For Professor Sheehan

The Harvard Common Press 535 Albany Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02118 www.harvardcommonpress.com

Copyright 2012 by Howard Stelzer and Ashley Stelzer

Photographs 2012 by Jerry Errico

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed in China

Printed on acid-free paper

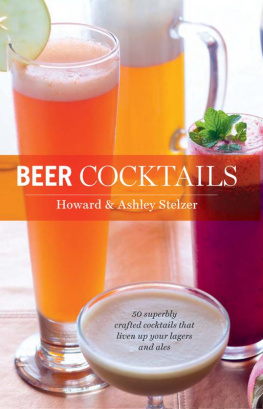

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stelzer, Howard. Beer Cocktails : 50 superbly crafted cocktails that liven up your lagers and ales / Howard Stelzer, Ashley Stelzer. p. cm.(50 recipes series) Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-55832-731-3 (hardback) 1. Cocktails. 2. Beer. I. Stelzer, Ashley. II. Title.

TX951.S798 2012

641.23dc23

2011039026

Special bulk-order discounts are available on this and other Harvard Common Press books. Companies and organizations may purchase books for premiums or resale, or may arrange a custom edition, by contacting the Marketing Director at the address above.

Book design by Elizabeth Van Itallie

Photography by Jerry Errico

Drink styling by Chris Lanier

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all of our friends and family who offered ideas, tasted recipes, and generally encouraged our inappropriate behavior during the writing of this book. Particular thanks to our good pal Jay Sullivan, head brewer at Cambridge Brewing Company, for offering thoughts and expert advice along the way. Thanks also to Jonathan Coleclough and Brian Preston-Campbell for sharing their own beer cocktail exploration notes. Cheers! Merci to Eben Freeman, director of bar operations and innovation for AltaMarea Group in New York City, upon whose recipe we based the Bloodied Belgian. Dank u wel to Terry Raley at Holland House in Nashville, and to Paul Clarke. We extend expressions of gratitude toward our fellow liquid travelers AJ. Rathbun, Fred Thompson, and Paul Abercrombie for setting a good example. Thanks to Bruce Shaw, head honcho at The Harvard Common Press, for his enthusiastic support and encouragement, and of course to our editor, Valerie Cimino. Further thanks to every one at HCP for making it all possible. These friends and enablers also deserve a drink or two: Terryl Montgomery (for all the pilsner glasses!), Elizabeth Brash, Teryn Williams, Carrie Holmes Siegel, Christine Merlo, Darren Hutson, Preston Reed, Jerry Spindel, Vicki Milstein, Sandy and LeeAnn Brash, Eagranie Yuh, Peter Perez, Pete Swanson, Benny Nelson, Jason Lescalleet, Vic Rawlings, Elizabeth Witte, Greg Kelley, and Christina Divoll. Lchaim, yall!

Introduction

Its quite possible that beer is the worlds perfect beverage.

In his book Radical Brewing (Brewers Publications, 2004), Randy Mosher claims that waiting for grain to ferment is what tempted prehistoric nomads in the Fertile Crescent to settle down in one place. That tale, if you believe it, places beer at the center of the start of modern civilization.

Whatever ones take on Moshers wistful interpretation of history (were pretty sure there were some additional factors), it is true that beer has been with us for thousands of years. People enjoyed the product of fermented grain in water before the invention of bread. From Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt (where it was used as medicine), beer spread outward across the world. Brewers could be found in medieval Europe and China; explorers and travelers brought beer across the ocean to the Americas, to Africa, Australia, and New Zealand, and to nearly every country on Earth. Over time, the humble beverage evolved into an astonishing variety of styles shaped by diverse cultures and native ingredients.

Here in America, beer went through major changes in a relatively short amount of time. Most beer before the 1800s was ale, which means that because of the yeast brewers used, it fermented at a warm temperature for just a few weeks. The Industrial Revolution at the end of the nineteenth century brought with it the development of paler malt, pilsner lager, commercial refrigeration, and machines that could perform parts of the brewing process automatically on a large scale. With those advancements came beers that could stay fresh for longer and ship far away with less risk of spoiling. Technology effectively created competition for small local brewers.

In the early twentieth century, the Eighteenth Amendment temporarily halted large-scale beer production, but it also made home brewing illegal. When it was repealed in 1933, industrial brewing returned to the United States, but brewing beer at home remained a crime. That didnt change until 1978. In the intervening years, Americans access to beer was quite limited. National brands such as Anheuser-Busch grew during that time, marketing and selling homogeneous products designed to appeal to the most people possible across the widest expanse of demographics and geography. These very pale beers, watered down further with adjuncts (additions) like rice, effectively replaced Americas regional and local styles as the popular favorites. For most American beer drinkers during that time, anything other than these lagers was suspiciously unfamiliar.

Thankfully, the legalization of home brewing also sparked a wave of independent brewpubs and microbrewers. The steadily growing availability of different kinds of beer increased the demand for imports as Americans rediscovered beer. Home brewers began to experiment freely with the new diversity of styles now accessible to them. Interest in noncorporate beer began to surge. The Anchor Steam Brewing Company made a big, early impact by reviving steam beer, a uniquely American style once popular in San Francisco, inspiring other home brewers to go pro as well.

We now live in an age in which curious thrill-seeking drinkers can seek out and sample beer from just about anywhere in the world. One used to have to travel to the pubs in England to sample the local brew or visit a Belgian abbey to try the legendary beer made by Trappist monks. Today, geography is not an obstacle. Creative brewers in Tokyo are making American-style India pale ales; a Colorado brewery specializes in Belgian styles; Russian brewers are making German-style maibock; brewers in Seattle are tweaking English styles using hops from the Pacific Northwest; and the list goes on. It isnt uncommon to find at least a small sampling of beers from Germany, the UK, Canada, and a few American regions in your average corner store or supermarket. The changes are coming with remarkable speed. As recently as ten years ago, the taps of most bars, even in a beer-conscious city like Boston (where we live), offered only the big national brands. Nowadays, youd be hard pressed to find a bar that doesnt offer at least a couple of local brewers products. Beer pairing is becoming as common as wine pairing at dinner. This all points in one direction: More and more people are demanding better beer.

Which brings us to ... beer cocktails.

1. BEER BASICS

So, now that weve established that beer is a delicious, historically and culturally significant beverage, why would you want to add anything to it? Dont we owe those hard-working brewers the respect of enjoying their creations in as pure a form as possible? To that rhetorical question, well-intentioned and naively sentimental though it may be, we say: nonsense. Beer is deserving of respect and appreciation, but no liquid is sacred in the world of cocktails. Cocktails are as creative a culinary expression as any other, and the best drinks demand excellent ingredients. In fact, anyone who mixes a drink is already drawing upon high-quality creations to build something new. Just as you might mix a fine bourbon into a Manhattan or a small-batch gin into an Aviation, so can and should you mix quality beers into great cocktails. With all the combinations of flavors and textures in the world, there is no reason to limit our libations and not play with beer as an ingredient. Camper English, writing about beer cocktails at Epicurious.com, put it quite well: Many beer enthusiasts, like oenophiles and Scotch lovers, believe in the purity of their drink and dont welcome dilutions. Let them live in their gated communities.

Next page