To the members of the Stonewall Chorale in New York City. Hundreds of test batches later, youre still first in the nation.

A MATCH MADE IN HOLLAND

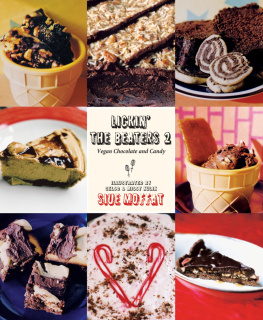

D oing cooking demos and teaching classes around the country, weve learned one thing: no one ever tires of chocolate.

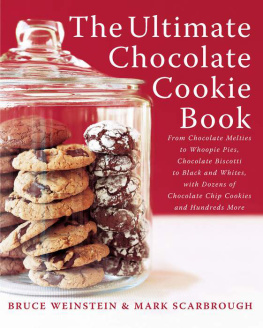

No wonder then that sometime during a demo at the International Chocolate Show in New York City, the idea hit us for an ultimate chocolate cookie book. We were making a particularly decadent treat: brownie turtle sundaesbrown sugar brownies, truffle ice cream, caramel sauce, and pecan bark. Somewhere between the brownies and the bark, we must have had the worlds first joint beatific momentwe already knew we wanted to write a cookie book, but why waste time on anything that wasnt chocolate?

For a while after that, we lived in a kind of chocolate Paradise: bittersweet, semisweet, chips, melted, grated, chopped. We had chocolate chip cookies galore, macaroons and chocolate sandwich cookies, biscotti and chocolate tea biscuits, whole trays of them, cooling on the counters and the dining room table, then rather unceremoniously dumped into plastic bags and brought to friends all across New York City. Not once did anyone turn us down.

Chocolate and cookies. Its a match so natural, so obvious, its hard to believe how modern it is. 1828, in fact. We can thank a Dutch chemist, Coenraad Johannes Van Houten, for almost every recipe in this booknot the recipes themselves, mind you, but the mere fact that they exist.

Before Van Houten, chocolate was almost exclusively a drink, hot or cold, express from the New Worldnot hot chocolate as we now know it, with warm milk; but a drink made with water, thick and bitter, like coffee, made by stirring the ground chocolate into hot water, and then drinking it without straining it. The Maya and Aztecs combined the fermented, ground chocolate beans with maize, spices, and water, then poured the concoction from a great height into smaller pots, thereby creating a muddy beverage with a viscous foam.

The conquistadors and other colonialists simply followed suit. After much ecclesiastical debate, Europeans developed a taste for this thick sludge (no maize for them, but other thickeners, like farina) and its heady foam (no pouring eitherthey beat the mixture with a small wooden whisk). However, they made one telling innovation. By the 1500s, sugar was a Western craze. So they sweetened the drink, now perfumed with everything from vanilla to musk(!), and drank to their hearts content. Chocolate was soon the beverage of choice in the Spanish court. Versailles was known to have a never-ending string of pots and chocolate service at all hours. And chocolate houses (the forerunners of coffeehouses) sprang up thick and fast in Londons central business district.

The royals and businessmen were quaffing a greasy, grainy mess. First, the chocolate they used didnt dissolve; even powdered, it fell out of suspension and ended up at the bottom of the cup (again, like grounds in coffee). Second, chocolate naturally contains cocoa butter. This fat also didnt hold in suspension; it rose to the top of the drink, making an oily slick in the foam. To make matters worse, the cocoa butter itself had often gone rancid from improper storage and unscrupulous additives. It wasnt exactly savory fare. No wonder a stern, no-funny-business chemist from Holland was so interested in perfecting this prize from the New World.

Van Houten solved all these problems: fat, taste, and texture. He perfected a machine that could extract most of the cocoa butter from chocolate, thereby making a dry cake that could be pulverized without the attendant greasethus, what we now call cocoa powder. And he added an alkali to chocolate, thereby making it considerably darker in color but far less bitter in taste, as well as better able to mix in waterthus, what we now call Dutch-processed cocoa powder.

For our purposes, its a strange and wonderful coincidence that a Dutchman came up with the first truly usable and palatable chocolate. The Dutch, of course, are purported also to be the inventors of cookies. The very word cookie most likely comes from a Dutch word, kookje, or small cakeor (more accurately) test cake, for a kookje was that bit of batter thrown onto the floor of an oven to test the heat. If the batter just sat there, the oven needed more time to heat up; if the kookje burned at the edges, the oven needed time to cool down. So we have the chocolate and we have the cookies in one countrybut we dont yet have a chocolate cookie. That divine combination still had to wait.

Van Houtens cocoa-making process had an unwitting by-product: cocoa butter and lots of it. Manufacturers now had an excess which they could sell (many still do) to the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries. But surely there was something one could do on a culinary front with that luscious left-over.

Pump it back into chocolate, of course. And that idea arose in a country that practically invented the sweet tooth: Great Britain. Less than twenty years after Van Houten applied for his patent, an enterprising Quaker businessman, Joseph Storrs Fry, already the owner of a small chocolate concern, discovered that he could mix sugar and cocoa solids with melted cocoa butter and create a thick, luscious mixture that could be molded and hardenedin other words, the worlds first chocolate bar.

But baking with chocolate still proved an elusive notion. Sure, people had cooked with chocolate before. The Marquis de Sade, trapped in the Bastille, sent endless letters to his wife, imploring her to have their personal chef send chocolate cakes while he waited for his trial. But these concoctions were rarities, not the norm. Chocolate was a drinkperiod. An aristocratic, elitist drink. Any use of it in ordinary baking would cross well-established boundaries. (Heaven forfend, thats what de Sade did!) It would take the thinking of someone who didnt follow the rules. The kind of thinking Americans excel at.

The first breakthrough happened in 1912. The National Biscuit Company (aka Nabisco), looking for a follow-up hit to Barnums Animal Crackers, introduced two chocolate disks sandwiching a cream filling: the Oreo, the first chocolate cookie craze. Lines were said to form at markets well before dawn as people waited for the next shipment of what has since become the best-selling chocolate cookie ever, with more than 7.5 billion sold each year.

But the real conflagration for home bakers came in 1930 when Ruth Wakefield made culinary history with the first chocolate chip cookie. One afternoon at the Toll House Inn in Whitman, Massachusetts, Wakefield cut up a chocolate bar, dropped it in her butter cookies, and invented an icon. But this was no happy accident. Wakefield was an entrepreneur who ran one of the most successful tourist businesses on the East Coast; she was also a trained nutritionist. Nestl had sent her bars of chocolate because the company was looking for a new sensation, something that would market their product to new heights. Ruth willingly obliged. And the rest? As they say, its history.

Its a short hop from Oreo and Tollhouse cookies to a book like this, dedicated to the chocolate cookie in all its forms, whether made with cocoa powder or melted chocolate. We hope these are recipes you can come back to time and againloads of chocolate chip cookies (believe it or not, the Vegan Chocolate Chip Cookies are our favorite), lots of sandwich cookies, some down-home treats like Chocolate Marshmallow Cookies (our version of Mallomars), and even a few foofy treats like Chocolate Tuiles. Soon, youll be doing your own demosin front of your kids, friends, or family. And youll learn the same thing we did: no one ever tires of chocolate, especially when its in cookies.

A Word About This Book

Next page