Sommaire

Pagination de l'dition papier

Guide

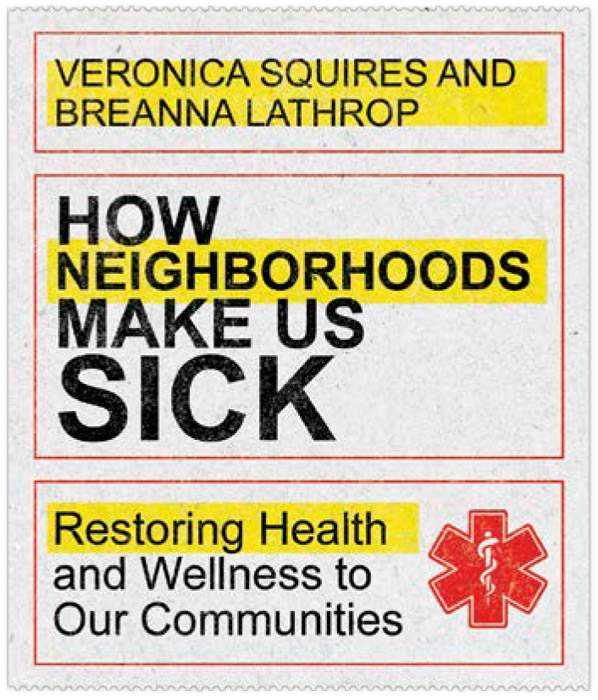

InterVarsity Press

P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515-1426

ivpress.com

2019 by Veronica S. Squires and Breanna L. Lathrop

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from InterVarsity Press.

InterVarsity Press is the book-publishing division of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA, a movement of students and faculty active on campus at hundreds of universities, colleges, and schools of nursing in the United States of America, and a member movement of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students. For information about local and regional activities, visit intervarsity.org.

All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from The Holy Bible, New International Version, NIV. Copyright 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide. www.zondervan.com. The NIV and New International Version are trademarks registered in the United States Patent and Trademark Office by Biblica, Inc.

While any stories in this book are true, some names and identifying information may have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

: Used by permission of The Good Samaritan Health Center, Inc.

Lyrics from The Unmaking: Written by David Hodges and Nichole Nordeman, from Nichole Nordeman, The Unmaking, Sparrow Records, 2015. Copyright 2015 Birdwing Music (ASCAP) Birdboy Songs (ASCAP) (adm. at CapitolCMGPublishing.com) / 3 Weddings Music All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Cover design: David Fassett

Interior design: Daniel van Loon

Images: apartment block: duncan1890 / E+ / Getty Images

shot of city map: Ugo Leonetti / /EyeEm /Getty Images

ISBN 978-0-8308-7335-7 (digital)

ISBN 978-0-8308-4557-6 (print)

This digital document has been produced by Nord Compo.

With admiration for our colleagues and contributors

who are making their neighborhoods healthier.

And for our children:

May our life work help narrow the

life expectancy gap for your generation.

FOREWORD

KERI NORRIS, PHD, MPH, MCHES

I n the race toward health equity, we have embraced many models in an effort to close gaps in health disparities for underserved and indigent populations. We know there is no one-size-fits-all solution. I submit that we must keep working toward health equity and embrace models that empower the communities we serve and move toward an all-inclusive policy and integrated care resolutions.

I personally believe that health equity is achieved when all levels of the socioecological model are addressed, but more specifically, the outer realms. We have spent so much time trying to change behavior that we forget once the behavior changes it is met with resistance at the institutional and policy levels. How can one be expected to maintain a positive change when met with obstacles at various levels? Once we embrace having everyone at the tablecommunities, housing, safety, urban planning, faith-based organizations, health systems, workforce development, legislators, and so forth, then we will move the needle on health equity. Collaborative partnerships are the most important tool along with policy change. That is how we win at health equity!

The real and lived experiences of Veronica and Breanna are indicative of how where you live impacts your mental and physical health, regardless of your socioeconomic status. They are dedicated servant leaders who have a heart toward health equity and made it their purpose to immerse themselves in communities with the greatest needs. I urge readers to forget the race of these women and do not liken them to well-to-do women who volunteer in disparate communities and leave it at donations and daytime exchanges with poor folks. This was no ethnographic study; this was the heart of Christ in two professional women who embedded themselves in walking the walk. Two professional women who now understand the communities they serve more than ever and who advocate for change even when it means challenging the status quo.

As a public health professional with over sixteen years of experience working in disparate and vulnerable communities throughout the United States and its territories, I compel you to see how models of health equity should begin to expand and encompass cultural humility and servant leadership and revisit community-based participatory programs. We can look to foundational initiatives, like the East Side Village Health Workers Partnership, and the local efforts highlighted in this book, such as the Good Samaritan Health Center and King Countys Office of Equity and Social Justice, to find models that need replicating throughout our communities and will finally bridge the gap.

CHAPTER 1

Two Journeys to the Inner City

But if I could turn life on its side

Go back and do everything right

Oh I think, I think

that I might.

JENN BOSTIC, SNOWSTORM

T he drive to the clinic in the morning is usually dark, the sun just starting to emerge over the heart of West Atlanta. Near the clinic, the roads become lined with abandoned houses and closed businesses. There are several corner shops and a few gas stations. Despite the early hours, there is always foot traffic and kids in uniform waiting at bus stops. Occasionally stray dogs wander along the road, and someone holding a sign is asking for money. Shortly before the clinic opens, the local jail procession drives past taking prisoners to work duty for the day. The landscape fits the story of urban poverty: unemployment, crime, and abandonment.

Yet, having worked and lived in the neighborhood for nearly a decade, we are aware of another story as well. The neighborhood is filled with vibrant church communities offering fellowship, meals, and social services in addition to weekly sermons. There is an urban garden movement with fresh produce hiding behind many rundown buildings. Several clinics, like the one we work in, offer health care services and health education. Progressive and creative learning communities like BEST Academy and KIPP are just blocks off the route to work. The neighborhood is filled with engaged community members with deep passion for their community and strong family ties. Yet the neighborhood is suffering.

When the Virginia Commonwealth University released their Mapping Life Expectancy project, we saw numbers that confirmed what years of clinical and community development experience had revealed. Life expectancy in this West Atlanta zip code is thirteen years less than life expectancy on the more affluent side of town. A twenty-minute drive within the perimeter of Atlanta creates a life expectancy gap of thirteen years. This finding wasnt unique to Atlanta. From a sixteen year gap in Chicago to twelve years in St. Louis and twenty years in Philadelphia, life expectancy gaps persist throughout US urban areas. How is it possible that people living within the same city could have such drastic differences in life expectancies? How can residents in neighboring zip codes have such distinct differences in mortality?