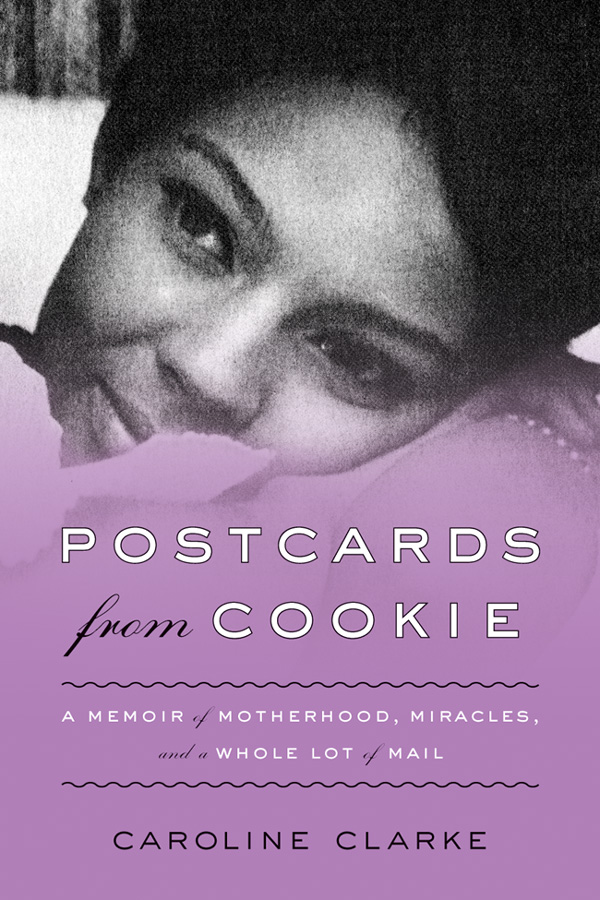

For Veronica and Carter

Everything comes to us that belongs to us if we create the capacity to receive it.

T AGORE

Mine is not a war story of endless effort. It is a story of ease and unearned blessings.

O RIAH M OUNTAIN D REAMER

Contents

I grew up listening to my parents and their siblings recount old tales of their own growing-up years. It was always fascinating to hear multiple versions of the same incident told by people who were in exactly the same place at precisely the same time. The debates over whose version was the real one were lively and never ending. And so it goes with the truth; we each have one, each is distinct, and each is realat least to us.

This is a true story, but it is only my truth. With very few exceptions names, dates, and locations are authentic, as are reproductions of correspondence and images, lyrics, and poems. The rest is drawn from memorymine and a few generous others.

Memory is a funny thing. Its a powerful and fallible source that, in the end, makes us who we are.

T he February sky is bright, but a rush of wind helps push open the door as I step into the lobby of Spence-Chapin Family Services, the adoption agency to which I essentially owe my life.

Its been thirty-seven years since my parents walked out of this very same building, on another cold winters day, with me swaddled in a pile of pink blankets, newly their daughter at one month old.

I dont realize it now, as I step from the blustery midday light into Spence-Chapins timeworn lobby, but my whole world is about to shift again.

Ive returned to talk to Amy Burke, who happened to pick up the phone when I called. In response to my request for medical information, shes gone searching through my dusty adoption records and is prepared to share with me whatever the law allows, which I know isnt much.

I was born in an era when adoptions were shameful, secretive, and sealed. Whether you were giving up your baby or getting oneboth daunting endeavorsyou were urged to forget the whole process the moment it ended and just go live your life. Thats exactly what we all didmy parents, me, and, I presume, my birth parents too. But here I am, back, perched in a beat-up pleather chair, waiting for Amy-the-social-worker to tell me what shes found.

Im not an unhappy adult adoptee longing for clues to my past, dipping my toes into the searchable waters in hopes that a magical current will carry me home. I already have a home and parents who have always loved me well and with abandon.

You were given up at birth is a tough notion to swallow when youre seven years old.

Youre the child we always wished for made it go down a lot easier.

Knowing I was adoptedthat I could have had some other life with some other family in some other placeonly made me love and appreciate my parents more. They are not genetically mine, they were made mine by God, fate, the universetake your pick. Ive always known I am one lucky girl.

Now happily married with two children of my own, a career in journalism that I love, and too many blessings to count, Im nonetheless anxious about a small list of health concerns including joint pain in my knees and hips that has been recurring for years. Tests for lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and assorted other genetically linked ailments repeatedly come up negative. The symptoms always subside but inevitably return, cuing deep self-doubt about the fortitude of my genetic makeup.

My misgivings peak every time a new specialist quizzes me about my parents and grandparents health. So does my frustration. Virtually every question they ask yields the same tired response: Im adopted. I dont know.

Worried that I might be passing health problems down to my seven-year-old daughter, Veronica, and my son Carter, four, I called Spence-Chapin hoping for a peek into my hidden medical past. Given that I know absolutely nothing about it, even the smallest disclosure would be compelling.

It isnt my first contact with the agency. Five years earlier, I had made a donation in honor of my parents on their fortieth wedding anniversary. It was 1997 and I was already full-grown and a mother myself, but my folks were as devoted to me as ever, and now to my husband and children too. Id never be able to repay them for all theyd given me; the gift to the agency that gave us to each other was the least I could do.

No sooner did Spence-Chapin receive that check than they were ringing me up, the start of a courting ritual designed to draw me in as a regular donor and participant in their postadoption programs. Having simply been raised as my parents child, not their adopted child, I knew nothing about such things, but I would soon learn that adoption and its potential aftermath had evolved a great deal.

Unlike three dozen years ago, when my parents left the agency with little more than a wave and a wish of good luck, Spence-Chapin now hosted all sorts of support groups, counseling programs, and regular gatherings to celebrate adoption. It also helped facilitate searches. For adoptees like me, whose records were sealed with tomblike finality, there are national registries where matches can be made if both children and birth parents submit their information. There is also very limited nonidentifying information every adoptee can receive simply by requesting it. This generally includes medical information and skeletal facts, such as physical descriptions of birth parents, or their occupation at the time the child was born.

Initially none of it interested me and I might never have set foot back in Spence-Chapins converted Upper East Side townhouse if not for my health concerns. My November call to the agency to ask what I had to do to obtain a medical history had been rote. Per simple instructions, I sent in a notarized request, and in mid-January Amy Burke called back with news.

Apparently my birth mother had lived under the agencys care for several months and, as a result, my records were more extensive than most. While information that could identify her or my birth father remained sealed, the agency was at liberty to share nonidentifying medical and personal details at its discretionin other words, at Amys discretion. But heres the catch: I have to go get them in person.

Amy cautioned me to make the appointment for a time when Id be unencumbered afterward. I work. I have two kids. Im never unencumbered.

People are sometimes distracted after these meetings, she explained, her voice brimming with concern.

Even without identifying information, whatever is offered could be a lot to take in, she warned.

Unfazed, I ignored her advice. What could she possibly tell me that would throw my whole day? But now, sitting in the lobby of this place where my life essentially began, I feel uneasy. As I glance through a photo album of wide-eyed children with their gleeful new parents, unbidden tears suddenly blur the images, causing me to hastily put the book aside, wipe my eyes, and check my watch. Its time to get on with this and get back to work.

Before long Im ushered into a small room with high ceilings, bare windows, linoleum floors, and two mismatched chairs, left over from another era, facing each other. Ive never been in an interrogation room, but something about this place makes me think of one. Maybe its the sparseness or utter chalk whiteness of it. Either way, I dont like it.

Amy, on the other hand, is a pleasant surprise. After two brief conversations on the phone, I wasnt sure what to expect. Prim and professional, her face melts into a warm smile when she reaches out to shake my hand. The fact that, like me, shes African American and maybe just a few years my senior, helps to put me at ease. This process feels so alien; she is at least somewhat familiar.