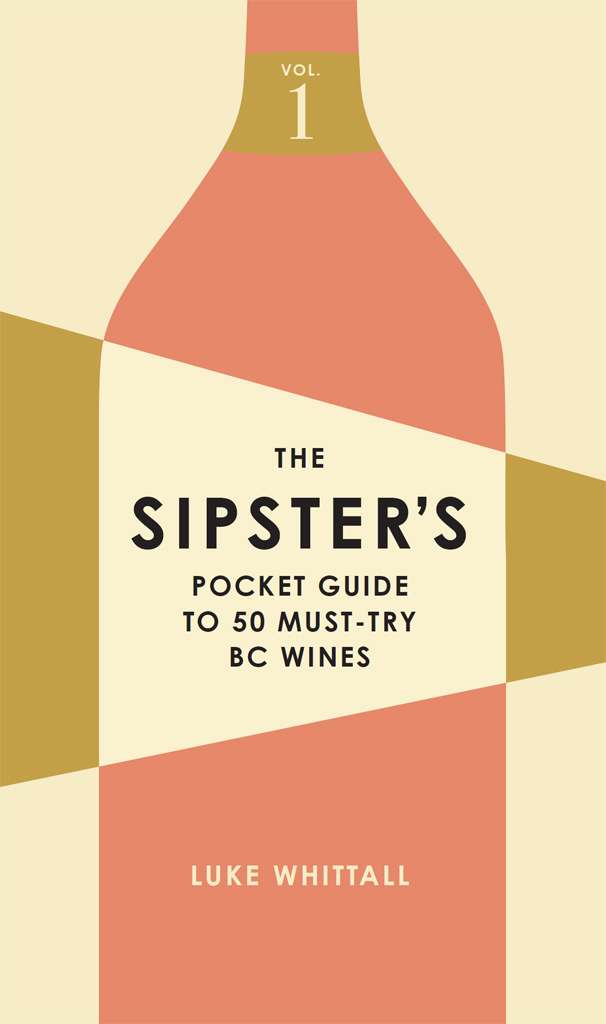

Copyright 2021 by Luke Whittall

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For more information, contact the publisher at:

TouchWood Editions

touchwoodeditions.com

The information in this book is true and complete to the best of the authors knowledge. All recommendations are made without guarantee on the part of the author or the publisher.

Edited by Meg Yamamoto

Cover and interior design by Sydney Barnes

Photographs appear courtesy of the wineries

CATALOGUING DATA AVAILABLE FROM LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA

ISBN 9781771513609 (paperback)

ISBN 9781771513616 (electronic)

TouchWood Editions acknowledges that the land on which we live and work is within the traditional territories of the Lkwungen (Esquimalt and Songhees), Malahat, Pacheedaht, Scianew, TSou-ke and WSNE (Pauquachin, Tsartlip, Tsawout, Tseycum) peoples.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and of the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

This book was produced using FSC-certified, acid-free papers, processed chlorine free, and printed with soya-based inks.

Printed in China

25 24 23 22 21 1 2 3 4 5

This book is dedicated to Miles and Vanessa, who constantly remind me what is important in life.

sipster

sipster | \ sip-st r \

r \

: one who observes, seeks, and sets taste trends of sipping beverages,

such as wine, spirits, tea, and coffee, outside of the mainstream.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

We all enjoy wines on different occasions and for different reasons. Unfortunately, many wine-shop tasting bars and winery tasting experiences do not feel like any situation where I could really enjoy wine. The idea of standing up at a crowded tasting bar with forty other people vying for the attention of the staff members behind the bar is not the best way to enjoy a wine, in my opinion. Until the recent pandemic made most of us realize that there were better ways to experience wine at a winery, I felt like I was the only one who was irritated by this. I enjoy my wine sitting at a table, in a comfy chair, on a picnic blanket, or at a reception. When I test drive a car, I want to take it on the road, not drive it around a parking lot with strangers in the back seat.

Wine-tasting notes and reviews dont seem to help, since they often misplace our real sense of value for wine. They build up wines using long lists of aromas, flavours, and miscellaneous production information. Some of this information is useful for people involved in the wine industry (salespeople, sommeliers, and enthusiasts), but most of it is not going to really help you find a new wine to enjoy.

As the wine importer Terry Theise has said, wine is a moving target. Even expert wine judges, who are certainly highly skilled tasters, can come to different conclusions about the same wine. Human chemistry, environmental factors, and preconceived perceptions about a wine (as simple as being able to see the colour of it before tasting it) will alter how much or how little we will enjoy a wine. As Bianca Bosker says in her recent book Cork Dork, no taste is pure.

There must be a better way to learn about great wines.

HOW WINES ARE TRADITIONALLY EVALUATED: TASTING NOTES

Communicating about wine is a serious issue, for those in the industry in particular but also for people who love to read (or write) about it. It has all become a bit silly over the past few decades because we have not fully developed a language to talk about it. Communication about any art form has this same problem. As the popular quote goes, writing about music is like dancing about architecture. (This has been attributed to the comedian Martin Mull and the composer Frank Zappa, among many others.) How does one distill an art form that needs to be experienced by a person into a form that can be accurately communicated to other people who have not experienced it and cannot possibly experience it at the same time?

With wine, the traditional form of communicating about it has been through tasting notes. These snippets of snappy language appear in newspaper wine reviews, wine magazines, blogs, and apps. They usually list a bunch of aromas and flavours that the writer of the tasting note perceived when they sampled the wine. The writer will likely taste the wine aggressively, a style of tasting that Terry Theise, in his book Reading between the Wines, says aims a beam of concentrated attention directly at the wine, using your palate to take a sort of snapshot. This is the kind of tasting that wine students use when studying wine. There is a technique to it that must be learned and practised regularly to achieve consistency. It is not an easy method, but most anyone (lacking any physical impairment such as anosmia) can learn to do it.

Tasting notes are a relatively new concept in the wine industry, though their ubiquity for todays wine lovers makes it seem as if theyd been around since the invention of wine. This would be true if wine had been invented in the early 1970s in California, but of course it was not. Credit for the vocabulary that provided the rocket fuel for tasting notes goes to Ann Noble at the University of California at Davis, who developed the Wine Aroma Wheel. The inner sectors of the brilliantly designed aroma wheel contain general aroma groups as they might appear to the person sensing them: fruity, herbaceous, floral, woody, earthy, or chemical, among others. These groups are then broken down over the next sectors, moving away from the centre of the wheel. Fruity breaks down into all of the different families of fruit flavours, such as citrus, berry, tree fruit, or tropical fruit. Those categories can break down even further. If its a berry flavour, what kind of berry? Currant? Blackberry? Strawberry?

The Wine Aroma Wheel provides a simple system that has allowed us to create a vocabulary for smells, which is something the English language has never really emphasized. Going back to Plato, our sense of smell was deemed unimportant and unbecoming of a civilized, rational person. There are not a lot of aromatic descriptors or expressions in the English language. For example, take the way in which we might describe cheese. The French language has expressions such as les pieds de Dieu, which is an elegant way to describe the stinky character of some types of cheeses. In French the feet of God, in English stinky. Which one sounds more enticing?

The aroma wheel was a brilliantly simple solution to a complex problem in a language that lacked the vocabulary. For students studying wine, wine enthusiasts, or anyone related to the wine industry in some way, it works. But for me, and perhaps most people, the list of flavours was perplexing at first, particularly for wines from lesser-known regions. (Wet wool? Diesel? I should want to drink that?) Why was it proffering aromas and flavours anyway? What good is that? Shouldnt they all just taste like wine? So a wine smells like candied strawberries, tastes like dried herbs, and has a long, dry finish. What can I do with that information? The obvious answer is that if you like eating or smelling those things listed under aromas and flavours, then you have a good chance of enjoying the wine. If a wine has notes of cranberries and you, as the wine drinker, do not like cranberries, then what are the odds that you will like the wine? Probably fairly low. What if the idea of tasting cranberries in a wine is completely weird for you? Average wine consumers dont have a lot of information to go on with tasting notes like this. No wonder people are confused about wine. As Bianca Bosker says in

r \

r \