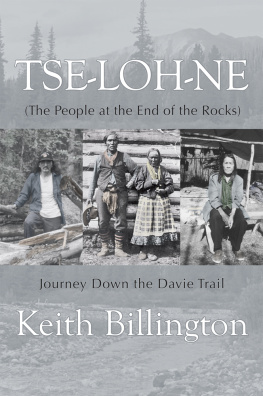

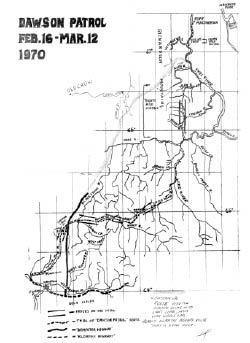

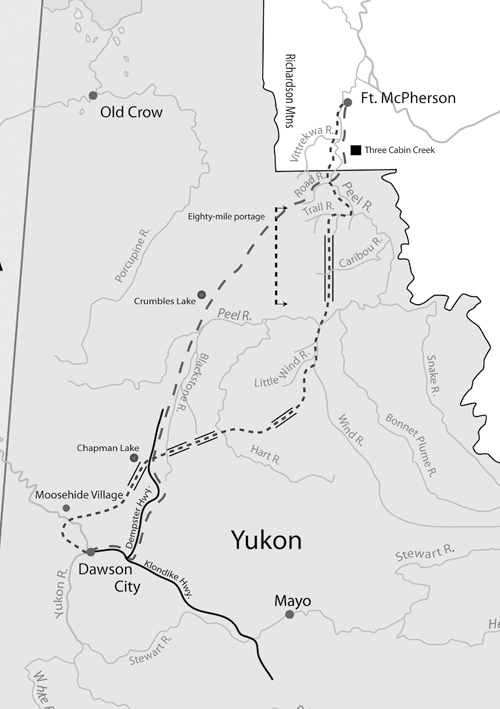

Centennial Project of Fort McPherson, 1970 route map. City of Dawson commemorative brochure.

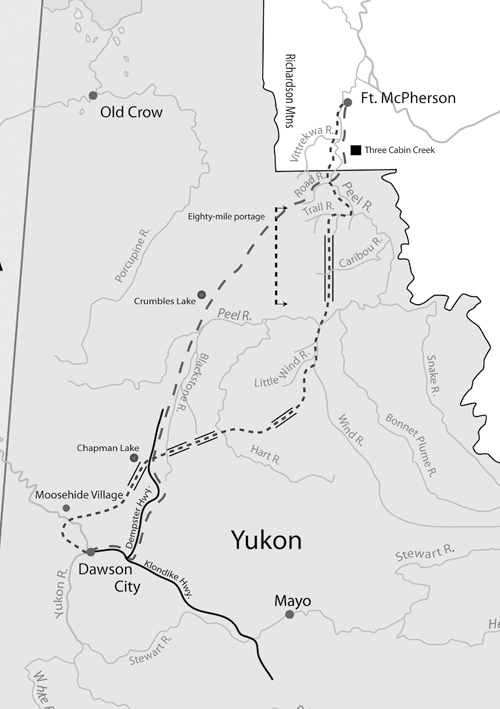

The RNWMP route (short dashes) and the 1970 commemorative route (long dashes).

Introduction

The North has a special appeal for me because back in the 1960s I lived for six years in Fort McPherson in the Mackenzie Delta with my wife and two children, and during that time the Gwichin people who live there endeared themselves to us. They have survived for thousands of years amid the rivers, lakes and mountains of an area that most people would find beautiful but inhospitable, especially in the winter, when blizzards, high winds, freezing temperatures and deep snows sweep over the land. I learned about their way of life when, as an outpost nurse, I travelled by dog team to their muskrat trapping camps and their caribou meat camps in the Richardson Mountains, and a number of times my wife, who is a nurse-midwife, and I camped, along with our young children, with the Gwichin at their winter camps.

But it was while travelling by boat on the Peel River that we came upon a plaque on the riverbank marking the site where, in March 1911, searchers found the bodies of two of the men of the Royal Northwest Mounted Police Lost Patrol. They had died of starvation and exposure while trying to return to Fort McPherson after an unsuccessful dog-team patrol that should have ended in Dawson City in the Yukon. A few miles upstream there was another plaque marking the spot where two more of the patrols members died. The story of this Lost Patrol made world headlines in 1911, and as I stood looking at that plaque fifty years later it captured my imagination, too.

The indomitable spirit of such men has always intrigued me, and the question that often arises in my mind is: How would I have acted in the same circumstances? And I can feel the challenge rise within me. But Inspector Frances J. Fitzgerald, who led the Lost Patrol, was a leader of men. Im not. Im usually a follower, though when an occasion for adventure presents itself, I have tried to take advantage of it. I have been fortunate in these adventures to have been associated with men I trusted, usually my First Nations friends whose ancestors have travelled this country for so many centuries.

And so it happened that early in 1969 the government of the Northwest Territories began looking for projects that would typify life in the Territories in order to celebrate their centennial the following year. I sent a letter outlining my idea for a re-enactment of the Lost Patrol to show the close ties in the past between the NWT and the Yukon. I suggested that it should honour the Gwichin men who had worked as guides and special constables with the RNWMP patrol system and provided much of the skill that was required for the members of the force to survive long trips in adverse weather and inhospitable terrain. I knew that this was an opportunity that shouldnt be missed because, once the Dempster Highwaywhich was already under construction between Dawson City and Inuvikwas completed, the trail that the RNWMP had followed between Dawson and Fort McPherson in the early 1900s would no longer be isolated and the opportunity to experience it as it had been would be lost forever.

This, of course, has come to pass. Today people rarely use dog teams and even the Gwichin people hunt caribou from their trucks or snowmobiles. All the old guides who knew that route have died as have most of the men who accompanied me in 1970 on The Last Patrol.

Unfriendly Climate

The peaks and rivers presented a confusing choice of routes through the mountains.

As the small group of people stood around the four graves that had been dug with difficulty into the permafrost, five rifles were fired simultaneously into the frigid air in a military tribute to the four men they were burying. The graveyard in which they were laid to rest overlooks the Peel River, and to the west the Richardson Mountains stand out sharply in the clear air, but on this day no one was interested in the scenery. They were overcome by grief at the deaths of these men they had known so well. After a brief service, copper labels that had been locally manufactured were fastened to each of the coffins before they were lowered into the frozen ground and the volunteers were able to shovel soil over them. Then the mourners around the graves slowly broke up and made their way home to their cabins, all of them still feeling the shock of this tragedy that had occurred on their doorsteps.

In 1963more than fifty years after that funeral was held on March 28, 1911my wife and I came to live and work among the Gwichin First Nations people in Fort McPherson as nurse-midwife and outpost nurse. One beautiful summer day on a boat trip up the Peel River we learned the story of the four men who had died. When we landed on a grassy riverbank, we found a large wooden plaque describing how at this site in March 1911 a search party led by Royal Northwest Mounted Police Corporal W.J.D. Jack Dempster had found the bodies of Inspector Francis Joseph Fitzgerald and Special Constable Sam Carter, who had perished on an aborted winter patrol from Fort McPherson to Dawson. We were told of another plaque a few kilometres farther up the river that marked the spot where the bodies of the other two members of that patrol had been found.