Naming the World

Naming the World

Language and Power Among the Northern Arapaho

Andrew Cowell

The University of Arizona Press

www.uapress.arizona.edu

2018 by The Arizona Board of Regents

All rights reserved. Published 2018

ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-3855-3 (cloth)

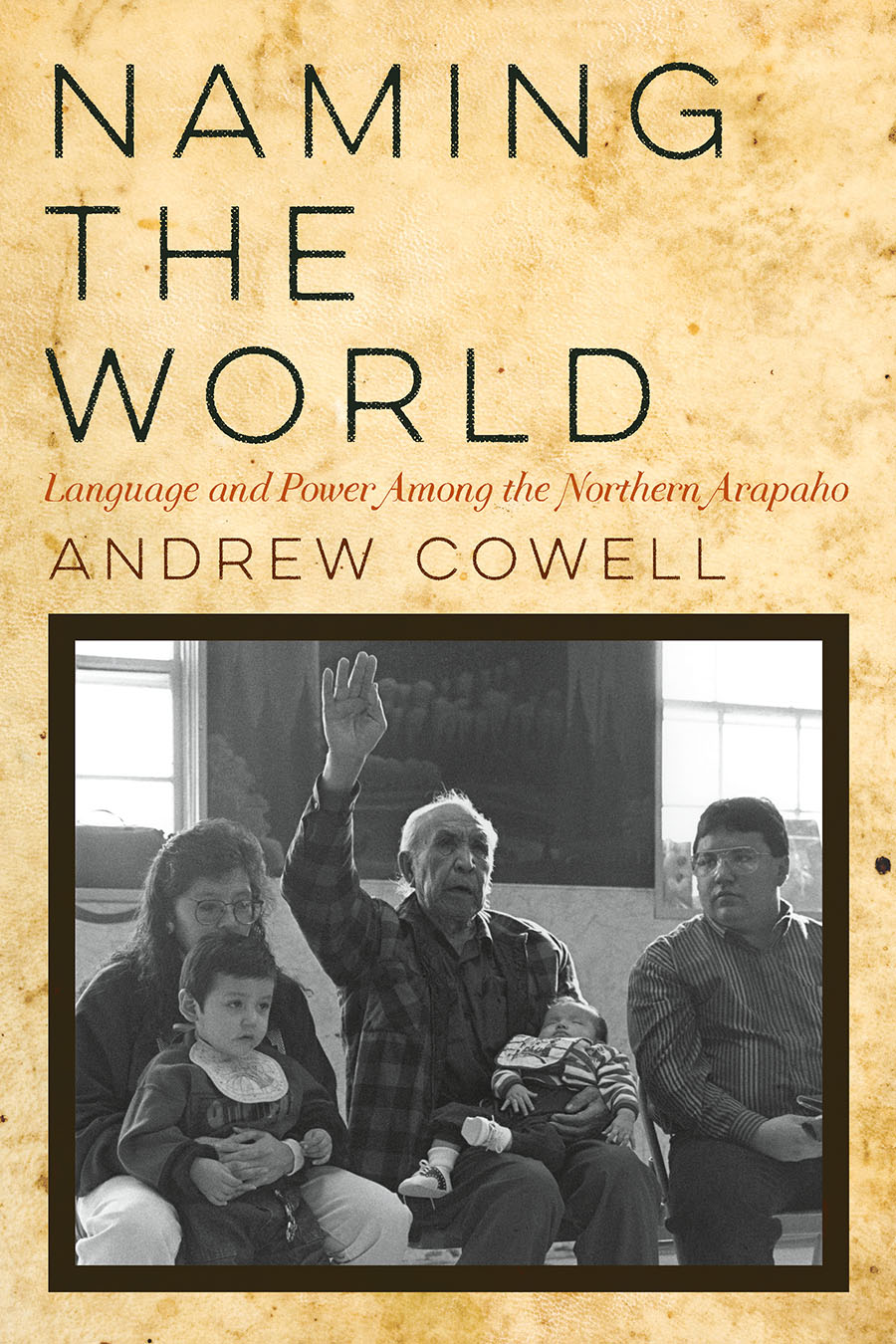

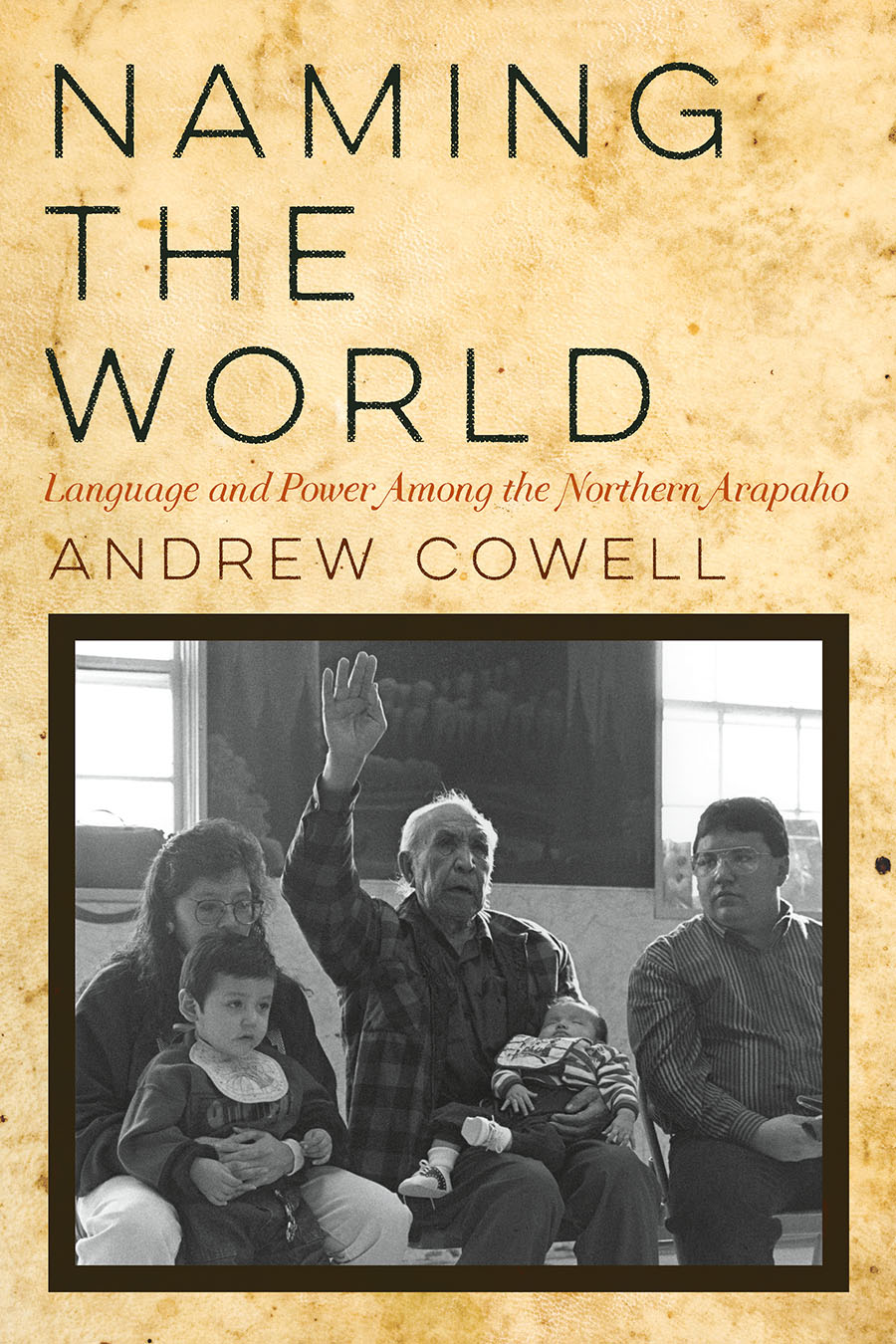

Cover design by Carrie House, HOUSEdesign llc

Cover photo: The Name Giving by Sara Wiles

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data are available at the Library of Congress.

Printed in the United States of America

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

Acknowledgments

I would of course first like to thank the people of the Northern Arapaho Tribe who have hosted me over the years, especially adopted family members. Many thanks to those who have spent time helping me learn about the Arapaho language as well as the world of Wind River, and special thanks for their willingness to be audiotaped and videotaped, which has greatly enriched my understanding as well as the completeness of this book. Secondly, I would like to thank Sara Wiles for many interesting conversations about the society of Wind River, and she and her husband Steve for hospitality over the years, which has greatly decreased the cost of my fieldwork. Speaking of costs, I note that this research was funded in part by a sabbatical year fellowship from the American Council of Learned Societies, a fellowship from the University of Colorado Council on Research and Creative Work, a Major Documentation Project grant from the Hans Rausing Endangered Languages Documentation Programme, and a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities/National Science Foundation Documenting Endangered Languages program, plus two sabbatical semesters from the University of Colorado. Earlier versions of parts of have been published in Anthropological Linguistics (Cowell and Moss 2003) and the Papers of the Algonquian Conference (Cowell and Moss 2004b), respectively. Finally, many thanks to my wife, Puahau Aki, and son, Kawena Cowell, for putting up with all my absences during fieldwork as well as providing their own indigenous inspiration for my work. Mahalo!

Abbreviations and Symbols

*: unattested proto form (Proto-Algonquian)

<: derives from

>: changes into

=: has meaning of

: first person

: second person

: third person

: third person inanimate

AC: Arapaho Culture

AI: animate subject intransitive verb

BIA: Bureau of Indian Affairs

COP: community of practice

ELAR: Endangered Languages Archive

excl.: exclusive

II: inanimate subject intransitive verb

incl.: inclusive

lit.: literally

MTH: more-than-human

NA: noun, animate

NALCC: Northern Arapaho Language and Culture Commission

NI: noun, inanimate

P: (in Arapaho transcriptions) indicates midword pause or break by speaker

PA: Proto-Algonquian

PL: plural

p.n.: personal name

s/b: should be

SG: singular

s.o.: someone

s.t.: something

TA: transitive verb, animate object

TI: transitive verb, inanimate object

XXX: segment of a recording not clearly audible

Naming the World

Introduction

An Ethnography of Language Shift Among the Northern Arapaho

Language Shift, Continuity, and Discontinuity

Bill was a Northern Arapaho man born in 1933, with whom I worked closely in my early days on the Wind River Reservation. He once told me that, in the old days, the St. Stephens Mission on the reservation would show cowboy and Indian movies on Saturday nights for the community for free. I asked him who the Arapahos cheered for when watching those movies, and he said, The cowboys! He also noted that when he was child, he and his friends would play cowboys and Indians down by the Little Wind River. He said, Nobody wanted to be the Indians. Then I asked him what language the kids used as they played: Arapaho! he said.

Anyone watching those children play during the 1930s would have assumed that the Arapaho language had a good future. In fact, it was the only language most of them knew. Yet appearances can be deceiving. As the communitys cheers and the childrens play preferences show, linguistic and social perceptions about the Arapaho language and Arapahoness were already in place that would soon contribute to a major language shift. More theoretically, there was a fundamental discontinuity already in place between the language practices of the community and its language ideologiesits beliefs about language, languages, and language behaviors.

Bourdieu talks of the distance between the order of practice and the order of discourse (1991:133), while Margaret Field notes the tension between cultural practice and discursive beliefs (Field 2009:40, with many additional references; cf. Meek 2010:39). This book is an ethnography of both language behavior and language shift among the Northern Arapaho, expanding on earlier studies (Gross 1951; Salzmann 1951; Anderson 1998; Anderson 2009), and a study of continuity, discontinuity, and the subtle and often surprising forms these take in the context of language shift (see Meek 2010:x, where she uses the term disjuncture in a way very similar to my discontinuity). Most broadly I am interested in what Marshall Sahlins calls structure[s] of conjunction (1985:125; see also Kulick 1992:1820 for a language-specific discussion).

The concept of continuity and discontinuity is problematic, however, as it supposes some clearly identifiable past and present practices and ideologies and thus a basic continuity as the grounds for comparison: the idea of a Northern Arapaho culture must be continuous at least, in order for statements about changes in its practices or ideology to be meaningful. I want to argue, however, that this is not the case. Instead, we must think more loosely about cultural and specifically linguistic resourcesthe Arapaho language in particular, and certain common language behaviors such as place naming, personal naming, creation of new words over time as new objects and concepts arise, and use of narrative and metaphor to make sense of the worldwhich are continuous. Bill recognized this himself. In his old age, he was often asked to provide personal names for young people. He would think carefully about the names as he believed they carried great power and history. But he noted that a lot of times [the young people] just, they just want a name, you know (laughs). Can you give me [an] Indian name? you know, like that (laughs). I said, Wait a minute... theres more to it... But you kids here, you probably dont know that. You just want an Indian name (Wiles 2002:8). Bill recognized the discontinuity between himself and many younger people in their cavalier attitude toward namesand the name giver. Most importantly, his use of the term Indian suggests that the young people in question are no longer engaged in Arapaho-specific linguistic and identity practices, but perhaps more oriented toward Pan-Indian goals.

Deborah House, in a study of language shift among the Navajo, notes that examinations of endangered languages and language shift often take an implicit or explicit culturalist perspective: a community has a language and a culture, and then shifts to another language (2002:xxv, 1921; see also Muehlmann 2014:58687). Here, I propose an alternative perspective, drawing specifically on practice theory (Bourdieu 1977; Ortner 2006) and the concept of a

Next page