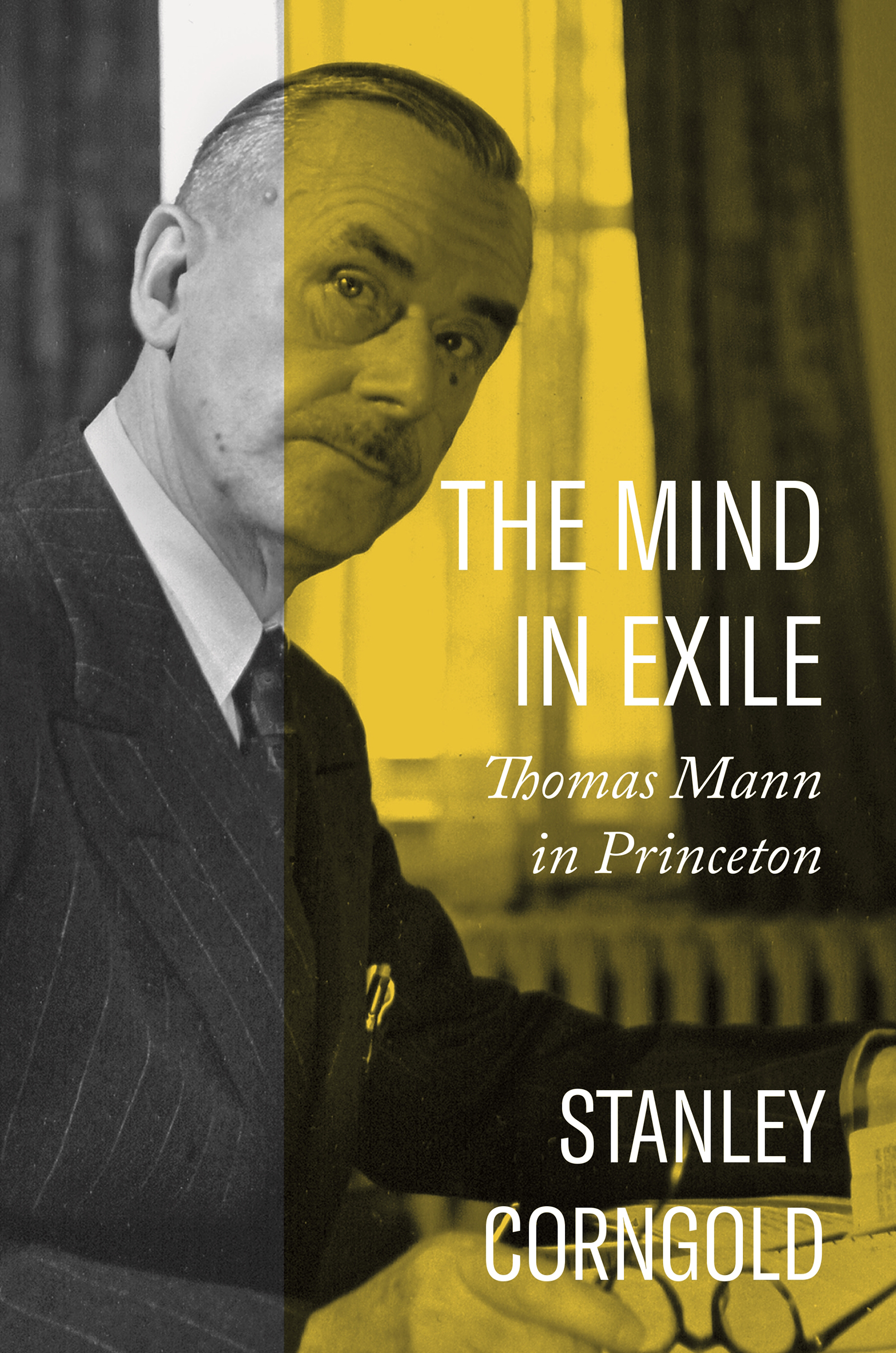

THE MIND IN EXILE

The Mind in Exile

THOMAS MANN IN PRINCETON

STANLEY CORNGOLD

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2022 by Stanley Corngold

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Corngold, Stanley, author.

Title: The mind in exile : Thomas Mann in Princeton / Stanley Corngold.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021018405 (print) | LCCN 2021018406 (ebook) | ISBN 9780691201641 (hardback) | ISBN 9780691229676 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Mann, Thomas, 18751955ExileUnited States. | Mann, Thomas, 18751955Political and social views. | Mann, Thomas, 18751955Homes and hauntsNew JerseyPrinceton | Mann, Thomas, 18751955Friends and associates. | Princeton (N.J.)Intellectual life. | Authors, German20th centuryBiography.

Classification: LCC PT2625.A44 Z544197 2022 (print) | LCC PT2625.A44 (ebook) | DDC 833/.912 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021018405

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021018406

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Rob Tempio, Matt Rohal, and Chloe Coy

Production Editorial: Mark Bellis

Jacket Design: Layla Mac Rory

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: Alyssa Sanford and Carmen Jimenez

Copyeditor: Jodi Beder

Jacket photo by Fred Stein fredstein.com

CONTENTS

- vii

- xix

PREFACE

THIS BOOK DESCRIBES the extraordinary exile of the German writer Thomas Mann in Princeton, New Jersey, where he lived for two and a half years, from September 1938 to March 1941. They frame a crucial historical juncture, the beginning of World War II, spanning the Nazi dismemberment of Czechoslovakia and the intensified bombing of England.

Mann arrived in Princeton as the widely praised author of the novels Buddenbrooks, the Decline of a Family, for which, in 1929, he received the Nobel Prize, and The Magic Mountain, on which many a young reader has cut his or her intellectual teeth; and the great novellas Tonio Krger and Death in Venice. It might be enough to say at this point that his first novel and stories were loved by Franz Kafka. Along with Albert Einstein (18791955), Mann, who was Einsteins elder by four yearsMann was born in 1875 and died several months after Einstein in August 1955was the most famous of the refugee intellectuals who lived in or near Princeton during these years. They were eminent figures in a circle, broadly speaking, that included Manns best friend, the cultural historian Erich Kahler (18851970); the novelist Hermann Broch (18861951), who was Kahlers best friend; the Princeton University physicist Allen Shenstone (18931980) and his wife Mildred (Molly) (d. 1967), a special favorite of Manns wife Katharina (Katia) Pringsheim Mann (18831980); and solid acquaintances from the Institute for Advanced Study, among them the mathematician Hermann Weyl (18851955), the logician Kurt Gdel (19061978), and Manns translator H[elen]-T[racy] Lowe-Porter (18761963) and her husband, the Russian-American paleographer Elias Avery Lowe (18791969), who also held a post at the Institute. The propinquity of these scholars was at once mental and physical: Hermann Broch lived in Einsteins house for a time and thereafter in Kahlers mansard, where he wrote his towering novel The Death of Virgil. Kahler and Einstein lived only a few streets away from Mann, whose own distinction survives in the unmasterable volume of the work of high quality he produced, let alone the volumes upon volumes of criticism dealing with this work. Toward the end of his life in 1952, Mann wrote to the Yale Germanist Hermann Weigand: Even in these times it is possible for a man to construct out of his life and work a culture, a small cosmos, in which everything is interrelated, which, despite all diversity, forms a complete personal whole, which stands more or less on an equal footing with the great life-syntheses of earlier ages. He was entitled to think that his own achievement had met this standard, and everything he accomplished at Princeton belonged to it.

Manns exile in Princeton lasted until 1941, when he moved to Pacific Palisades, an elegant neighborhood of Los Angeles, attracted by the climate and the presence of even more stimulating refugees, including the movie gang.

At this moment of writing, winter in America, we are subjected to an exercise of power, as once in Manns Germany, by a persistent invocation of crisis. Crisis means things separating, things coming apart, embroiled in perpetual change. Like it or not, we have achieved the ambition of a Faust, who dedicates himself to the turmoil of incessant inner commotion, the most painful excess / enamored hate and quickening distress.

Beset daily through the social media by manifestations of willfulness without circumspection, without prudencewithout grammar!an ongoing sequence of crisesthe frenetic changes of the news cycle, the bewildering storm of disconnected bits of information whose disconnect is importantly owed to an absence of perspective, more precisely, to a dwindling historical memory ofand care forpast experience as a principle of organization, Finally, there is Erich Kahlerclairvoyant in 1961for a last word on crisis and friction: [A] crisis develops through the increasing friction between an elaborately established, less and less flexible and receptive order and the ever growing perpetually onrushing life material. A crisis is [a] final breaking point, the overpowering of the controlling form by the discontinuous multitude of life.

In regard to all former locally or substantively restricted crises,

they lack the present panicky simultaneity and therefore immediate universality and comprehensiveness of crisis, which is mainly due to the technological unification of our world, the rapidity of world-wide communication, the crowding of events and reactions to events. The incessant advances of our technology and science have, moreover, brought about an inner crisis of man, by promoting conformity and standardization, by alienating individuals from each other and from themselves by besetting human consciousness with continuous material changes, by sweeping away traditions and memories and thus endangering personal and communal identity.

And so, I want, as a modest defense, to awaken the memory of several historical junctures, beginning with the decision in 1938 by Thomas Mann (at that time termed the greatest living man of letters) to immigrate and anchor his American exile in Princeton as Lecturer in the Humanities at Princeton University.

For these two and a half years, Mann was astonishingly productive as author, university lecturer, and public intellectual. With Princeton as his home base, he traveled throughout America, delivering countless addresses in defense of humanistic values. His university lectures on Goethe, Freud, and Wagner were each attended by nearly 1,000 auditors.