called ruined. So be it! What would that signify compared with the upheavals, especially the large-scale psychic upheavals which war must necessarily bring? Shouldnt we be grateful for the totally unexpected chance to experience such mighty things? My chief feeling is of tremendous curiosityand, I admit, the deepest sympathy for this execrated, indecipherable, fateful Germany.

Mann was thirty-nine years old at the time and a well-regarded writer. His first novel, Buddenbrooks, published in 1901 when he was only twenty-six, had made him famous throughout Europe and would earn him the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1929. Though he would not write another novel for two decades, his short stories and novellas, including Death in Venice (1912), kept him at the center of literary attention. Mann was a respected member of the German cultural establishment in Munich, where he lived. He attended concerts, he befriended composers, he read Goethe, he sent his children to the Volksschule, and he never expressed any views about politics. He was, as he would wryly put it, a good German burgher.

All that changed in 1914. Why is anyones guessit was as if some inner diabolus had been released. From one month to the next he became an intransigent and inflammatory defender of the German cause on the international stage, writing articles and giving speeches that made him a favorite on the vlkisch nationalist right. The war dragged on, and as it did he put aside his literary projects to devote himself entirely to a defense of Germany against the onslaught of alien Western ideas of enlightenment and democracy. He did not finish Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man until early 1918, when Germany was about to launch its last, doomed military offensive. The book arrived in bookshops in October, a few weeks before the armistice was signed, an untimely birth.

If Thomas Mann thought that Reflections would mark an escape from politics, he was very much mistaken. Politics was not done with him and never would be. Postwar Germany plunged into economic uncertainty and political chaos, as violent right- and left-wing radicals turned on each other and tried to bring down the young Weimar Republic. This crisis finally compelled Mann to distance himself from many of the views he expressed in Reflections. In 1930, after the National Socialists won a disturbingly large number of seats in parliamenta storm warning, he called ithe delivered a brave, unambiguous address titled An Appeal to Reason that exposed the fanatical reactionary state of mind behind Nazism: Fanaticism turns into a means of salvation, enthusiasm into epileptic ecstasy, politics become an opiate for the masses, a proletarian eschatology; and reason veils her face. Soon he was a marked man.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, Mann was on a European tour lecturing on Wagner and within days family and friends were urging him not to return to Munich. He never did. After a brief hiatus in France he spent the next five years in Switzerland and, in 1938, settled in the United States, first in Princeton and then in Los Angeles. In these years he became a major voice in the migr intellectual community and argued relentlessly against the appeasement and isolationism of Western democracies. When war finally came, he made prodemocratic propaganda speeches around the United States and delivered regular German-language broadcasts that were transmitted into his former homeland. He received many honors, met with President Roosevelt, and became a US citizen in 1944.