This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior permission of the publisher. The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand

Preface and Acknowledgements

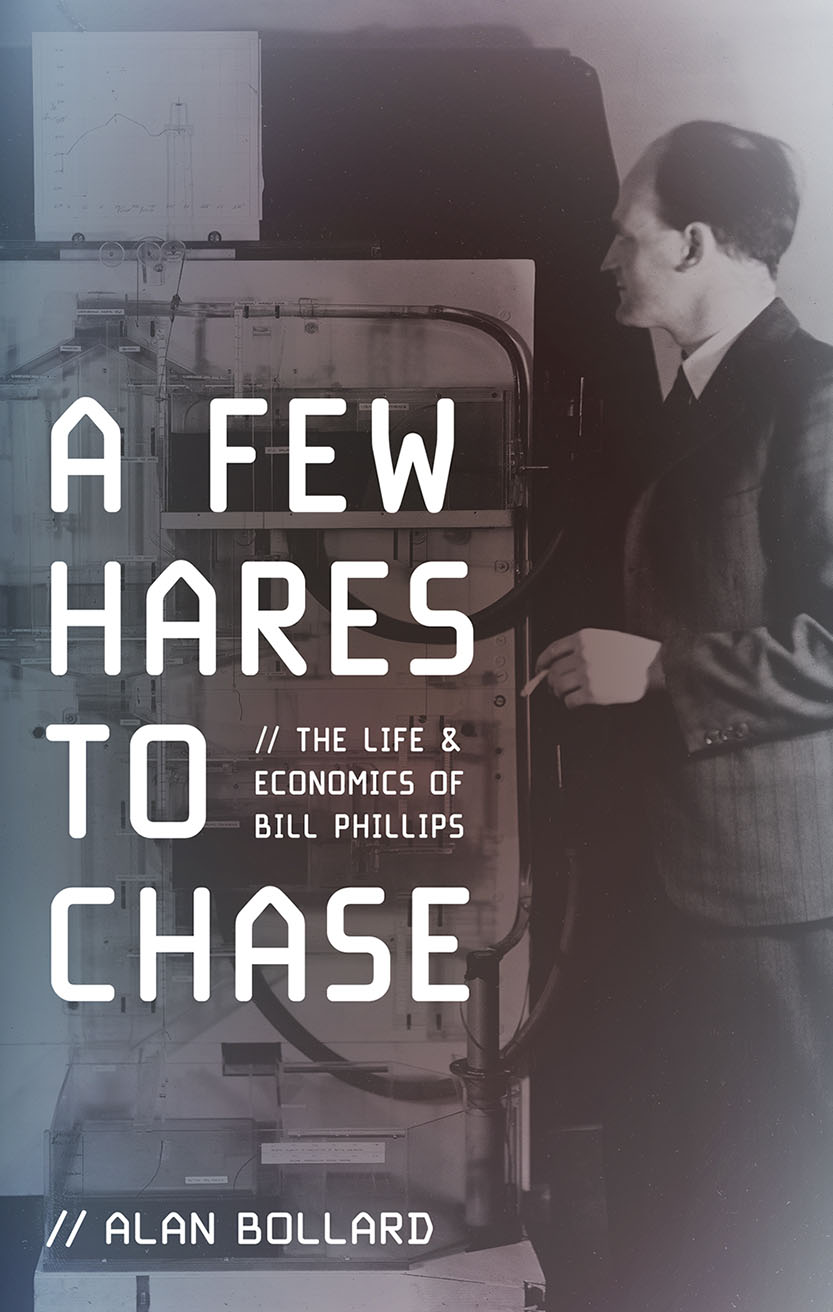

I did not do very much. I just put out a few hares for other people to chase. That was the comment that Bill Phillips made to a small group of colleagues who had gathered to honour him on his 60th birthday. Partly paralysed by a stroke, prematurely aged, and nearing the end of his life, that typically laconic remark summed up much about this quiet low-key but remarkable man.

And what a life! A young man from a remote farm in the Antipodes with little formal education, who went on to become a pioneer on the world stage of economics, just as that discipline was proving its worth in the real world in the mid-twentieth century.

The first part of this book tracks Bill Phillips as he goes off in search of adventure. It is a story of an unusual family, a rural childhood, an apprenticeship in the remote back country. He wanted to travel and learn about people, and he chose some of the most difficult parts of the world to do this. He experienced life and learning in London, war and fear in Singapore, subjugation and hardship in Java.

By the end of the war, Bill Phillips had had more than he wanted of physical adventure. The rest of his life was to be a cerebral adventure. The second part of the book is about his search for stability.

The search took him on a long journey. He taught himself economics, he built a pioneering computer, he did experiments on a model economy and used it to show how economic volatility could arise, he worked out how to stabilize this volatility, he built better models on the first electronic computersmaking them more realistic with inflation and wages, then reconfiguring the models to incorporate growthand he found sophisticated ways to estimate the effects of government policy. Just as his journey was cut short, he was seeking ways to apply these discoveries to one of the most extreme real world challenges of all1970s China.

My challenge in this book has been to present Bill Phillips life as a continuous story. He progressed from uneducated but enquiring youth to intellectual giant in a most unusual way. In less than a decade he progressed from a C-pass in sociology to become LSEs senior theoretical economics professor. He published only a little in economics, yet his papers remain among the most famous of the profession. He lived through a turbulent period of world history, and the ups and downs of that time influenced his quest. He had the mind of a restless savant, moving from problem to problem, yet he managed to do this in a coherent way, building his knowledge as he went.

Given how complex some of his work was, it has not been easy to write this Life in an engaging and accessible way, but that is what I have attempted. I have largely avoided graphs and avoided equations. Unless indicated by quotes, it is all my own voice.

It has proved challenging to get inside the mind of this man. He was quiet, self-contained. He kept his thoughts to himself, and he destroyed most of his papers. I met Bill Phillips when I was a graduate studenta small, quiet, balding man in a grey suit leaning heavily on a walking stick, hardly the sort to attract attention. But as I learned more about what this man had done, I realized that I had briefly rubbed shoulders with genius. I wrote this book to share that experience.

This book has been a long time in gestation. It probably started around 1987 when I secured the first full Phillips hydraulic machine from the LSE and had it re-constructed and transported to New Zealand. I spent many hours in an old garage puzzling over how to assemble it, and in doing so learned something of the genius of the designer. Over the years since then I have given many talks and written widely about this unusual man, his clever machine, and his other brilliant contributions.

During that time I have had help from many people including Carol Ibbotson-Somervell, Valda Phillips, Russell Phillips, Ray Phillips, Brian Phillips, Sarah Gaitanos, Brian Easton, Brian Silverstone, Gary Hawke, Bob Buckle, Tim Hazledine, Conrad Blyth, Jenny Morel, Neil Barr, Ozer Karagedikli, Kirdan Lees, Leo Krippner, Christie Smith, David Hargreaves, John McDermott, Sam Elworthy, Dick Miller, Sir Howard Davies, Gary Tee, Lord Meghnad Desai, Selwyn Cornish, Audrey Donnithorne, and the Archivists of LSE and ANU. For photographic material I thank Ailsa Allen, Jenny Phillips, Thelma Pattenden, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the London School of Economics, and the New Zealand Ministry of Culture and Heritage.

A number of people have helped me tell this story accurately and in context. My special thanks to Allan Sleeman, Vela Velupillai, and Brian Easton for detailed comments, and to several anonymous reviewers for advice. There is already some literature on Bill Phillips. A local history of the Te Rehunga district by Cath Cameron, the family memoirs by Carol Ibbotson-Somervell, the economic memoirs and collected papers edited by Robert Leeson, the Moniac conference papers edited by Vela Velupillai, the papers by Allan Sleeman, and the Phillips Curve anniversary conference papers organized by Grant Scobie have all been especially useful. These and all other references (including all Bill Phillips papers) are listed in the Bibliography.

I am grateful to the following copyright owners for permission to reproduce text: Professor Nick Barr, Cambridge University Press, Grubb Street Publications, W. Foulsham and Co., Professor David Laidler, The London School of Economics Archives and Special Collections, and also J. Wiley for permission to quote from Economic Journal and Economica. Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. For permission to use photographs I thank Ailsa Allen, Jenny Phillips, Thelma Pattenden, Carol Ibbotson-Somervell, Valda Phillips, and the London School of Economics, and the New Zealand Ministry of Culture and Heritage. Finally my thanks to Sam Elworthy of Auckland University Press, Adam Swallow and Aimee Wright of Oxford University Press, and to Kristin Scollay for their advice, editing, and support.

Bill said he only put out a few hares to chase. I have spent years in pursuit, acting like some sort of economic hound, aiming to track down these hares. I hope you enjoy the chase!

Alan Bollard

Contents

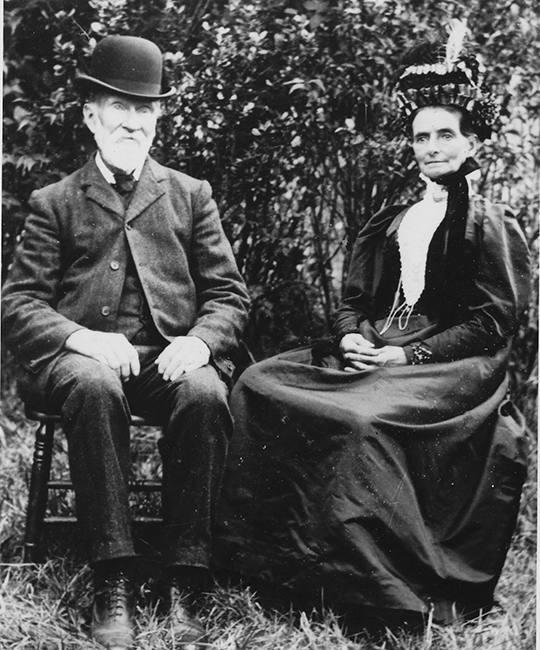

Plate 1. The grandparents: Herbert and Caroline Phillips, in Wellington, about 1910.