All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from InterVarsity Press.

While any stories in this book are true, some names and identifying information may have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

The publisher cannot verify the accuracy or functionality of website URLs used in this book beyond the date of publication.

FOR MY NEIGHBORS.

Thank you for trusting me to tell this story.

Foreword

Michael Frost

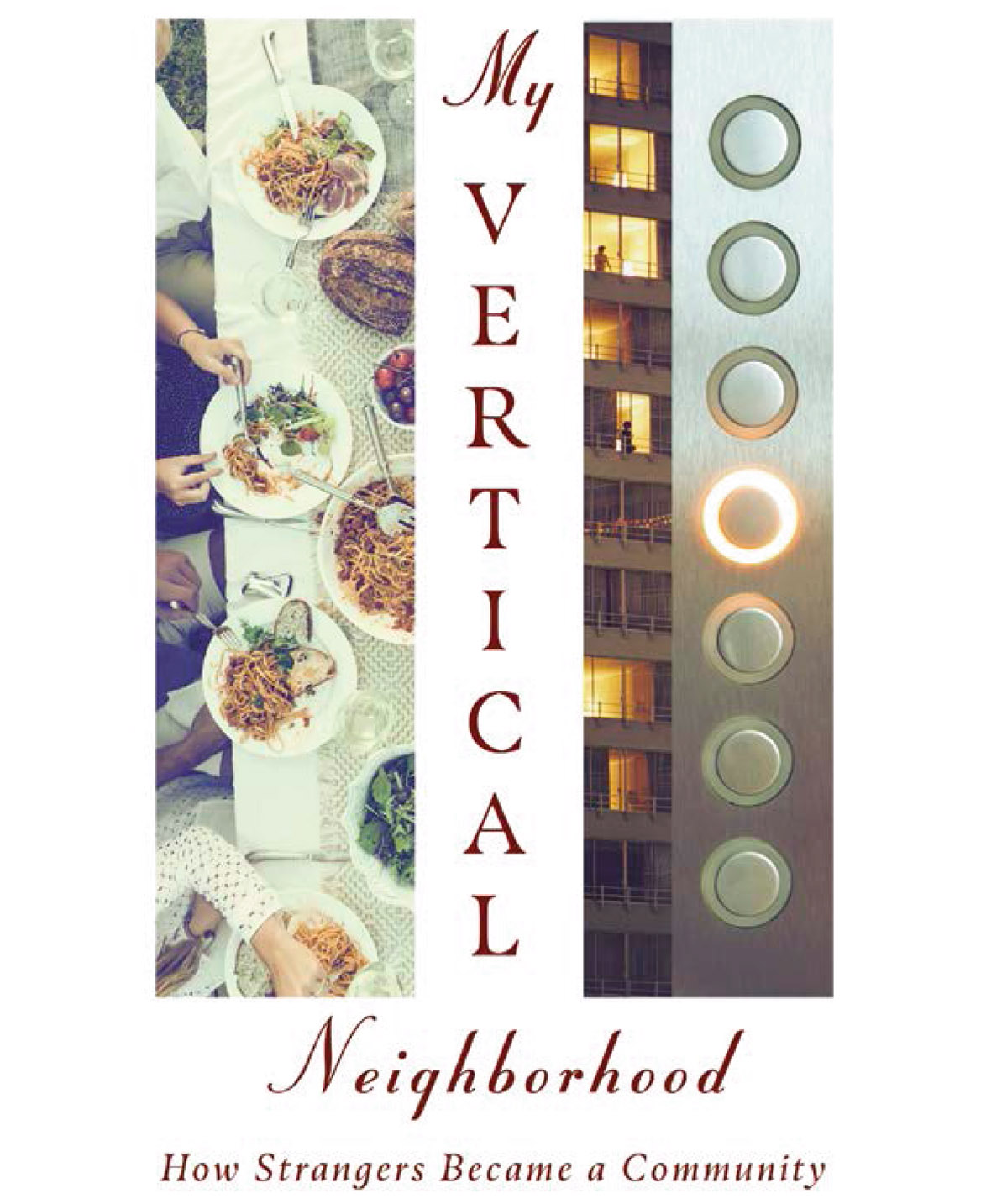

I n My Vertical Neighborhood, Lynda MacGibbon tells the story of leaving her charming three-bedroom Cape Cod house with a knotty crab apple tree and a towering poplar in the quiet town of Moncton, New Brunswick, to move into the hustle and bustle of high-rise living in Canadas largest city, Toronto. It sounds like Green Acres in reverse. Remember that whimsical show about a Park Avenue couple relocating to a dilapidated farm in Hooterville only to discover a charming sense of community among the quirky locals? Its a story played out in movies such as Sweet Home Alabama, Doc Hollywood, and Hope Floats.

However, depictions of rural people moving to the city are rarely so cheery.

When filmmakers imagined urban life in the twenty-first century, it was as far from Green Acres as you could picture. From Fritz Langs Metropolis to Back to the Future and Blade Runner, the city was often depicted as a dark, wet, Orwellian dystopia of high-density living, soaring buildings, and freeways (and, of course, flying cars). Moreover, in other films about country folk forced to relocate to the city, the urban landscape is depicted as an unsafe zone where people feel anonymous, uprooted from their usual support structures, and disconnected from the rhythms of the seasons and the traditions of family or clan.

We love stories about city folk moving to the country and reconnecting with people and the earth and being drawn back into life. But we dont think life is found in the city, much less in urban high-rise developments. Philosopher Zygmunt Bauman described the individual lost in the hubbub of urban life as

a pilgrim without a destination; a nomad without an itinerary... [who] journeys through unstructured space; like a wanderer in the desert, who only knows of such trails as are marked with his (sic) own footprints, and blown off again by the wind the moment he passes the vagabond structures the site he happens to occupy at the moment, only to dismantle the structure again as he leaves.

Hes describing a sense of never-quite-belonging; that feeling where you owe the community nothing and they owe you nothing in return; where your roots dont go down very deep into the soil; where you can relocate at the drop of a hat because all apartments are alike and all neighborhoods are roughly the same. They are nomadic and never-placed. They try to smile through it all and say things about how they can bloom wherever theyre planted, but the only plants that can do that are grown in a soulless factory greenhouse.

After over two hundred years, youd think wed be better at addressing the impact of industrialization and urbanization on traditional beliefs and structures and human well-being, but as Ann Morisy puts it, We are living in troubled times and people have become bothered and bewildered. And when people become bothered and bewildered, great caution is needed because our instinctive response is scapegoating and death-dealing.

Since Morisy wrote that, the world has been hit by the cataclysmic effects of climate change and the stultifying consequences of a global pandemic. People are bothered and bewildered, alright.

Little wonder that in American cities such as Minneapolis, Ferguson, Baltimore, and Oakland, peaceful protests against racism and police brutality have recently erupted into riots, looting, and arson. Urban living can foster a sense of alienation and rage anyway, but when you throw in social need, discrimination, and racism, people explode. And the authorities respond in the only way they know howwith riot gear, tear gas, sound cannons, police dogs, concussion grenades, rubber bullets, pepper balls, wooden bullets, beanbag rounds, Tasers, pepper spray, and armored vehicles.

Of course, with the collapse of the rural sector, people pour into our large population centers looking for work and educational opportunities, for better healthcare options, and for the perceived tolerance of alternate and diverse lifestyles.

However, none of that explains why Lynda MacGibbon moved into her Toronto apartment.

She felt called.

If city dwellers are indeed bothered and bewildered, easily given to scapegoating and death-dealing, we need people like Lynda, who are willing to leave their Cape Cod homes and move into high-rise buildings to embody the love of God in that place.

I have a friend who defines the church as Christians in the neighborhood who are joining in Gods dreams for that place, and thats what Lynda describes in this book. We know Gods dream for a neighborhood does not include social isolation, disconnection from the earth, racial division, poverty, and fear. Scripture reveals that Gods dream is for a beautiful redeemed world, filled with justice, where human beings are reconciled to God and with each other, where sickness, disease, violence, and greed are no more. This means that Gods people are to move into neighborhoods (both physically and relationally) and partner with their neighbors in seeing this dream take form.

In his book Everywhere You Look, Tim Soerens commends Christians to not only care about their neighbors, but also to seek the shalom of everyone and everything in their neighborhood. In so doing, he believes they form the connective tissue that brings hope and healing to our divided society. But, interestingly, he says such a project will not be completed by those with a savior complex who wade into neighborhoods with promises to fix and heal everyone. No, Soerens says, it begins by