Copyright

Copyright 2013, Ruth Holmes Whitehead

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, permission from Access Copyright, 1 Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario M 5 E 1 E 5.

Nimbus Publishing Limited

3731 Mackintosh St, Halifax, NS B 3 K 5 A 5

(902) 455 4286

nimbus.ca

Printed and bound in Canada

NB1028

Author photo: Sandra Kipis, 2011

Cover and interior design: John van der Woude Designs

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Whitehead, Ruth Holmes

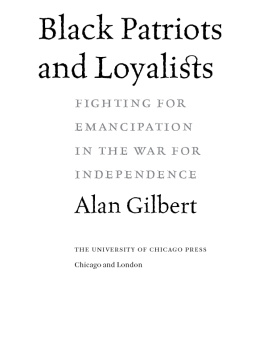

The Black Loyalists : southern settlers of the first free black

communities in Nova Scotia / Ruth Holmes Whitehead.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued also in print formats.

eISBN 978-1-77108-017-0

1. Black loyalistsNova ScotiaHistory. 2. Black loyalistsNova ScotiaBiography. 3. Nova ScotiaHistory1775-1783. 4. Nova Scotia--History--1784-1867. 5. United StatesHistoryRevolution, 1775-1783. I. Title.

FC2321.4.W55 2013 971.600496 C2012-907368-7

Nimbus Publishing acknowledges the financial support for its publishing activities from the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund ( CBF ) and the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of Nova Scotia through the Department of Communities, Culture and Heritage.

Introduction

I ts the third of May, 1783. In Barrington, Nova Scotia, a seven-year-old boy named These men and women would found the first free black communities in the province.

During the following months, and over the next two years, more than four thousand black men, women, and children would come to Nova Scotia as a direct result of the American Revolution (17751783). They came as freeborn persons, as former slaves who had seized freedom from the chaos of war, or as indentured servants. Some came still enchained to their enslavers. They came fleeing the British surrender of thirteen American colonies: the Massachusetts Commonwealth (which then included Maine), New Hampshire, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. During the course of the war, as these colonies fell one by one to the victorious Americans, mass evacuations of British forces and supporters to their remaining centres of power began to take place.

As early as 1775, slaves were being promised freedom if they deserted rebellious colonists to come behind the British lines. Many of them took advantage of this offer, following the British Army or sailing with the Royal Navy, as the lines of battle and power surged up and down the Atlantic Coast. Historians now refer to these people as the Black Loyalists a term that seems to have been extended to cover all the blacks who emigrated to Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Quebec, whatever their circumstances, between the years 1775 and 1785.

The colonies of Newfoundland, Nova Scotia (which at that time included what is now New Brunswick), le Saint-Jean (later Prince Edward Island), and Quebec had remained loyal to King George III of England throughout the revolution. In the south, East Florida never left British control (West Florida was retaken by the Spanish toward the end of the war). Midway between the two lay the city of New York. By August 1776, the British were entrenched in New York, holding it until the end of the war. Thus, by 1783, the bulk of Black Loyalists, enslaved originally all along the east coast from Georgia on up through Maine, were concentrated in New York, the port from which many would later sail to Nova Scotia.

They would not be the first Black Loyalists to come to Nova Scotia, however.

For all practical purposes, the American Revolution ended in October 1781, with the surrender of General Cornwallis to General Washington at Yorktown, Virginia. Sporadic fighting continued in other places for several months. As the British were evacuating Savannah and Charlestown from July through the end of December 1782, more persons poured into New York. By April 1783, the first transports had begun taking thousands of British and Hessian troops home to Great Britain and Germany. With them went many who had been loyal to Britain, black and white, with their families and the little they had been able to salvage from the wreckage of war. Refugees also made directly for Nova Scotia, sailed for the West Indies, or took ship to Quebec. Others went to St. Augustine, East Florida, where they were promised peace, provisions, and land.

Florida was not to remain a refuge for long, however. The English colony of West Florida was retaken by the Spanish prior to the signing of the peace treaty in 1783, and East Florida by that same treaty was ceded back to Spain, with its refugees and old settlers given until 1785 to complete evacuating the territory. Many of these opted for the same promises of provisions and land in Nova Scotia, far to the north.

A number of excellent books have told the story of the part played by black men and women in the American Revolution. Others have written about the arrival of the Black Loyalists in Nova Scotia, and the departure of many of them, in 1791, for a new life in Sierra Leone all good general surveys. This book, however, is much more specific, taking a look at those founding members of the Black Loyalist communities in Nova Scotia whose stories began in the southern provinces of South Carolina and Georgia (which was carved out of South Carolina in 1732). I chose the South Carolina Black Loyalists to focus upon particularly because that province, before the American Revolution, had the largest black population of any in North America; many contemporary Nova Scotians who are descended from Black Loyalists have ancestors who were enslaved there. South Carolina is also where I was born, and a number of my own ancestors there were slave owners who lost people to Nova Scotia. As a former registrar at the Charleston Museum, I knew the research infrastructure. It seemed a good place to start looking at individual Black Loyalists, following them through the war that led to their arrival in Nova Scotia. This book is an attempt to recover their history and that of their contemporaries for their descendants, many of whom live in Nova Scotia today.

How their names have survived is an interesting story in itself. All people are a treasure house of information, of personal memories. If we are fortunate, ancestors pass some of this down to us. Nowhere on earth, however, has the generational transmission of history been cut more devastatingly than in the forcible migrations whereby an estimated ten million persons of African birth were brought as slaves to the New World. Torn away from their heritage, their extended families, their languages and culture, these men and women have left to their descendants often little more than a handful of memories.