Digitizing Audiovisual and Nonprint Materials

Copyright 2015 by Scott Piepenburg

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Piepenburg, Scott.

Digitizing audiovisual and nonprint materials : the innovative librarians guide / Scott Piepenburg.

pages cm. (Innovative librarians guide)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4408-3780-7 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-4408-3781-4 (ebook)1.Library materialsDigitization.2.Audio-visual materials Digitization.3.Nonbook materialsDigitization.I.Title.

Z701.3.D54P54 2015

025.8'4dc232015017442

ISBN: 978-1-4408-3780-7

EISBN: 978-1-4408-3781-4

191817161512345

This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook.

Visit www.abc-clio.com for details.

Libraries Unlimited

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911

Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

Figures 5.18 through 5.44 are courtesy of www.audacity.com, Copyright 2015 members of the Audacity development team. Except where otherwise noted, all text and images on this site are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, version 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). Audacity is a trademark of Dominic Mazzoni.

Contents

Walking through any library convention or exhibition, its not hard to find firms that will either digitize books, documents, photographs, and microform from your library or sell you the equipment to do it yourself. Perhaps your library or institution is part of a consortium that has a digital archives program where, for a nominal fee, you can have items scanned, stored, metadata created, and hosted, all in a single stop. This makes sense, since this consortial arrangement allows a group of users to spread the fixed costs of hardware, software, and dedicated staff over a larger area and allows them to develop specific expertise in their areas.

Many libraries, however, have more than books and photographs that are valuable. Perhaps there is a cassette recording of a local band concert or speech, or maybe some video footage either made by the library, another entity on campus, or the local television station that was donated to the library of an historic event. Some research libraries have footage of experiments that were taped for educational and professional purposes, or perhaps the library, archive, or university has some locally produced talks or public programming that is historically and educationally useful, but is too cumbersome to use, like in. U-matic tapes, or perhaps some first-generation Betamax (or Beta) tapes; maybe you have a collection of speeches on laserdisc from a company long since gone out of business or that are not available on YouTube or other similar resources. If you search for a vendor to convert these, you will quickly find that it is a small market with few vendors.

At a recent American Library Association (ALA) conference exhibit hall, there were only two vendors that offered audio and video digitization services. On the surface, this is a bit perplexing. Right now, whole generations of film and video, along with cassette, 8-track, U-matic, laserdiscs, and other plastic, magnetic, and optically based storage formats are quickly nearing the end of their life spans. In the ideal world, a collection of VHS videotapes that were used only infrequently should have been refreshed at least once a year by loading it into a player or fast-winder, running it all the way to the end, and then re-winding it; this process helps to re-seat the tape pack as well as help reduce any print through from too-tightly wound tape. As a side benefit, it helps the tape to breathe so that the adhesives binding the layers of tape together are regularly loosened and then rewound, thereby preserving their lives. The same applies to all forms of tape, including U-matic, Beta, cassette, and 8-track. 8-track tapes, if you have any, are particularly susceptible to wear because of the way they pulled tape from the center of the spool and re-loaded it on the outside. 8-tracks are a delicate balance of tension and lubricant that is easily upset by too much heat, cold, moisture, or lack of use. Its ironic that they found their biggest use in an environment known for extreme temperatures; that of the inside of an automobile.

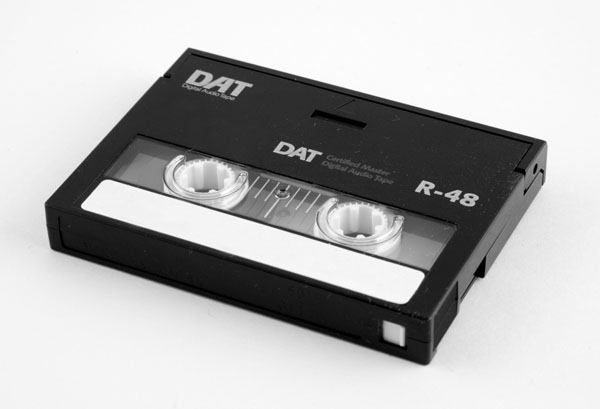

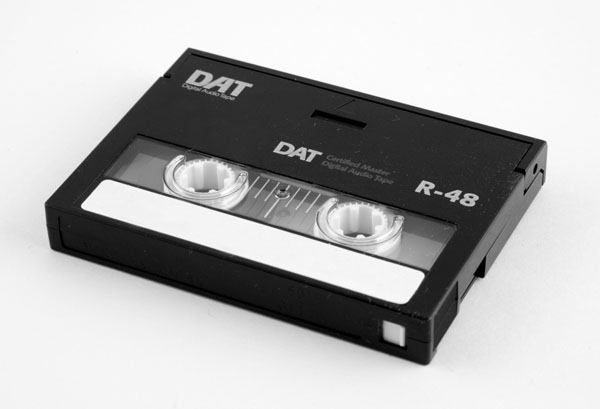

While rare, you may have some digital audio tapes and (DAT) and digital compact cassettes (DCC.) While both are digital, they also depend on a magnetic-based recording medium, leaving them susceptible to loss and damage over time, even with error correction. The danger is particularly severe with DCCs as they are a lossy format, with little extra space for error correction and redundancy. Released around the same time was the MiniDisc, a format that, like DCC, is lossy but is optically based; they had the benefit of being inside a sleeve, but again, they are not immune to age and there have been reports of discs failing over time.

Figure I.01A digital audio tape (DAT). (www.dreamstime.com)

Figure I.02A digital compact cassette (DCC).

Last, but not least, let us turn our attention to two disc-based formats from the 70s: the LaserDisc (developed by Pioneer and Philips, among others) and SelectaVision discs developed by RCA. While outwardly similar, they used different recording techniques; the LaserDisc was optically based, while SelectaVision used a needle in a groove format. Intended to be the next step in home entertainment, their high cost and inability for home recording led to their demise, although LaserDiscs did find a strong following in libraries and schools due to their large data storage capacity and ability to jump from frame to frame and freeze on a particular frame (depending on the recording method used.) These discs were popular for storing the art collections of museums, speeches, and for home use, feature-length films; their quality was far superior to what videotapes could offer even under the best of circumstances, but at a price, they were large, expensive, and one needed a good television or projector along with a fairly robust home theater system to appreciate them; because of this, they didnt catch on with the masses, although they were quite popular with the audio file set; looking at a release of Disneys Aladdin on VHS and its counterpart on LaserDisc, one sees there is no comparison; Disney pushed the envelope on LaserDiscs it released to highlight the quality of its work.

Figure I.03A SelectaVision disc in its carrier.

Of course, one cannot forget standard cassette tapes, reel-to-reel tapes (often locally made), record albums and singles, and many book on tape and book on record that were popular in the 60s but exist no more, not even online. Perhaps the library was an early adopter and had things like elcassettes, or maybe some old 78s in the collection, some of which might have been used for field recordings of oral history in the days before magnetic tape. Maybe you have some old cereal box recordings, or recordings used to advertise products or services (who knows what libraries keep; thats what archives are often for.) Many of these items are sitting somewhere, often unknown because they were passed over in the retrospective conversion projects as being too costly to do right now and well get to them later when we get the major work done. They then enter the old Catch-22 land where nobody uses them because they dont know they exist, and they arent cataloged because nobody uses them. Sometimes there is an old player that is sitting around that still works, or perhaps not. Maybe they are just sitting there, and to be honest, maybe they need to be weeded from the collection if there is no use for them or if they dont fit into the collection.