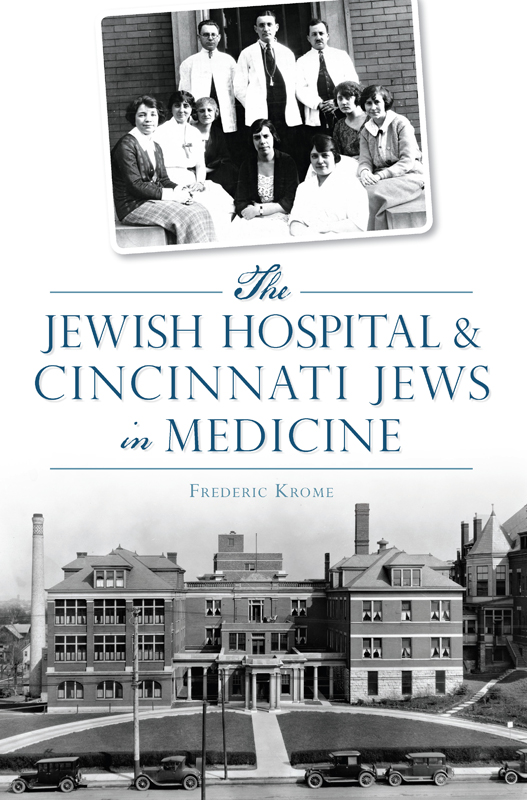

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Frederic Krome

All rights reserved

Images courtesy Henry R. Winkler Center for the History of the Health Professions unless otherwise noted.

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.593.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015945700

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.849.1

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is dedicated to John Fine, Saul Benison and Henry R. Winkler. All three were my teachers, my mentors and my role models. More than that, all three were my friends. May their memory be for a blessing.

PREFACE

For more than a century, the Jewish Hospital of Cincinnati was located on Burnet Avenue, on the border between the neighborhoods of Mount Auburn and Avondale. The complex was part of what locals often call Pill Hill, for in addition to the Jewish Hospital, the area also includes the University of Cincinnati Medical School, UC Medical (formerly Cincinnati General Hospital), Cincinnati Childrens Hospital, Shriners Hospital and a branch of the Veteran Administration Hospital. Of all these institutions, however, the Jewish Hospital was the first to locate itself in this region, arguably anchoring its development.

In 1994, the Jewish Hospital of Cincinnati was sold to the Cincinnati Health Alliance, bringing to a close its nearly 150-year history as an institution sponsored and run by the Cincinnati Jewish community. Three years later, the Hospital closed its Burnet Avenue facility and moved its entire operation to a new location in Kenwood, an upscale part of the city several miles from the urban center, thereby severing another link with its past. With the breakdown of the Health Alliance, the Hospital was subsequently sold in 2010 to Mercy Health, a Catholic organization; after this latest transfer of ownership, it seemed to some that the only thing Jewish about the Jewish Hospital was its name.

Despite the institution now being under the aegis of a Catholic organization, the Mercy Health Alliance has committed itself to maintaining the Jewish identity of the Hospital. A visitor to the Kenwood facility will see the walls of the hallway near the entranceway covered with the memorial plaques that testify to a long tradition of individual giving by members of the Cincinnati Jewish community. In the twenty-first century, patients at the Jewish Hospital have access to rabbinic chaplains and kosher foodsomething that patients in the twentieth century could not always get. Indeed, in the 1930s, when a local rabbi asked that space in the Hospital be set aside for a chapel, the president of the Jewish Hospital Association was against it, for he asked, Who would use it? In the same year, when an Orthodox rabbi demanded that kosher food be served at the Hospital, he was met with a hostile response from the board, which was more concerned with the ongoing financial crisis of the Great Depression than with adhering to religious practice.

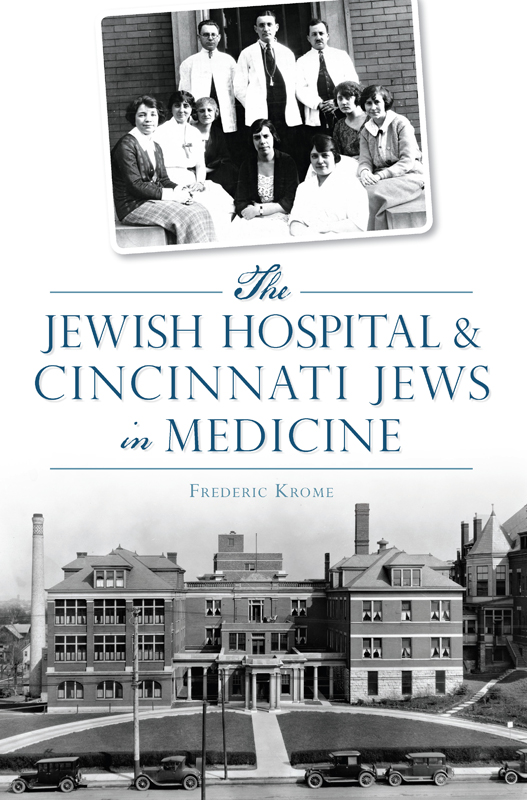

This entrance to the Jewish Hospital building was part of the 1922 expansion and was demolished in the late 1960s renovation.

It might seem surprising that an institution founded and sustained by a Jewish community was for many years not concerned with Jewish spiritual and ritual observance in its flagship medical establishment. This begs an interesting question: if the leadership was not interested in promoting these attributes of Jewish life, why then establish and maintain a Jewish hospital? Indeed, without such things as kosher food and religious observance, was the Jewish Hospital really a Jewish institution?

Sign for the Jewish Hospital at the corner of Kenwood Road and Galbraith; the Mercy Health logo is clearly visible at the lower left. Photo by author.

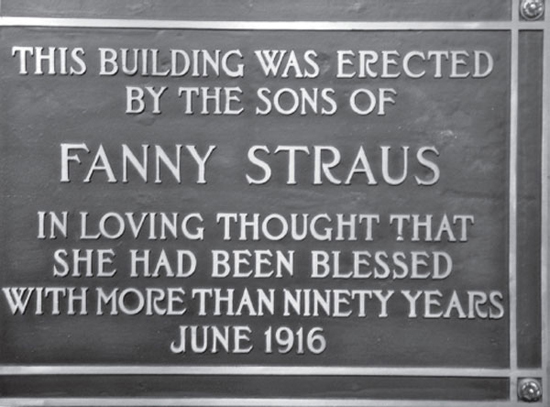

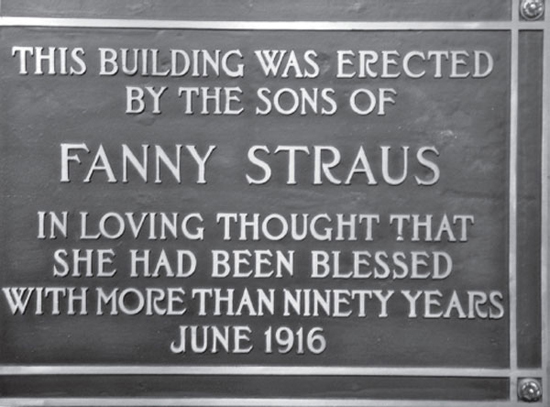

Donor plaques such as these lined the entryway of the Jewish Hospital throughout much of the twentieth century. Many were transferred to the Kenwood facility in the 1990s. Photo by author.

In order to address the question How Jewish was the Jewish Hospital? we must first set some of the historical parameters. One useful source is Daniel Bridges 1985 rabbinic thesis on the history of Jewish hospitals in the United States, written while he was a student at Cincinnatis Hebrew Union CollegeJewish Institute of Religion. Bridge listed five reasons why American Jewish communities founded their own hospitals:

They detected missionizing on the part of Christians in other hospitals.

They needed training positions for Jewish physicians.

They desired an institution that would serve kosher food and follow ritual practices.

They had concerns regarding the types of patients found in other hospitals.

They wished to imitate (and help) Christians by building similar institutions.

As we shall see in the first chapter, the desire to protect sick and dying Jews from missionaries was a major factor in the founding of the Jewish Hospital of Cincinnati. Since the Hospital was established in the mid-nineteenth century, before systematic discrimination against Jewish physicians became common, Bridges second reason does not apply. Indeed, Bridge argued that no Jewish hospital founded in the nineteenth century was created in response to this type of discrimination. While the lack of kosher food, rabbinic services and even a chapel seem to belie the Jewish character of the institution, the issue is further clouded by the fact that even during the first decades of its existence, the Hospital accepted patients regardless of ethnicity or religious affiliation. Given that only one of these five characteristics seems to apply, what then made the institution a Jewish one?

Bridges thesis provides another possible way of understanding how an institution can have a Jewish character, even without the myriad reasons for its being founded. In order to assess the Jewish character of an institution, Bridge suggested that some combination of nine attributes has to exist:

The hospital was founded by members of the Jewish community.

The hospital was built primarily for the members of the Jewish community.

The hospital was funded primarily by members of the Jewish community.

The hospital had a Jewish name.

The hospital was governed by members of the Jewish community.

The hospital was staffed by an unusually high percentage of Jews.

Next page