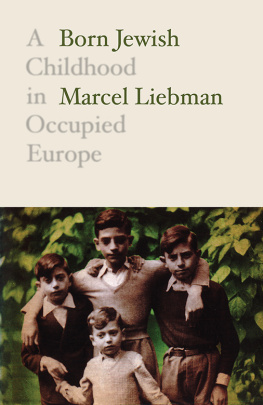

The True Story

of a Jewish Boy

and His Mother in

Mussolini's Italy

A CHILD

AL CONFINO

Eric Lamet

FOREWORD BY RISA SODI, PHD

Copyright 2011 by Eric Lamet

This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form

without permission from the publisher; exceptions are made

for brief excerpts used in published reviews.

A large portion of this material was previously published as A Gift from the Enemy by Eric Lamet, published by Syracuse University Press, copyright 2007 by Eric Lamet, ISBN 10: 0-8156-0885-3, ISBN 13: 978-0-8156-0885-1

Published by

Adams Media, a division of F+W Media, Inc.

57 Littlefield Street, Avon, MA 02322 U.S.A.

www.adamsmedia.com

ISBN 10: 1-4405-0997-2

ISBN 13: 978-1-4405-0997-1

eISBN 10: 1-4405-1126-8

eISBN 13: 978-1-4405-1126-4

Printed in the United States of America.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lamet, Eric

A child al confino / Eric Lamet.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4405-0997-1

ISBN-10: 1-4405-0997-2

ISBN-10: 1-4405-1126-8 (eISBN)

ISBN-13: 978-1-4405-1126-4 (eISBN)

1. Lamet, Eric 2. Jews, Austrian Italy Biography. 3. Jewish refugees Italy

Biography. 4. World War (19391945) Italy Jews. 5. Jewish children in the

Holocaust Italy Biography. 6. Italy Biography. I. Title.

DS135.A93L364 2010

940.5318092 dc22

[B]

2010038754

Photos from the private collection of Eric Lamet.

This book is available at quantity discounts for bulk purchases.

For information, call 1-800-289-0963.

Author's Note

T hese memoirs were inspired by a compulsion to give my children a glimpse of how their father grew up in what were arduous times, especially for European Jews. They were also written before the memory fades and the experiences endured by me and many others like me are forever lost to future generations. I have not attempted to gain the reader's sympathy, for none is deserved. I did, however, make a diligent attempt to depict, as objectively as I could, the lifestyle we experienced in Italy during the Fascist regime.

I am happy that not all that is written addresses itself to the ugliness of mankind. In the midst of all the horror of that period, there were glimmers of human goodness. Some even touched me personally.

I do not call myself a survivor, for this term rightly belongs to those brave and remarkable individuals who endured the brutalities of the German death camps. I do consider myself a remnant of what once had been the large, culturally rich Jewish community of Europe.

My odyssey lasted sixty-seven months and represents a period in my life that I would not want to relive for all the fortunes in the world. Yet, sixty years later, I very much cherish the memories.

All the individuals portrayed herein are real persons and only in a few instances, mostly because of memory lapses, have their names been changed or omitted.

With gratitude so great that words fail to adequately express it, I wish to thank the following:

My loving agent, Sally Wecksler, whose belief in me and my work made this book a reality. Sadly, fate deprived her of rejoicing in this success and seeing that her trust was justly placed;

My editor, Peter Schults, for his indefatigable and enthusiastic attention to this work and his constant encouragement;

My dear wife, Cookie, for graciously enduring the countless times I compelled her to reread the same chapters or paragraphs and for the faith she continues to have in me.

Dedicated to Lotte and Pietro Russo, for all they still mean to me.

In memory of the millions of innocent human beings who suffered and who perished at the hands of the Nazi monsters.

E ric Lamet was born Erich Lifschtz on May 27, 1930, into an upper-middle-class Jewish family. Both of his Polish-born parents moved to Vienna before the first Great War.

On March 18, 1938, five days after the Anschluss, when German troops marched into Vienna, Lamet's family fled to Italy, where he spent most of the next twelve years. When World War II ended, Lamet settled in Naples with his family. He finished high school in that city and later enrolled in the Department of Engineering at the University of Naples.

In 1950, the family moved to the United States, where Lamet continued his engineering studies at the Drexel Institute of Technology in Philadelphia near his family's home. Deciding that business was more in keeping with his personality, he embarked on a business career. Over the years he became involved in a variety of enterprises and retired as a CEO in 1992.

Fluent in German, Italian, English, Spanish, and Yiddish, Lamet served as an interpreter for the U.S. State Department and taught Italian for several years.

Lamet has three children, two stepchildren, and seven grand-daughters. He lives with his wife in Tamarac, Florida.

Contents

Foreword by Professor Risa Sodi

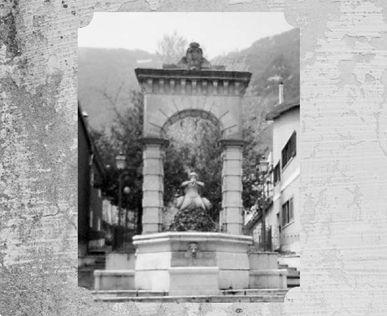

I f you travel today to the southern Italian village of Ospedaletto d'Alpinolo in the Apennine Alps east of Naples, you will find a village perched 2,200 feet above sea level and ranging over 1,400 acres, half of them rocky cliffs. Its 1,639 residents make a living today as they have for centuries: from the hazelnut and chestnut forests surrounding the town. Its 643 dwellings are interspersed with pizzerias, restaurants, hotels, and shops that provide the amenities of modern life including Internet access, as evidenced by the town's website.

Sixty-five years ago, however, when young Eric Lamet and his mother, Carlotte Szyfra Brandwein, were sent there to begin four years of compulsory internal exile, life in Ospedaletto was radically different. The terrain and the surrounding forests were essentially the same, only the population, with 1,800 inhabitants, was slightly larger than it is now. In 1940, the Fascist system of il confino (from the Italian verb confinare , meaning to confine, to relegate) had forcibly brought to the village scores of foreigners, political activists, Jews, and sundry other potential enemies of the state

Il confino was a system of enforced internal exile devised by Mussolini quite early in his regime in order to marginalize those who could potentially cause it harm. Conceived as a measure halfway between a warning and incarceration, il confino was a police procedure that required no actual trial but, rather mere denunciation by local authorities. In the years preceding 1938, the confinati were usually vocal political opponents of fascism; indeed, the most prominent anti-Fascist thinkers of the day ended up in internal exile, mainly on Italy's countless small islands. There, they were divorced from political events, deprived of the means to communicate with the mainland and settled among generally indifferent or non-politicized local populations. The Communist theoretician Antonio Gramsci, the Socialist leader Pietro Nenni, and the liberal thinkers Giovanni Amendola and Piero Gobetti all were sent into internal (island) exile before 1938.

The mechanism of il confino was quite simple: Those affected were required to remain within a certain area (usually within the town limits) and to sign in daily at the local police station. They were responsible for finding their own housing and providing their own means of support aside from the stipend provided from the Fascist government. Correspondence was censored, and in many locales gatherings of confinati were banned. In1938, in an effort to appease Hitler and keep pace with his German ally, Mussolini promulgated a series of racial laws applied specifically to Italy's Jewish population.

The native-born Italian Jews, spread among several dozen central and northern Italian communities, worshiped in either the Italian or the Sephardic rite. They fell mostly into the middle class (though there were notable wealthy families, such as the Olivettis of Ivrea, as well as pockets of desperate poverty, especially in and around Rome) and were extraordinarily assimilated into Italian political, cultural, and everyday life. The Fascist racial laws directed at them were at once overarching and picayune, vexatious, and devastating. As of autumn 1938, for example, Jews were forbidden from marrying Aryans (non-Jewish Italians), from holding any sort of state job, serving in the military, or employing an Aryan domestic, or even from owning land over a certain value or a factory with more than a certain number of workers. Jews could not list obituaries in their local newspapers or own a radio. Jewish students were banned from public schools, including the universities and Jewish teachers, attorneys, doctors, and others were banned from their professions. Exemptions were allowed within certain limits; nonetheless, the impact on the Italian Jews both psychological and material was crushing.