Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

For Karen

and Cyndy

and all our angels

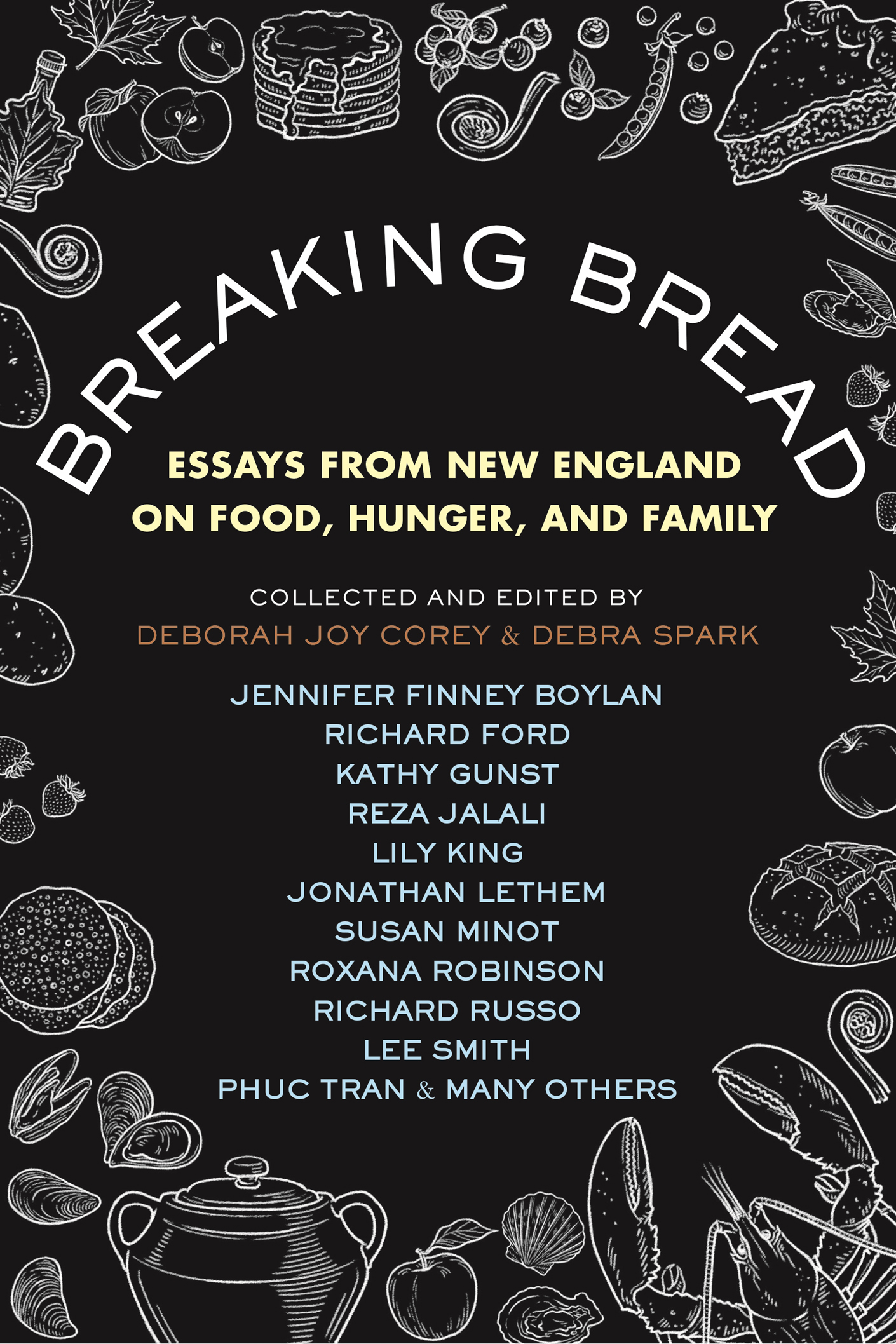

PREFACE

Deborah Joy Corey

A FEW YEARS AGO , I was hearing more about hunger increasing in Maine, and so I began to do some research, thinking that I would write an essay. I visited nearby food pantries and shelters. One shelter director said that her pantry rarely receives fresh vegetables or jams and jellies or brand-name peanut butter. She also told me that many people she serves do not have happy food memories. Some of the children have never experienced home cooking. Their appetites are driven by growling bellies, not the smell of a roasting chicken, or a simmering stew, or chocolate chip cookies baking when they arrive home from school.

I also talked to local church and community leaders, who told me that members of my own village often did not have enough food. All of them, with the exception of a few who are elderly or chronically ill, have jobs and work hard. Upon learning this, what had started as a research mission became a mandate to help.

In February of 2019, I asked Paul and Dixie Gray, leaders at the church that I attend, if I could use an empty space on church property to build a garden. The space had once been a playground for a daycare, and that seemed to ordain it for growing vegetables for local families. The Grays were immediately supportive and have remained so.

M ARCH OF 2019 was a cold month. On the first day, my beloved niece Karen died suddenly of an aneurysm. She had the most beautiful blue eyes. She was a caring mother, an experienced gardener, and a wonderful cook. Each morning when I woke, the frost had made beautiful and intricate angel wings on my bedroom window. For many mornings after her death, I studied the frozen angel wings, the rising sun shining through them and making them gleam as they melted away. One night, I dreamt of an angel with mighty blue wings the color of Karens eyes.

This dream sustained me while forming Blue Angel. I began to talk to local farms to see if they might help provide fresh produce for families. Amanda Provencher of King Hill Farm was the first on board, and others followed.

Later, I asked my community to donate from their home gardens, and boy, have they delivered! Others have given financially, some water and weed the church garden, some bake bread and cakes and cookies. Village chefs make soup and stews, and the local markets and restaurants giveall leaving their donations on my porch. By the grace of those blue wings, it continues.

Since the spring of 2019, Blue Angel has been making weekly deliveries of healthy food to nearby homes. From porch to porch, it goes. Often, we have extras that we give to local daycares and food pantries. At a shelter in Orland, Maine, we have set up a free summer vegetable stand. Some of the families that we help now plant their own gardens and give back to Blue Angel. Our youngest gardener is seven years old. Her name is Fiona.

T HE OFTEN - USED PHRASE food insecure seems to soften the crisis of hunger that I have witnessed. Ravenous. Starving. I could eat a horse and chase the riderthese are the things that I say at the first twinge of hunger. I never say, I feel a little food insecure. The low impact of this language is dangerous. It provides comfort to the wrong people, allowing the fortunate to maintain an illusion that hunger in our community is a mere inconvenience, rather than an immediate crisis.

The fact that many do not have fond food memories has stayed with me, making me examine my own food memories and wonder about those of others. What if we were to share our memories with one another, the good and the bad? What if we did something to start a broader conversation? Could sharing our stories be the catalyst to change, as it so often is? And, so, I asked my writing community to take the lead by submitting essays about their food memories.

The generous response was so overwhelming that I soon knew I needed a coeditor. I partnered with an old friend, Debra Spark. Debra and I met many years ago when we were both young writers living in Boston. I am so grateful to her and to all the writers who have shared their work. By offering their stories regarding their food heritage, they are breaking bread through story, and they are supporting Blue Angels mission. From the bottom of my heart, I thank them.

www.blueangelme.org

THE RHUBARB ROUTE

Wesley McNair

On a spring evening in between the black fly season

and the first mosquitoes, as the red stems lift

their broad leaves like scores of tilted umbrellas,

I call them on the telephone of my mind and drive

bagfuls of rhubarb down through the town, past

the white revenants of the Grange Hall and the closed

library, past the house lots and the treeless modulars

where they have no use for rhubarb, turning at last into

a wide driveway while little Herman, alive as anyone,

comes out of his old farmhouse with his chesty walk

to take two bags inside to Faye, enough for a whole

year of pies and red-Jell-O cobblers, then drive the back

way along the river, by the oaks and sumacs gathering

the shadows of twilight, to swing in beside the dead

school bus of Trues cowless farm and see old Billy,

before his legs gave out, who loved rhubarb almost

as much as his long-lost mother, take the biggest bag

of it into his arms and carry it up the steps of his porch,

leaning on the rail to wave goodbye. Goodbye to Billy,

goodbye to little Herman, goodbye to the Gagnons,

who laugh in the deepening dusk about eating sticks

of rhubarb right from the patch as kids, goodbye

to my old neighbor Ethlyn in the house on the corner,

empty for two years, who all the same calls out

Hello from somewhere inside when I knock, Hello,

Im here, and suddenly she is here next to me behind

the screen, smiling because Ive remembered her again

on this spring evening with fresh rhubarb, which

she holds up to her face, breathing it in with a long

breath before she turns and goes back into the dark.

THE ZEN OF FIDDLEHEADS

Cathie Pelletier

F OR THREE OR four weeks each spring, a small green miracle appears along New Englands shady riverbanks, brooks, and damp marshes. In its first few days of life, before it has time to unfurl into the ostrich fern it really is, it looks like the scroll on the tip of a fiddle. Botanists call it Matteuccia struthiopteris, but we northern Mainers know it as the humble fiddlehead. It is born swaddled in a brown papery chaff carried over from the previous autumn. With southern Maine being so tourist-centric in the summers, fancy recipes using fiddleheads have made their way into print over the years. There are quiches and omelets, Gruyre tarts and sauces, saffron soups and edamame salads. Some cookbooks have fiddleheads in league with