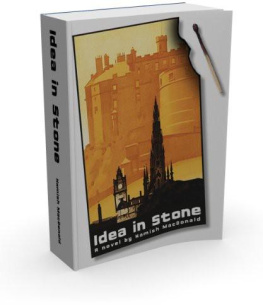

Can you be a patriot and yet pass your countrys secrets to a foreign power? This thrilling and moving book by his son shows how James MacGibbon, a highly placed British officer, supplied the Soviet Union all through the Second World War with the most precious of all secret intelligence about German military plans the product of Britains codebreakers. MacGibbon, a middle-class communist, took no money for it; was outraged that the British were risking defeat by withholding information from the ally who was bearing the main brunt of the war. It was in the Moscow archives that Hamish MacGibbon discovered how immensely important his father had been to the Soviet war effort. His rich, deeply researched and well-written book ranges from his own childhood in the convivial world of Londons left-wing intellectuals to fascinating transcripts from years of phone-tapping and surveillance by the security teams watching the MacGibbons by day and night. A story to be read by anyone who wants to understand the moral maze of espionage in the prelude to the Cold War.

Neal Ascherson

Hamish MacGibbon has written a thrilling account of English charm and Russian espionage, of politics and passion. Its also a portrait of a marriage and a window onto a fascinating period of European history viewed through the eyes of two intelligent, sensitive, unashamedly partisan witnesses.

Lara Feigel, author of The Love Charm of Bombs and The Bitter Taste of Victory

This is the remarkable account of a man who was a British patriot, but also a spy whose left-wing idealism led him to pass key war secrets to the Russians, and who, despite the best efforts of MI5, was never exposed. Hamish MacGibbon tells the story of his charming, passionate, and in some ways delightfully naive father James, set against the great events of the twentieth century, and the war which led him to become a foreign agent as significant and almost certainly more effective than any of the Cambridge spy ring.

Magnus Linklater

The author remembers his father as an affable, well-born, and nicely rumpled literary publisher, and then realises, many years later, that he was probably the agent who tipped off Stalin about the date of the D-Day landings... a brilliant and moving voyage of discovery.

Professor Patrick Wright, Kings College, London, author of The Tank and Passport to Peking

Published in 2017 by

I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

London New York

www.ibtauris.com

Copyright 2017 Hamish MacGibbon

The right of Hamish MacGibbon to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Every attempt has been made to gain permission for the use of the images in this book. Any omissions will be rectified in future editions.

References to websites were correct at the time of writing.

ISBN: 978 1 78453 773 9

eISBN: 978 1 78672 263 8

ePDF: 978 1 78673 263 7

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

To Janet and Robert

Contents

List of Plates

Unless stated otherwise, images are from the authors family archive.

Jamess parents first car.

MacGibbons and Howards at Bamburgh.

James and his mother at Fettes College.

Berlin, 1933.

Harry Pollitt in Moscow, 1924. (Peoples History Museum.)

Bob Stewart, 1922 election poster. (Peoples History Museum.)

British Union of Fascists rally, Hyde Park, 1933. (Alamy.)

Molotov signing the SovietGerman Non-Agression Pact. (Alamy.)

Jean: engagement portrait.

Jean c.1949.

Major James MacGibbon, 1944.

Commander George MacGibbon, 1942.

Ivan Kozlov, Assistant Soviet Military Attach in London during the war. (Russian public domain.)

Ivan Sklyarov, Soviet Military Attach in London, unofficially GRU station head. (Russian public domain.)

Lev Sergeev, GRU Station Chief in Washington during the war. (Russian public domain.)

Lt General Ivan Ilichev, head of GRU in Moscow. (Russian public domain.)

Harry Pollitt supporting the Allied war effort, 1942. (Peoples History Museum.)

Stalingrad. (Alamy.)

The Battle of Kursk. (Alamy.)

Mulberry Harbour. (Alamy.)

Tehran Conference, 1943. (Getty Images.)

V2 rocket damage in London.

Jamess address in Washington. (Library of Congress.)

New York, mid-1940s. (Alamy.)

The MacGibbon home, 30 St Anns Terrace. (Robin Farrow.)

Jim Skardon, MI5s chief interrogator.

The Lamb public house. (Robin Farrow.)

Trevelyan Boat Race party, 1946.

MacGibbon & Kees first list.

James at MacGibbon & Kee, 1955.

Emma Smith by the River Seine. (Getty Images.)

James sailing with Emma Smith. (Getty Images.)

James and Jean in Devon, early 1970s.

James on Pentoma.

Acknowledgements

My parents left memoirs and letters, without which this account of their earlier lives and Jamess espionage would have been impossible. I owe a great debt to Mary-Kay Wilmers, who set the project on its way by printing the essentials of the spy story in the London Review of Books (and for her consummate editing of the piece). My gratitude to Paul Richardson, who urged me to write a wider account set in the context of my parents lives, and provided wise advice and encouragement throughout. Also to Michael Thomas, whose enthusiasm for my bulky first effort made me feel it was worthwhile to keep going. My thanks to Emma Smith, who provided seminal information about the early days of MacGibbon & Kee and her own experience as the firms first author, and for her continuous professional support for the project. My thanks, too, to Magnus Linklater of The Times, to whom my father told his story, and who maintained his vow of silence until some time after Jamess death when, to spike an unreliable report from another paper, he published a meticulously faithful account. It was a privilege to have the benefit of Karl Millers famous editorial scrutiny line by line (while he was seriously ill in bed). Jane Miller generously applied her editorial skills in recommending changes to structure and to cutting over-long quotations in the interests of a more fluent narrative; a huge improvement. Paul Preston generously applied his expert knowledge to correct and amend passages in the Spanish Civil War chapter. Lucy Beaurin expertly keyed into Word facsimile documents and handwritten letters. Tom Cabot skilfully designed the complicated Soviet facsimiles to make them much clearer. My wife Renata was a source of wise advice and warm encouragement throughout.

For the crucial Soviet military intelligence perspective, central to the point of the book, I am deeply indebted to Svetlana Chervonnaya for sharing her incomparable knowledge of GRU activities and records, as well as Soviet espionage in the USA, plus many hours of detailed historical and editorial advice, given to me with meticulous application and boundless enthusiasm, not least during my visit to Moscow where she obtained entry into the Molotov Archives and translated micro-filmed documents for me. Her guided tour of Moscow, my first visit, enriched by her historical knowledge, on its own justified the trip.