PREFACE

This is a small book, with small ambitions. It is a recounting and a recollection of my own travels through a very small part of the world at a very particular moment: the Leeward Islands of the northeastern Caribbean, during the second decade of the twenty-first century. The Caribbean is a region at once familiar to and remote from the experience of most North Americans, even (perhaps especially) for many of those who have themselves traveled there. While hundreds of thousands of vacationers head to the Caribbean every year, for most this means either a week at the all-inclusive resorts of Mexico and the Dominican RepublicCancun, Riviera Maya, Punta Canaor a ten-day cruise (often out of Miami or San Juan) through the Virgin Islands and down the eastern chain of the Antilles, terminating at various southerly latitudes. Nevertheless, the islands often elude such travelers.

This is a book that eschews both cruise ships and all-inclusive resorts, in an attempt to discover and articulate a different kind of travel to the region. One gets to know as little of these islands from the decks of the former, as from the eateries and golf courses of the latter. But this is not a work of history or anthropology, and I do not claim any expert knowledge of these places, beyond what the curious and attentive traveler might discover for him- or herself. Still less is this a work that looks down its literary nose at the meretricious, middle-class traveler who should just stay home if he or she lacks the resources to rub shoulders with the elite on islands like Nevis or Anguilla. I could not (and cannot) afford to keep pace with the bountiful haves who annually make the region their playground. But travel is not just about money; it is about a particular disposition born of the encounter with an unfamiliar place; ironically, money is often used to purchase the sort of comfort and familiar experiences abroad that make the trip itself superfluous. And the Caribbean islands are not playgrounds, or even destinations, they are real places, full of actual people and particular histories. One of the challenges of traveling in a region that strives so determinedly to present itself as little more than a series of luxurious resortsplaces where there is something for the entire family, but which also cater to a carefree hedonism, places where you can swim with dolphins and blast across the beaches aboard all-terrain cruisers, where you can get close to nature without setting down either your frozen cocktail or your smartphoneis that one is not often encouraged to get off the beaches and away from the resorts, so as to catch a glimpse of what the island itself is like. This is a book about traveling in a region where most of us are encouraged to simply vacation.

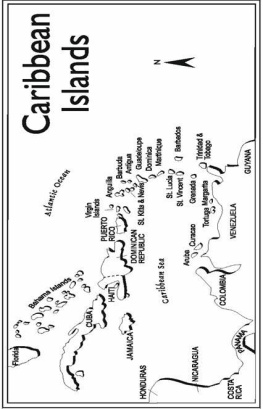

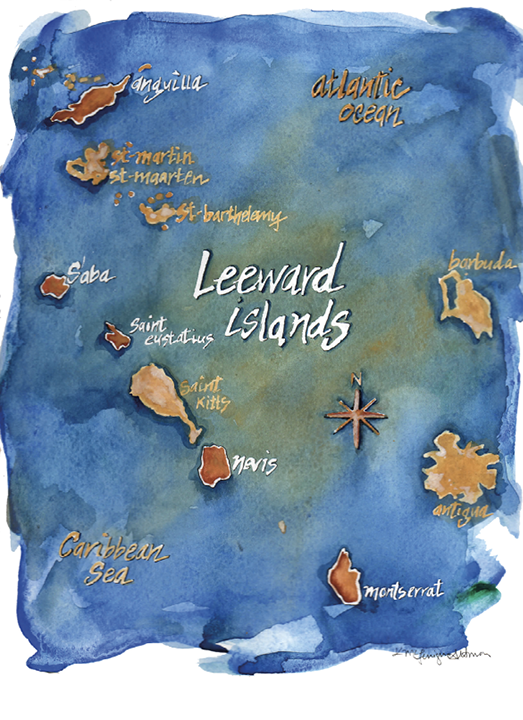

There are some 7,000 islands and thirty nations in the Caribbean. This book is about five of them. The Leeward Islands (particularly the smallest members of the archipelago) constitute my focus. There is something of a problem, however, even in the designation itself. First of all, these islands at the northeastern edge of the Lesser Antilles do not really lie to the lee at all. The Trade Winds and the equatorial currents that help to determine the balmy, breeze-befallen Caribbean climate embrace equally the Windward and the Leeward Islands; it is thus not the case, as the designation would seem to imply, that the Leewards are positioned somehow behind the Windward Islands, and thus out of the wind. The Spanish correctly referred to all the islands of the eastern Caribbean as Windward Islands, calling them Las Islas de Barlovento , while the small islands close to the South American mainlandBonaire, Aruba, Curaao, Avesthey named the Leewards ( Las Islas de Sotavento ). Likewise, the French continue to refer to all the islands of the Eastern Caribbean as Les les du Vent (Islands of the Wind).

It was the British who confused matters when they designated their own early holdings in the Lesser AntillesAntigua, St. Kitts, Nevis and Montserratas the Leeward Caribbee Islands once their collective government had been separated from that of Barbados in 1671. These were the days when sugar was rapidly transforming the islands and the planters in the Leeward group were convinced that Barbados refused to come to their aid during the Second Dutch War (16657) because its planters were only too happy to see the cane fields of their fellow countrymen devastated by the French and the Dutch, in hopes that this would drive up the value of their own Barbadian sugar. Sir Charles Wheler was the first governor-in-chief of the English Leeward Islands, but he seems to have bungled negotiations with the French for the return of lands lost by the English to their Gallic foes on the island of St. Kitts. Having lost the confidence of the planter class, he was unceremoniously cashiered and replaced by Sir William Stapletonan Irishman who successfully governed the new colony from 1672 to 1685 (and who won the favor of the Lords of Trade in London in no small measure because he was able to placate his fellow countrymen in the Leeward Islands and to convince King Charles that his Irish subjects in the West Indies were not exclusively treasonable rogues). Of course, the ascendency of sugar led also to the ascendency of slavery in the Leeward Islands and throughout the Caribbean; the horrors of the institution cannot easily be overstated. Numbers alone begin to make this clear. Whereas some 275,000 slaves were brought from Africa to what would become the United States between 1607 and the end of the eighteenth century, some 1.2 million slaves were brought to the British West Indies between 1708 and 1790 alonemore than eight times as many slaves in less than half the number of years. This discrepancy is due in part to the fact that there was an annual population loss of slaves in the Caribbean (more died than were born on the plantations) that endured for more than two centuries. By the end of the 1700s there were some 750,000 black men and women living in the United States, but well under 400,000 in the British West Indies. The Caribbean sugar estates were killing fields.