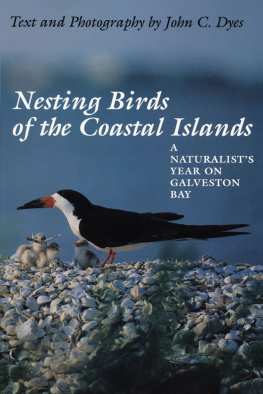

John Dyes - Nesting Birds of the Coastal Islands: A Naturalists Year on Galveston Bay

Here you can read online John Dyes - Nesting Birds of the Coastal Islands: A Naturalists Year on Galveston Bay full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, publisher: University of Texas Press, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

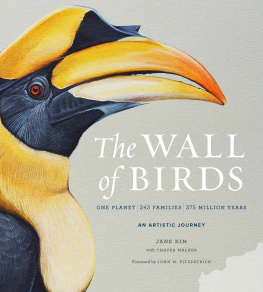

- Book:Nesting Birds of the Coastal Islands: A Naturalists Year on Galveston Bay

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Texas Press

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nesting Birds of the Coastal Islands: A Naturalists Year on Galveston Bay: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Nesting Birds of the Coastal Islands: A Naturalists Year on Galveston Bay" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

John C. Dyes presents a year in the life of the birds on the Texas Coast.

John Dyes: author's other books

Who wrote Nesting Birds of the Coastal Islands: A Naturalists Year on Galveston Bay? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Nesting Birds of the Coastal Islands: A Naturalists Year on Galveston Bay — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Nesting Birds of the Coastal Islands: A Naturalists Year on Galveston Bay" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Number Twenty-Two

The Corrie Herring Hooks Series

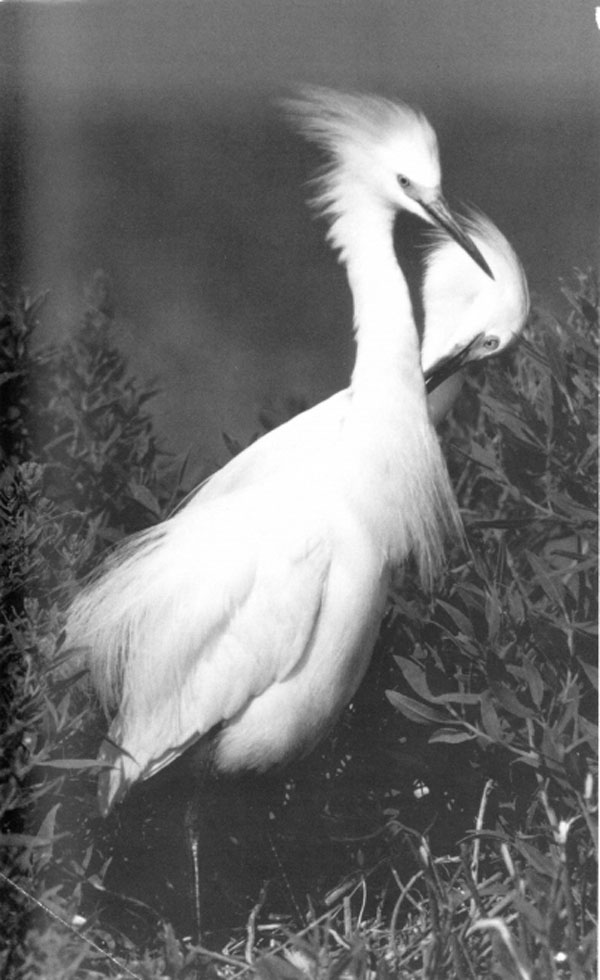

The Snowy Egret in the foreground shows off its breeding plumage while its mate in the background preens itself.

Text and Photography by John C. Dyes

Nesting Birds of the Coastal Islands

A NATURALISTS YEAR ON GALVESTON BAY

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS

AUSTIN

Copyright 1993 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

First edition, 1993

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, University of Texas Press, Box 7819, Austin, TX 78713-7819.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dyes, John C. (John Clifton), date

Nesting birds of the coastal islands : a naturalists year on Galveston Bay / text and photography by John C. Dyes. 1st ed.

p. cm. (The Corrie Herring Hooks series ; no. 22)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-292-71567-6 (alk. paper)

1. CiconiiformesTexasGalveston BayNests. 2. CiconiiformesTexasLaguna MadreNests. 3. CharadriiformesTexasGalveston BayNests. 4. CharadriiformesTexasLaguna MadreNests. 5. Barrier IslandsTexas. 6. CiconiiformesTexasGalveston BayNestsPictorial works. 7. CiconiiformesTexasLaguna MadreNestsPictorial works. 8. CharadriiformesTexasGalveston BayNestsPictorial works. 9. CharadriiformesTexasLaguna MadreNestsPictorial works. I. Title. II. Series.

QL696.C5D94 1993

598'.34'09764139dc20 92-29457

ISBN 978-0-292-75897-1 (library e-book)

ISBN 978-0-292-75898-8 (individual e-book)

DOI: 10.7560/715677

TO MY WIFE, ALLENA, WHO BELIEVED IN THIS PROJECT

Preface

The young Laughing Gull, in its nest on Little Pelican Island, feels very secure protected by the surrounding grasses.

In this book I follow twenty-two species of colonial wading birds, gulls, and terns through a one-year nesting cycle. The term colonial is used for birds that nest in groups ranging from a half-dozen to tens of thousands or more. Ornithologists are not sure whether the prime reason for gathering in the large colonies is to pass information on to the young birds or to find safety from predators. Both theories may be correct. Herons feed alone, Roseate Spoonbills feed in flocks, but the young of both may rely on the adults to show them where and how to feed. The safety from predator theory may also be true since the colonial birds return yearly to the islands with no predator problems.

This group of birds caught my interest for a combination of reasons. I have been an out-of-doors person all my life and have been photographing nature for more than thirty years. I was a chemical engineer and worked in a refinery for many years, but consider myself to be an active environmentalist and am a member of the National Audubon Society, the Sierra Club, and the Nature Conservancy. I love birds in general but am color blind and have difficulty identifying many perching birds. However, the wading birds, gulls, and terns are no problem. And, perhaps through my Viking ancestry, I inherited a love of salt water and everything associated with it. I was introduced to the colonial birds by Elric McHenry, one of the Houston areas top birders, when he asked if I wanted to take part in the annual Texas Colonial Waterbird Census conducted by the Texas Waterbird Society. Since I had a boat, I could provide transportation to the islands in the southern part of Galveston Bay where we were to conduct our survey. I was simply bowled over when I saw the amount of nesting right in my local area and started going back on my own to photograph. With this introduction and the combination of factors in my background, this book project clicked into place. All the nesting is on islands, so I use a 20-foot lightweight, shallow-draft boat for transportation.

The observations and photographs were made in the Galveston Bay and Laguna Madre areas over an eight-year period and then, for the purposes of this book, condensed into a one-year period. Although the photographs were taken within a rather limited geographical range, the birds being photographed have much wider ranges. Some, like the Reddish Egret, breed only on the Gulf Coast south to Central America, while others, like the Great Egret, breed worldwide.

On the Texas coast the birds have an extended nesting period, but their season is like a bell-shaped curve. The birds nesting year starts in February, builds during March and April, reaches a crescendo around the first of June, then declines rapidly to end, for all practical purposes, in July. A few stragglers may still be around in August and September. In the warm southern rookeries there is a great deal of overlap within species. For instance, one group of White Ibis may start nesting in March and have their young raised by June while elsewhere another group will be starting nests in June.

Since no one island in the Galveston Bay area supports all the birds covered in this book, I photographed on eight different islands, some of which are natural. Others are spoil islands, that is, human-made islands that were built from materials dredged up during the building of the Intracoastal Waterway and other ship and barge channels. Human-made islands have been the birds salvation. Several of the birds, like the Least Terns and Black Skimmers, once nested on the beaches. When people, with their automobiles, children, dogs, and cats, discovered the beaches, the birds were forced to move to the islands. Also, there were at one time large inland heron and egret rookeries, but most have been developed out of existence, forcing these birds onto the islands. For the most part, the islands provide excellent nesting habitat near good feeding grounds. Of all the nesting islands in the Galveston Bay area, only three, North Deer, Rollover Pass, and Vingt-et-un are National Audubon Society (NAS) sanctuaries where wardens keep a daily watch to protect the birds from sightseers.

Due to budget constraints in the past, the colonial wading birds have received little active attention from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. But, at this writing, the TPWD is expanding its nongame species programs. It is developing plans to identify rookery areas, improving habitat to maintain species diversity, and removing predators from nesting sites, in an effort to manage twenty-five species of colonial water birds in Texas. Funds have been allocated to monitor Brown Pelican and Reddish Egret populations on the Central Texas coast, and interior Least Tern and Cattle Egret populations elsewhere. And, with census figures gathered during the yearly Texas Colonial Waterbird Census, the TPWD monitors populations and population changes from year to year.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) is also increasing its efforts to protect the colonial wading birds, by participating in the Texas Colonial Waterbird Census, monitoring populations and population changes, and working in conjunction with the Corps of Engineers to use the dredged material from the maintenance of the Intracoastal Waterway and other ship channels to build new nesting islands or rebuild islands that have suffered erosion.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Roseate Spoonbills, and several of the egrets, terns, and gulls were driven almost to extinction by plume hunters and egg gatherers. After laws were passed banning these practices, the birds were able to reestablish, their populations because large wilderness areas existed. Today in the continental United States only token wilderness areas exist. None are large enough to be self-sustaining; all require human intervention. National Audubon wardens patrol their islands, but on other islands, the birds have to fend for themselves and are often disturbed by anglers, campers, and sightseers. Increasing population pressure and new problems, such as fire ants, require that this group of birds receive active attention from government agencies and also the care and concern of every person who uses and enjoys the out-of-doors.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

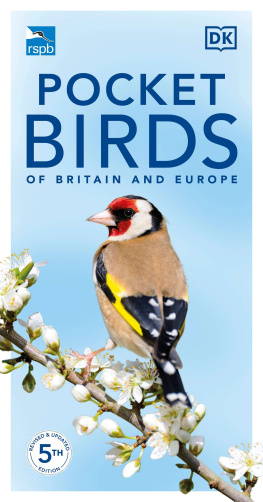

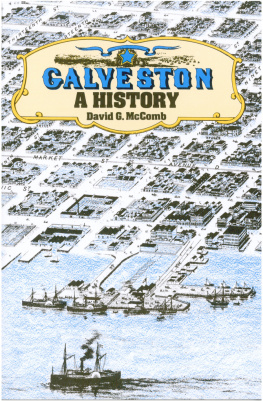

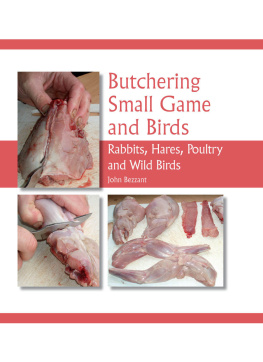

Similar books «Nesting Birds of the Coastal Islands: A Naturalists Year on Galveston Bay»

Look at similar books to Nesting Birds of the Coastal Islands: A Naturalists Year on Galveston Bay. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Nesting Birds of the Coastal Islands: A Naturalists Year on Galveston Bay and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.