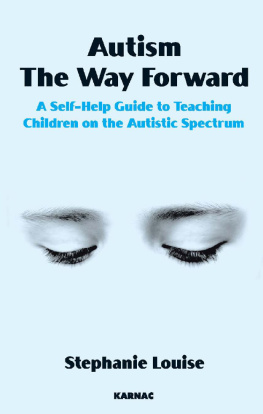

Friends

like Henry

Everything your family needs to know

about finding, training and learning

from an autism companion dog

Nuala Gardner

Jessica Kingsley Publishers

London and Philadelphia

Contents

Points to Remember When Helping a Child with ASD or

Learning Difficulties

Points to Remember When Helping an Adult with ASD or

Learning Difficulties

Foreword

JIM TAYLOR

F inding approaches or methods that will have an immediate impact and can achieve long-lasting gains can be a challenge when parents and professionals are faced with the diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). A good team of professionals working alongside a family, along with a broad-based education, will have the most positive impact on the development of young people. However, at times, added value is needed and may be sought through resources such as music therapy, physical therapies, a focus on individual enthusiasms, and others. The introduction of dogs or pets into the lives of young people with ASD and their families is an approach that has gained increasing credibility in the last number of years. As with all approaches or interventions, this is not just an easy fix, and families embarking on this route need to explore further how best to implement this approach to ensure greater and more meaningful success.

Following media stories regarding the success of introducing therapy dogs, many families have taken such a step, and the canine addition to the family has undoubtedly added to the quality of life of the whole family. The public profile of guide dogs, hearing dogs, etc. is such that we understand and acknowledge the intensity of the training that both the animal and the owner experience. What has been less clear, up until now, is the extent of the preparation and training involved when placing/receiving a dog into a family of a child with autism. This manual is therefore especially relevant as it demonstrates the authors own unique experience and the range of experiences she has had with, initially, a pilot group of eight families across the UK and beyond.

Nualas personal experience in developing partnerships with dogs, families and individuals is well documented and has provided inspiration and guidance for many families. Her own experience, as described in her first book, A Friend Like Henry , and the subsequent film version, was the first in the country to gain major exposure and publicity. Therapy dogs have since been introduced to some schools, with detailed evaluations highlighting the benefits to those involved in the programme.

My role here is not to evaluate the outcomes of such initiatives but to explore how Nuala, through the pilot programme involving eight families and her specialised approach, addresses the very specific learning styles and strengths found in autism. I will also examine the consideration Nuala gives to some of the barriers to learning for example, how the differences in interaction and the development of meaningful relationships may be addressed positively through the introduction of a specially trained dog into family life.

As with all approaches in autism, it is essential to identify and clarify what it is that makes a significant difference and what makes such approaches especially suitable for young people with ASD. Experience shows us, though, that it can be difficult to identify what it is about any approach that makes it unique to autism. This manual illustrates just how Nualas approach directly addresses the autism. For example, it outlines those elements of the young persons autism that are supported through the programme; it highlights the advantages that can be gained through the introduction of the dog into the young persons life; and, crucially, it emphasises the importance of planning, preparation and correctly matching dog to child/family in order to maximise the chances of sustainable success.

The concept of introducing a dog into a family is an attractive one and, as such, there is a risk that some families might rush into this without the adequate planning and preparation that Nuala outlines in her manual. She also advises that school-based programmes involving a therapy dog should be underpinned by a policy, procedures and, certainly, by a set of agreed aims and targets. Nualas work demonstrates how this type of planning can also be reflected in family life and how, if the experience and guidelines can be followed closely, positive outcomes can be almost guaranteed. Often, generic responses and a one size fits all approach lead to forgetting the most critical factor: that each young person is unique. In fact, the family, the experience and training of the dog, the interaction style of each individual, and the home environment are all critical factors.

Nualas success within the pilot project has been based on directly addressing these factors. As she writes, each child, each family and each dog is unique.

So what, then, are the important factors in ensuring success, in ensuring that each partnership adds significant value to lives? And how does this fit in with current thinking about autism?

First of all, it is important to stress that one of the guiding principles here is that the partnership/relationship with the dog provides opportunities for the young person to learn about many things and to acquire new skills, some of which may be challenging. For instance, skills such as learning about relationships, learning about making a contribution to a companion and family group and so on may need to be introduced and taught to the learner with autism. The case for using dogs within autism is less about compensating for the challenges and more about empowering and enabling the young person in ways which this manual illustrates.

As with all the best therapies/methodologies, the way forward should be decided upon after careful assessment. The cases and examples that follow in this manual keenly demonstrate the level of detailed information that needs to be amassed about the child, his or her life experiences and the family situation.

Before matching the dog and the child, Nualas programme takes into account the childs social understanding, the communication level and the environment that the child is living and working in. This degree of detail, especially through the transition phase, is critical. There may only be one chance to get this right, and the detail in the following pages shows the distance that must be covered. Nuala describes how important it has been to introduce her own dog, who has on many occasions played a heroic part in making immediate connections with young people! In many of her case studies, by the time a dog has been selected and has been introduced, the possibility of failure has been drastically reduced. Many of the stories from the pilot project demonstrate that the timing of the introduction of the dog into the family, the language used and the understanding of the impact of the environment are all critical.

It is impressive at this stage in the process that a strong team is created; in the case studies, the team involved Nuala, the family and, of course, the young person. Together, the team decides what the focus of the programme needs to be, as well as agreeing the precise purpose behind the introduction of the dog into the team. What is often missing from programmes for young people with autism, especially outside schools, is a clear and agreed plan for learning outcomes. It is important to stress again that this programme is not about compensating for the autism but directly addressing strengths and learning styles, developing and nurturing skills and strategies, and building on confidence and self-esteem. The transition programme is directly and effectively teaching and facilitating the development of companionship, interaction skills and strong, meaningful relationships.

Next page