The future is feminine

F EDERATION OF I NTERNATIONAL F OOTBALL (FIFA), J UNE 1995

S epp Blatter was pleased. The future is feminine had an impressive and authoritative ring to it. It was just the sort of soundbite certain to be picked up by the worlds media, and would therefore ensure much-needed exposure for FIFAs Womens World Cup, then in its infancy. Blatter didnt, of course, believe it. But the career-minded sports administrator hadnt got to the position of being the favourite to win FIFAs forthcoming presidential election by allowing such minor matters as belief to over-trouble him. No, The future is feminine was good and Sepp Blatter liked it.

He liked it so much that once elected he would go on to repeat it over the ensuing 15 years. The difference was that on these occasions always timed to coincide with a major FIFA womens competition he actually believed in the soundbite. And, in truth, he had good reason. Global mens football, FIFAs cash cow and the very reason for its existence, had to a large extent reached its maximum business potential. Television rights to the World Cup would, of course, continue to rise in price and fill FIFAs coffers but it had pretty much reached saturation level on every continent. If a new income stream was to be found, it wouldnt be in the mens game. Womens soccer well, now, that could be a very different story, and a very profitable one, to boot. A new series of international football competitions meant new sponsorship and, most importantly, a whole raft of new television deals.

This isnt a book about FIFA. Fascinating though it is, other journalists and writers have devoted acres of newsprint and millions of words to the allegedly Machiavellian politics of the sports supreme governing body. Nor is it a book about football at least not in the sense of a traditional football book. Indeed, of all authors you could name I would probably be one of the least qualified to write about the technical skills and aspects of football, let alone the who-won-what-when statistics which are the staple ingredients of any conventional soccer book.

I am happy to admit that I havent knowingly watched an entire football match since 1990 and would be hard put to name any of the leading players in national or international sides. In sport, my passion is, and always will be, rugby union as a player (absurdly briefly), as a life-long spectator and for 10 joyous years as a coach. And so whilst there will be (for reasons that will become clear) at least passing references to, for example, the arcane mysteries of the offside rule, the development of the 4-4-2 formation, and the occasionally eye-watering finances involved in the game, this book is not written in the thrall of a life-long passion for all things football.

Instead its a book about people: extraordinary figures from a dimly-remembered past, figures who were both of their time and who shaped it. But although its a book about the past, and will dig deep into the loam of British social history, its also about why the present is as it is.

As you might expect from the title, many of the characters in this story are women. Their struggle to play a sport they loved was fought out against a backdrop of huge social change in Britain. When womens football began and it began surprisingly early in the overall history of the game men alone had the vote and the only sporting activity considered suitable for girls was croquet, with the occasional dash of very demure cricket. When its golden era ended, surprisingly late, Britain had universal franchise and Barbara Cartland was driving racing cars round the Brooklands circuit.

The story of womens football reflects the story of the decades which transformed Britain from late Victorian claustrophobia into the open spaces of the 20th century. Other books have been published which examine small corners of this story: a list is included at the end and I heartily recommend each one. But each is somewhat hamstrung by the limits its author has placed on it, whether it be a privately-published account of the successes and failures of women footballers in the north-east of England during the First World War, or an academic assessment of the role of football femininity in the sociopolitical discourse.

This book attempts a more rounded picture by telling the truly extraordinary stories of early women footballers in the context both of their times and the development of football itself. We shall discover life imitating art and then art returning the compliment. Hit movies like Gregorys Girl or Bend It Like Beckham owe much (if possibly unknowingly) to the pioneering struggles of women from earlier generations.

But they also reflect the reality of those struggles being far from over. Because, as we shall see, the odd and, at times slightly disturbing, fact is that the struggle for a womans right to wrest soccer away from the jealous grasp of men, if only for the love of playing it, continued long after this country woke up to the injustice of sexism, heard the pure, clear sense of feminism, and signed into law Acts of Parliament designed to stamp out inequality.

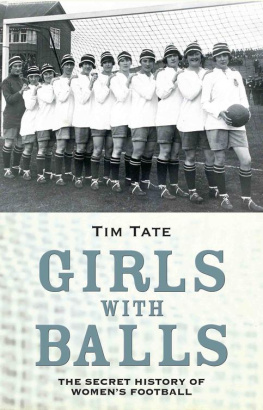

But above all this is the story of the longest-running secret in British football; a rattling yarn of determination and guts as well as jealousy, prejudice and betrayal. It is the story of devious men and girls with balls.

Tim Tate

July 2013

Boxing Day, 1920, Goodison Park, Liverpool

E verton football ground is filled beyond capacity. Fifty-three thousand men, women and children pack its stands and draughty terraces. A further 14,000 would-be spectators are locked out of the ground and line the nearby streets. The 22 players need a police escort to get into the changing rooms. Path News cameras patrol the touchline. These extraordinary crowds the biggest Liverpool has ever seen have come to watch two local rival teams play a match for charity. But this is no normal derby match, much less a standard charity fixture. Eleven of the players are international celebrities: their team is the biggest draw in British, and world, football.

Yet they are all full-time factory workers, amateurs in an increasingly professional sport, and they are all women: the Dick, Kerrs Ladies of the Dick, Kerr & Co Ltd munitions works in Preston. (The company was founded by a Mr William Dick and a Mr John Kerr, which explains the comma in the name). The male football establishment is terrified by them. And so it resolved to abolish womens football forever.

On Monday, 9 May 1881, the Glasgow Herald, Scotlands second most popular daily newspaper, carried the following report:

LADIES INTERNATIONAL MATCH

SCOTLAND V ENGLAND

A rather novel football match took place at Easter Road, Edinburgh, on Saturday between teams of lady players representing England and Scotland the former hailing from London, and the latter, it is said, from Glasgow.

A considerable amount of curiosity was evinced in the event, and upwards of a thousand persons witnessed it. The young ladies ages appeared to range from eighteen to four-and-twenty, and they were very smartly dressed. The Scotch [sic] team wore blue jerseys, white knickerbockers, red stockings, a red belt, high-heeled boots and blue and white cowl; while their English sisters were dressed in blue and white jerseys, blue stockings and belt, high-heeled boots and red and white cowl.

The game, judged from a players point of view, was a failure, but some of the individual members of the teams showed that they had a fair idea of the game. During the first half the Scotch [sic] team, playing against the wind, scored a goal and in the second half they added another two, making a total of three goals against their opponents nothing. Misses St Clair and Cole scored the first two, and the third was due to Misses Stevenson and Wright.