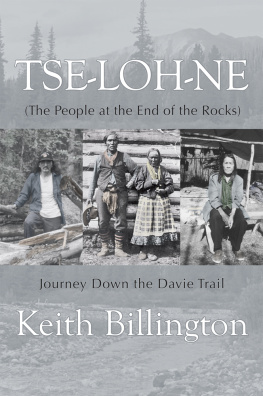

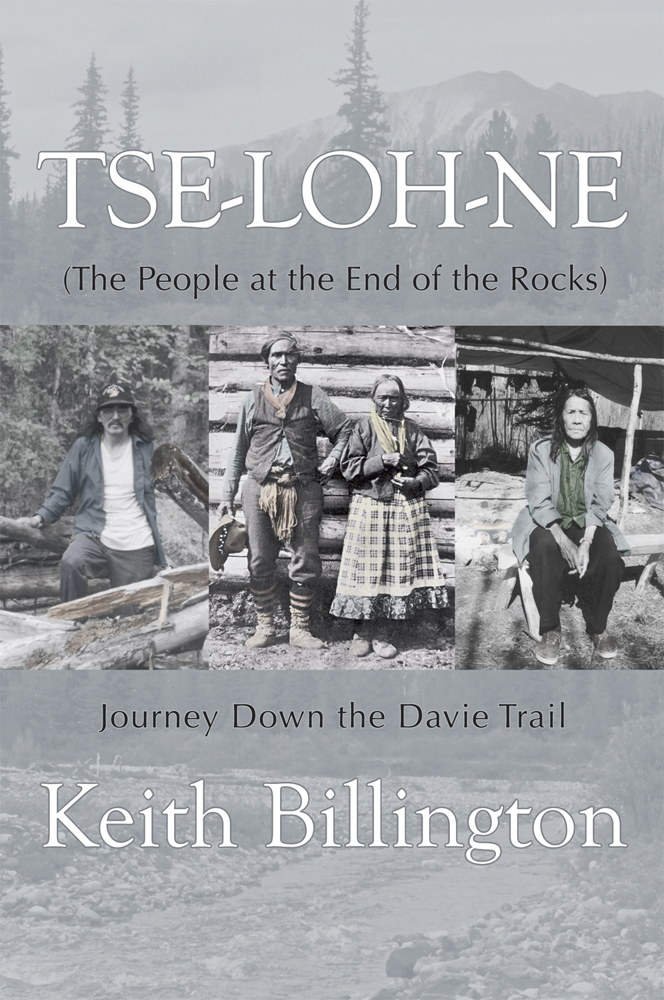

Tse-loh-ne

(The People at the End of the Rocks)

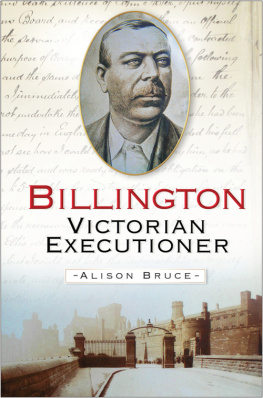

Keith Billington

Copyright 2012 Keith Billington

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency, .

Caitlin Press Inc.

8100 Alderwood Road,

Halfmoon Bay, BC V0N 1Y1

caitlin-press.com

Text design and EPUB by Kathleen Fraser.

Cover design by Vici Johnstone.

Edited by Catherine Edwards.

Caitlin Press Inc. acknowledges financial support from the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of British Columbia through the British Columbia Arts Council and the Book Publishers Tax Credit.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Billington, Keith, 1940

Tse-loh-ne (the people at the end of the rocks) : journey

down the Davie Trail / Keith Billington.

ISBN 978-1-927575-75-8

1. Billington, Keith, 1940. 2. Sekani IndiansSocial life

and customs. 3. Sekani IndiansSocial conditions. 4. Male

nursesBritish ColumbiaFort WareBiography. I. Title.

RT37.B54A3 2012 610.73092 C2012-903333-2

Contents

This book is dedicated to all the elders of Fort Ware who have walked hundreds of miles on trails throughout their homeland. Special thanks go to Charlie and Hazel Boya, Tommy Poole and Chief Emil McCook who shared so many travels and stories with me.

Principal Andreas Rohrbach and the Aatse Davie Education Committee allowed me to copy some of their photographs as did Dennis at W.D. West photographers in Prince George.

Catherine Edwards of UBC has been invaluable for her editorial skills. Thanks to Jay Sherwood for his support and advice.

I could not have written this book without the encouragement and support of my wife, Muriel, who was always there at the end of the trail.

Keith Billington

Prince George, BC

Map by Eric Leinberger.

Introduction

In 1969, Keith Billington and his wife, Muriel, moved to British Columbia from the Northwest Territories, where they had worked as outpost nurses. House Calls by Dogsled (Harbour, 2008) and Cold Land, Warm Hearts (Harbour, 2010) record memoirs of their life and experiences there. In British Columbia, Keith continued working with and for the First Nations of the northern Interior, first working for the Federal Health Services providing remote health care, then later working for the Sekani Band in Fort Ware as the Band Manager.

Keith began working as the Band Manager for the Sekani Band in 1988, at the request of the Fort Ware Chief and Council. Along with his new responsibilities, he found that his past experience and skills were frequently called upon: he did dental work, sutured wounds, delivered babies that couldnt wait, acted as an ambulance driver and prepared deceased persons for burial.

The People at the End of the Rocks describes the lifestyle and history of the Kaska and Sekani people who live in the most isolated village in British Columbia. Through Keiths many adventures, the reader has a glimpse into the hardships and rigours experienced by a people who have one foot in their past and the other foot in the future as they try to adapt to todays values with some reluctance, knowing that change is inevitable.

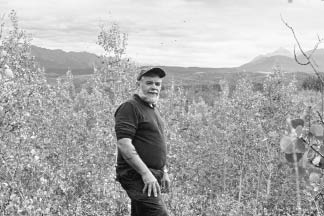

Only 460 kilometres to go, eh? Author Keith Billington on the Aatse Davie Trail.

During a 460-kilometre hike through Kaska and Sekani territory on the Aatse Davie Trail, Keith blends some of the joys and tribulations with stories of the realities of the Sekani life. The People at the End of the Rocks brings together events that have occurred in the past in this wilderness area, which is still on the very frontier of British Columbia, but is now in danger of changing radically as its resources come into demand.

Prologue

A birthday present that almost guarantees that you will lose twenty pounds would delight most people and I was excited to receive such an invitation. The downside of the invitation was the seventy-pound pack I was going to have to carry for 460 kilometres along a little-known trail in the Rocky Mountain Trench.

I had been the Band Manager for the Fort Ware Indian Band for over ten years, and had travelled on the Finlay River by river boat and over many of the local trails by snowshoe, snowmobile, and on skis, but the trail that fascinated me most was the Aatse Davie Trail that ran from Lower Post on the northern border of British Columbia to Fort Ware in north-central BC.

Charlie and Hazel Boya were the only people who were familiar with the trail, having both spent part of their childhoods on the trail and having walked it many times over the years. Now they were talking about hiking the trail again to ensure that it would be part of the Bands land claims strategy when the Band, a member of the Kaska Tribal Council, entered into negotiations with the government.

We have a birthday present for you, Keith, Charlie announced one evening when I was visiting him and his wife, Hazel. Charlie and I had been friends for years and I spent a lot of time at the Boyas house drinking coffee and listening to the tales Charlie told. Charlie knew that I had a great desire to walk the Davie Trail, having heard so much about it from him.

Whats it going to cost me? I asked, knowing that Charlie always had a scheme going that would cost me money.

How would you like to walk down the Davie Trail with us and really experience how we used to live in the bush?

I was delighted and excited at the prospect. I knew that the Kaska were doing everything they could to document their relationship to their land, and that they had negotiated with an environmental group in Williams Lake for Eric Gunderson to do some mapping for them. At the time I didnt mention that my upcoming birthday was going to be my sixtiethit was going to be now or never!

When shall I start packing?

In the Beginning

The Jet Ranger helicopter flew north for two hours along Williston Lake and then up the Finlay River. After sighting a small cabin, the pilot brought the machine down from three thousand feet, banked to the right, and descended with the nose tilted slightly up to a landing on the riverbank. The downdraft from the huge rotors whisked leaves and debris into the fast-flowing river. A few dogs tied up behind the cabin took refuge in their broken-down boxes and then, as the noise and motion slowed down, a man peered out of the cabin door and walked slowly towards us.

He was a tall, lean, angular man dressed in blue jeans and a black western shirt. His shoulder-length black hair was crowned with a black cowboy hat. He smiled and walked over and greeted me, shaking my hand in the brief handshake used by most First Nations people. He told me that his name was Emil McCook and that he was the Chief of the Fort Ware Indian Band.