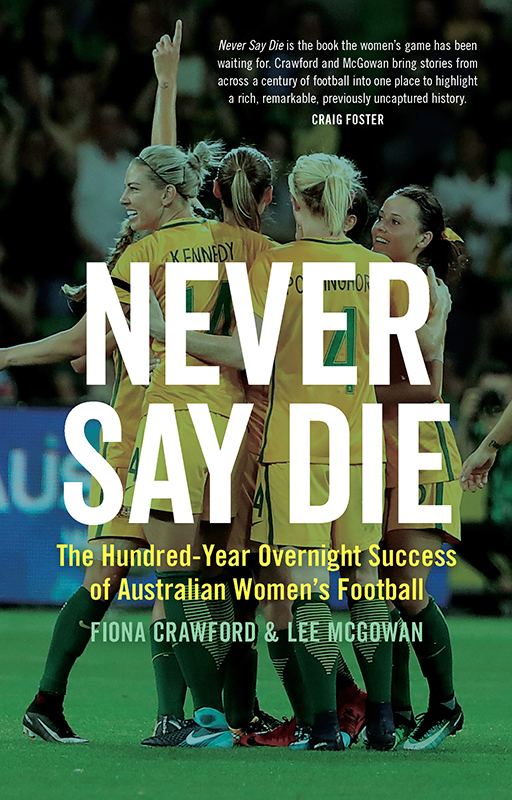

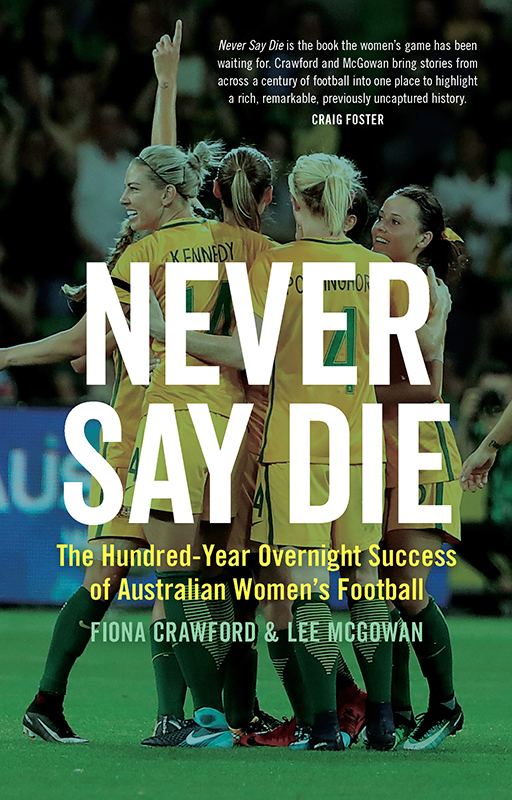

NEVER SAY DIE

FIONA CRAWFORD is a writer, editor, and researcher whose work spans social and environmental issues, the arts, and football. Fiona has written about football for many publications, including FourFourTwo, and has managed and produced content for Football Federation Australias womens football (Matildas, W-League, Girls FC) social media. Her PhD investigated how the Homeless World Cup uses football to tackle, and change perceptions around, homelessness.

LEE MCGOWAN is a researcher and writer at the Queensland University of Technology. He is collaborating with Football Queensland on a digital history of womens football and working on a range of other publications. His football research has featured on SBS World News, Australian Story, ABC radio, and in the Courier-Mail. He recently completed the academic text Football in Fiction: A History.

NEVER SAY DIE

The Hundred-Year Overnight Success of Australian Womens Football

FIONA CRAWFORD & LEE MCGOWAN

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

Fiona Crawford and Lee McGowan 2019

First published 2019

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

ISBN9781742236667 (paperback)

9781742244716 (ebook)

9781742249216 (ePDF)

Design Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design Lisa White

Cover image Sam Kerr of the Matildas celebrates after scoring a goal during the womens international match between the Australian Matildas and China PR at AAMI Park on 22 November 2017 in Melbourne, Australia. Photo by Robert Cianflone/Getty Images.

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The authors welcome information in this regard.

This project is supported by the Australian Academy of the Humanities.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

In monsoonal conditions on the evening of 30 May 2010, 16-year-old winger Sam Kerr put her teammates, the Matildas, one goal ahead. She did so with an uncomplicated confidence and the deftness shes now known for, which was even more impressive given the waterlogged playing surface. It was the 19th minute of the Asian Football Confederation (AFC) Womens Asian Cup final. The Matildas maintained their lead into the second half, but with 17 minutes remaining, buckling under the tide of pressure from their DPR (North) Korean opponents ranked sixth in the world the exhausted and soaked-through Australian national team conceded what seemed like an inevitable equaliser. The North Korean goal would see both teams play a nail-biting 30 minutes of extra time.

When the final whistle blew, barely audible in the thunderous rain, the score was still even. There would have to be a penalty shootout to determine the victors. Few footballers or football fans relish a penalty shootout. The Australians surrender of a 20 lead to lose to China on penalties at the 2006 tournament, and the desire to redeem that result, may have been on the Australian players minds as each team nominated five penalty takers.

Each player took their penalty: a single shot from a designated spot in front of the goal with only the goalkeeper to beat. Behind the keeper, barely visible through the pouring rain, thousands of fans waited, willing a miskick or a fingertip obstruction from the keepers glove. No player wanted to be the first to miss their penalty kick.

The Australians had scrapped and battled with everything they had to get to the final of the most prestigious international womens football tournament in Asia. Their ranking (12th in the world) suggested a higher-ranked team such as China or South Korea should have had the spot. Emerging victorious from the semi-final clash with one of the worlds powerhouses, the fifth-ranked Japan, was a huge ask. But the Matildas managed it.

The players left standing on the pitch for the final were drawn from a squad decimated through injury. Key striker Lisa De Vanna, for example, was missing after having broken her ankle in the third group game. It was a game for which coach Tom Sermanni had planned to rest her, but she pleaded with him to play. She sustained the injury within five minutes of being on the pitch. Distraught that she couldnt play the final, De Vanna refused to take painkillers so she could remain lucid and feel every emotion of the game. Tightly gripping teammate Thea Slatyers hand, she cut an anguished figure on the sidelines.

It all came down to one kick. The Australians were at a psychological disadvantage, having lost the lead and the momentum, and both sides had just completed 120 exhausting minutes of ferocious contest in conditions that would see most games called off. One of the North Koreans had scuffed their penalty wide of the post. Taking the final penalty, 18-year-old Kyah Simon showed no sign of nerves as she placed the ball. She sized up the strike, took a couple of settling breaths, and picked her spot. In the few small steps and the shot that followed, Simon embodied the national teams never-say-die motto and captured everything that led to their success. That final penalty in Chengdu, China, marked the realisation of decades of female footballers dedication, resilience, and sweat, and proved an important milestone for the national team.

With that kick, which gave the team a thrilling win over North Korea, the Matildas, long overshadowed by mens football and largely ignored by both the governing body for the sport and commercial broadcasters, became Australias most successful football team. This should have been the result that finally brought Australian womens football into the spotlight. But apart from some brief mentions of the Matildas win, the following days sports pages were, as per usual, mostly filled with stories about male rugby league players and male Australian rules football (AFL) teams. Readers were offered insight from Socceroos goalkeeper Mark Schwarzer on the new football Adidas had designed especially for the 2010 [Mens] World Cup. The Matildas, who had become a symbol and benchmark for the next generations they continue to inspire, returned with little fanfare to their W-League clubs and their part-time jobs.

The story of Australian womens football is one of both substantive international achievement and domestic challenges. It starts with grassroots games organised 100 years ago and features a sadly familiar struggle against gender bias. While it would be nice to think that poor attitudes toward female footballers are just a historical curiosity, most of the sentiment that prevailed then remains pervasive today. There are countless illustrative examples from 50 years ago or yesterday. Stories of men training on the good pitches while the women were relegated to the poorest, least-lit pitches (or even a local high schools oval pockmarked by students shot put practice). Of women having to change into their playing kit in their cars, or arrive fully dressed because there were no changeroom facilities. Of women lost to the sport because the physical, mental, and financial exhaustion of trying to juggle training, work, study, and poorly supported injury rehabilitation became too wearying. There are stories too of top male football administrators the ones pulling Australian footballs levers of power telling female football administrators that no one wants to watch womens football. And of men being at first baffled and then incensed when a grassroots clubs female footballers asked for the changerooms to stock a single sanitary bin.

Next page