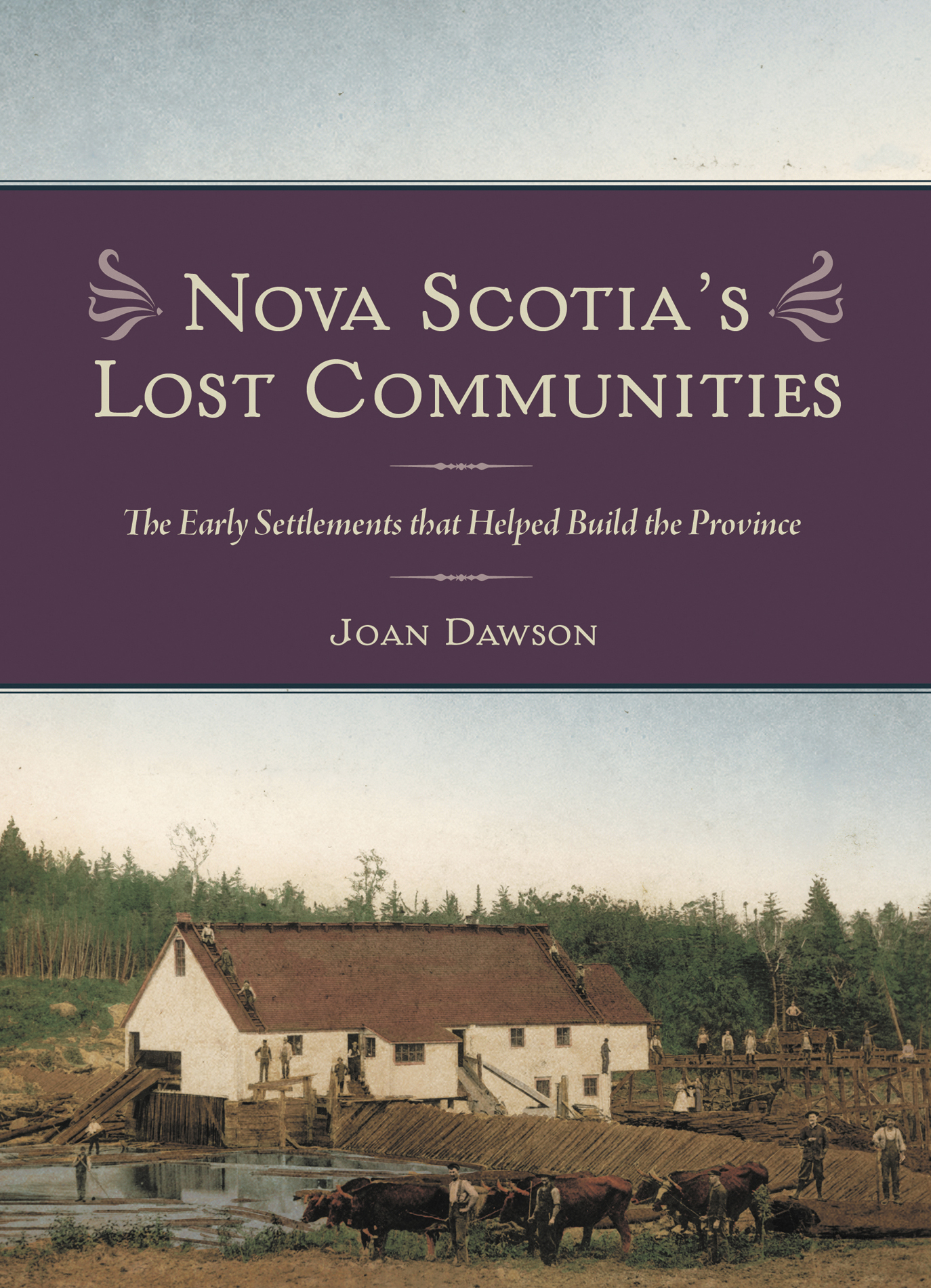

Travelling along Nova Scotias rural highways, we often see abandoned buildings and tumbledown barns, ruins of the failed ambitions of the folk who built them or symbols of the changing fortunes of their descendants who could no longer maintain them. But there are also places where whole communities were once found, whose traces are now mostly invisible. Some are indeed ghost towns, either reclaimed by the forest that was once cleared for their development, or ploughed over for farmland. Some have left clues above ground: an old foundation or the remaining pattern of a former street plan, while some are discernable only to archaeologists. Some were deliberately destroyed, and others simply abandoned in the face of a changing economy and lost to the ravages of time. And some have been supplanted by modern structures that bear no resemblance to the buildings that were once there.

As I was driving along the highway one day, one of my sons suggested that perhaps I should consider writing about these lost settlements. We started to think of some examples. Drumming on the steering wheel, I quickly used up the fingers of one hand and moved on to the next. With that hand also exhausted, we moved on to our toes, lost count, and I began to realize that perhaps this topic did indeed provide the makings of a book.

You, too, may be surprised to learn how many of Nova Scotias former communities have been obliterated by time or by human activity. But they were established by real people who made their living there. Why did they choose to settle in those locations in the first place? Why were their communities later abandoned? Exploring the history of these places has been a fascinating journey.

Introduction

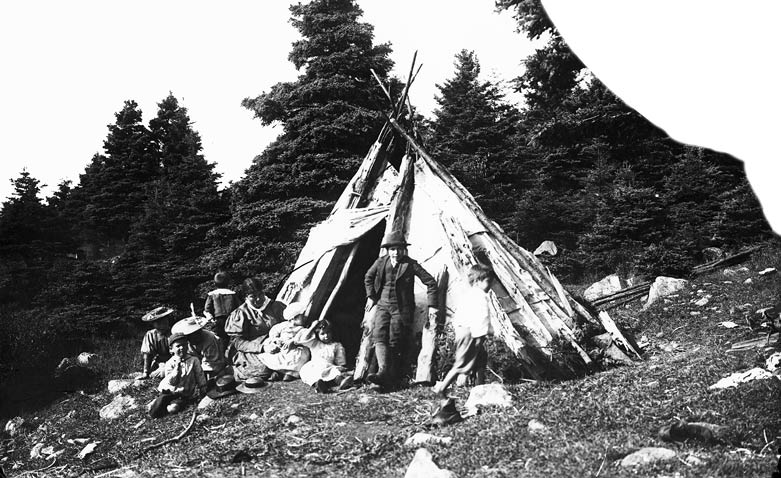

A Mikmaw family is shown in front of a wigwam in this photograph dated ca. 1895.

Nova Scotia Archives

An aerial view of what we now call Nova Scotia, before Europeans came to these shores, would show almost all of the region densely forested and with little evidence of human habitation. The Mikmaq who inhabited the area lived in the forest, along the rivers and shores, and were often on the move, erecting their wigwams at campsites along the way and again at their destination, and leaving virtually no discernable footprint behind.

This pristine aerial view gradually changed. From the sixteenth century, European fishermen built wooden structures on the shore where they processed their catch and stored their gear when they returned home at the end of the summer. Later, permanent fishing stations were created and, over the years, people cleared land and established settlements based on natural resources, agriculture, trade, and industry, in various parts of the province. Some of these settlements were short-lived and soon vanished completely, while others flourished for a while and then dwindled from bustling communities into sleepy villages. Some were deliberately destroyed. Still others that are known to have existed once are now lost to more recent development that has eradicated all trace of them. But they all have a place in our history and should not be forgotten.

The earliest inhabitants of what is now Nova Scotia were the Mikmaq, who have lived for many thousands of years on their land that they call Mikmaki, that extends from Nova Scotia into Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, and the Gasp. Until modern times, they moved seasonally between inland hunting grounds and coastal sites where groups of families came together each summer to fish and gather clams, and to socialize. Because they were nomadic in those early days, their communities were not like the permanent settlements that Europeans built later. Groups of wigwams were constructed every year in traditional encampments, to be taken down and their birchbark covers carried away when the time came to move on. These Mikmaw encampments left very little mark on the landscape, leaving nothing behind but lost or broken stone weapons and tools, middens where they discarded animal bones and clamshells, stone weirs where they caught fish, and other signs of their presence such as traces of their wigwams and cooking fires that are discernable only by experts. The location of their seasonal settlements is known by oral tradition among the Mikmaq themselves, by historical records, and by evidence that has been discovered in the course of archaeological excavation.

The Europeans who came here in the sixteenth century were fishermen, who crossed the Atlantic in the spring and returned home in the fall. Although they frequently returned to the same harbours every year, they did not initially create settlements. In the seventeenth century, the French began a period of serious colonization, establishing trading posts and fishing stations in Acadie. Briefly, the Scots also established a foothold in the territory that they named Nova Scotia. Permanent settlements as we know them, including an administrative centre, were founded by the French on the Annapolis River, around the Bay of Fundy and Minas Basin, and on the South Shore. Marshland was dyked and drained for farming, and gristmills and sawmills were constructed in suitable spots on rivers and brooks. These Acadian villages survived several changes of government, and remained when mainland Nova Scotia was finally ceded to Britain in 1713. The French retained Cape Breton and established new fortified settlements there. The town and fortress of Louisbourg grew up, and was destroyed and left in ruins within forty years. The Acadian villages on the mainland were also destroyed or abandoned at the time of the