INTRODUCTION

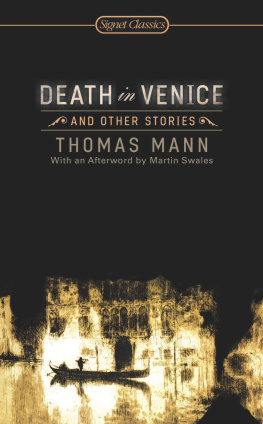

T HE PRESENT selection of Thomas Manns stories represents a period in his work of about twenty years, from his literary beginnings to just before the First World War. This period contains at its end his greatest story, Death in Venice (1912, first book edition 1913), and also, near its beginning, his first and (as many would still say) greatest novel, The Buddenbrooks (1901). The other stories here selected all belong to the turn of the century, when Mann (born in 1875) was in his twenties; two were published a few years before The Buddenbrooks, the rest shortly after it. Mann is generally thought of as a novelist rather than as a writer of short stories (or Novellen, as they are usually called in German), and his total output of about thirty stories is quantitatively only a small fraction of his output of major novels. Mann himself, however, was not convinced that the major fictional form was really more suited to his characteristic talent than the short story. Late in his life, when working on Doctor Faustus (1947), he wondered, rather overdespondently, whether he would ever be able to write a better novel than his first, which had almost at once established his national fame and twenty-eight years later won him the Nobel prize. He always felt more confident, however, about the value of his short stories, stating more than once that this more succinct form, which he had learned from Maupassant and Chekhov and Turgenev, was his own genre; and critical opinion in the thirty-three years since his death has tended to bear this out. His novels fill seven volumes of his collected writings, his stories only one; but in it are several acknowledged masterpieces of European short fiction, and Death in Venice in particular bids fair for recognition as the most artistically perfect and subtle of all his works. The short story was a form to which he kept returning between ambitious novel plans, not all of which were realized; and it is significant as well as surprising that all his major novels, from The Buddenbrooks to Doctor Faustus (as well as the long picaresque fragment Felix Krull, begun in 1910 and finally reaching the end of only its first volume in 1953) were originally conceived as short or long-short stories.

Mann was a prolific critic, essayist, and letter writer, and among his many comments on himself and his own work is one, also made in later life, that applies particularly clearly to these prewar stories, though it applies to The Buddenbrooks and most of the other novels as well. In his autobiographical essay A Sketch of My Life, looking back in 1930 at what was by then the greater part of his literary output, he remarked that each of a writers works is a kind of exteriorization,

a realization, fragmentary to be sure but self-contained, of our own nature, and by so realizing it we make discoveries about it; it is a laborious way, but our only way of doing so.

And he added: No wonder these discoveries sometimes surprise us. This has been recognized as an unmistakable echo of Goethes much-quoted observation (also made in middle life) that all his works were fragments of a great confession; and although Manns is a modern, more complicated, psychologically colored version of the point, it remains an irresistible invitation to us to see his works, like Goethes, as among many other things a series of exercises in more or less latent autobiography. The fact that so many critics have insisted on this view of them, apparently with authorial blessing and often to the point of tedium, does not mean that we can or should wholly eschew the biographical or psychographical approach, which at one level is a necessary part of the commonplace of general information about both Goethe and Mann. Mann transmuted his personal substance into art with a great deal more self-conscious irony than did Goethe (and irony is another word which, despite its endless reiteration, is impossible to avoid when discussing him); but he was not engaged merely in an introspective or literary game. It was more like a serious process of self-discovery and practical self-analysis, of fictional experimentation with actual or potential selves and actual or potential intellectual attitudes. Despite the cynical mask he often wore, especially in his early years, it was ultimately a quest, a search for some kind of balance and wholeness, for human values that would (by reason of that very balance) be personally sustaining as well as intellectually satisfying and positively related to the culture of his times. In most, perhaps all, of the stories here presented we can observe, deeply disguised though it may be, this process of self-educative experimentation.

Something like it is certainly happening in The Buddenbrooks, which stands as a monumental and dominating feature in the background of the first six of these early stories. At one level it was a vast mirror in which Manns German public recognized itself, an ironic yet not hostile study of North German middle-class life; but it is far more than a social novel. It is autobiographical in the sense that Mann was here exploring his own origins, the roots of his personality and talent as they were to be found in his family and immediate forebears. Artistically the novel is a masterpiece, but as its subtitle, Decline of a Family, might suggest, the exploration yielded a bleak message. The two characters most closely identifiable with aspects of Mann himself, Thomas Buddenbrook and his son Hanno, who represent the last two Buddenbrook generations, both die (one in his forties, one in adolescence) for no other very good reason than that they have lost their will to live. The positive and humane values embodied in the traditions of this great Hanseatic trading family seem in the end to be negated. Thomas loses faith in them, and his life becomes a mere exhausting keeping up of appearances; the inward-looking, sensitive Hanno never had any faith in them anyway, and solves his existential problem by succumbing to typhus when he is about fourteen. In the closing pages the surviving womenfolk sit round like a naturalistic Greek chorus, trying not to doubt the Christian message of a reunion in the hereafter. Despite the great zest and comic verve with which the detailed substance of the story is presented, The Buddenbrooks in the general tendency of its thought may be described (using here another unavoidable word) as an exercise in nihilism.

Thomas Mann himself clung to no kind of Christian faith. His intellectual mentors were Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, particularly the latter, whom he read avidly from an early age; the former he did not encounter at first hand until he was well on the way to completing The Buddenbrooks, but from Nietzsches writings he could have absorbed much of the Schopenhauerian message. Schopenhauer, the supreme exponent and stylist of philosophic pessimism, had published his masterpiece The World as Will and Idea as far back as 1818; unrecognized at the time, it had become increasingly influential in the later nineteenth century. It offered an atheistic but metaphysical system, beautifully elaborated into a symphony of concepts, founded not only on a deep and imaginative appreciation of the arts (and of music above all, the art Mann most deeply loved), but first and foremost on a rage of compassion for the suffering of the human and animal worlds. Schopenhauer regarded any kind of optimistic philosophy as not merely stupid but actually wicked, an insult to the immeasurable pain of all sentient creatures. In his own later essay on him (1938) Mann remarked on the strangely satisfying rather than depressing character of this great protest of the human spirit: for when a critical intellect and great writer speaks of the general suffering of the world, he speaks of yours and mine as well, and with a sense almost of triumph we feel ourselves all avenged by his splendid words. The young Thomas Mann, especially, seems to have agreed with Flaubert (and with his own Tonio Krger) that to write was to avenge oneself on life. Art was redemptive and, so to speak, punitive. That at least was Manns theoretical and deeply temperamental starting point: a vision, as he was to put it in Tonio Krger, of comedy and wretchedness. It is part of the essential theme of The Buddenbrooks that in proportion as the family loses its nerve its later members become more intellectually sensitized and inward-looking, they participate more deeply in this negative vision. The two processes, culminating in Hanno, are aspects of one and the same decline.