AUTHORS NOTE

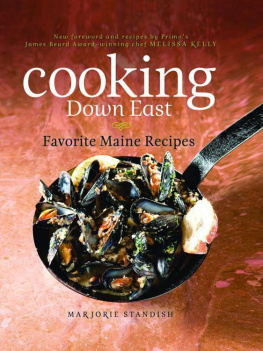

Kenneth Roberts was at work on Trending into Maine when I became his secretary. One of the chapters in that book dealt with the dishes which he, as a boy on a Maine farm, fondly rememberedsuch dishes as fish chowder, baked beans, corned beef hash, fish balls, finnan haddie, coot stew, tomato ketchup, chocolate custards.

A few months after that chapter was written it was published in the Saturday Evening Post; and for weeks after its publication I opened and helped answer letters from homesick, helpful, or indignant residents and ex-residents of Maine.

They wanted to know why Mr. Roberts hadnt mentioned lemon pie. They were profoundly pained because he had said nothing about salt fish dinner. Where, they wanted to know, was the recipe for blueberry pie? For what reason, they demanded, did he put six tablespoonfuls of salt in his ketchup recipe, and why didnt he stick to writing novels instead of encroaching on a womans provincethe kitchen?

Ladies who had licked their first frosting spoon in the shadow of Mount Katahdin, on the fir-clad points of Boothbay, along the snakelike windings of the upper Kennebec, in salt-box houses on the edges of Kittery meadows, on the hill slopes looking out across the emerald islands of Casco Bay, took pen in hand to tell Mr. Roberts about Aunt Emmas marvelous recipe for oxtail soup; Grandma Perkins stimulating cucumber relish; Cousin Jane Weavers miraculous cracked pitcher for pancake batter; Cousin Marys succulent red flannel hash; Dr. Emmons wifes manner of preparing Indian pudding; Captain Stones recipe for fried pies; Great-aunt Carries hermits.

Keep those letters separate, he told me. Wed better have some of that red flannel hash. I havent had any since I was eleven years old. Get my grandmothers cookbook and see whether she made it the same way.

Some of them annoyed him. Sugar in ketchup! he protested. That womans family werent seafarers or farmers. They were city folks! Their tastes were ruined by tea parties! Sweet pickles! Bah! Sugar in ketchup! Sugar in beans! Bananas and cherries on a salad! Nuts! Thats not the sort of good Maine food I used to know!

Answering these letters, copying them and checking them in Grandmas cookbook led to other thingsled to consultation with far-off aunts and cousins over recipes used by Grandmas cook Katie, Aunt Luties cook Susy, Aunt Fannys Maggie, Cousin Isabels Addie.

Our file of cooking letters grew. There were letters from educators, male and female; from Africa; from the Dutch East Indies; from England, New Zealand, Mexico, and almost every state in the Union, all dealing with Maine foods.

Cookbooks written in ink that had faded to the color of pallid coffee were exhumed from attics; from behind spice tins in kitchens that hadnt altered, except for the stove, in half a century.

Sea captains wives lodged information concerning dishes discovered by them in faroff ports and brought back to Maine to provide exotic company for baked beans and hash. Residents of Maine whose forebears had come from Sweden to settle in Aroostook County, from Finland to work the granite quarries near Tenants Harbor, from Greece and Syria to conduct small businesses in Biddeford and Portland, from Yorkshire and the Midlands to work in the woolen mills of Sanford and Saco, obliged us with recipes that had, they said, been eagerly adopted by neighbors who were suspicious of all other foreign dishes.

French Canadians have moved down into Maine in great numbers; and French-Canadian concoctions that must have been well and favorably known to the Jesuit Fathers have seemingly become common property in many sections of the state, so that they are now Maine foodsand those addicted to them protest sharply when they arent included among Maines culinary triumphs.

Out of all those letters, those tattered family recipe books, those blank-books bulging with personal notes from long-dead ladies explaining unusual methods of handling lobster stew, potato soup, corn muffins and other delicacies, came this book, which is a fairly comprehensive compilation of recipes that have long been approved by the rugged and straightforward people of a peculiarly rugged state.

Marjorie Mosser

KENNETH ROBERTS ON DIET

A novelist, in consulting references on any given subject, is usually forced to discard the majority as inaccurate, biased, unreliable or untruthful, and to retain a few dependable ones as his chief sources of information. This is because too many writers of reference books are careless about their facts, and willing to conceal evidence in order to make a good case for their unsound theories.

Books on diet ought to be different; for most of them are written by medical experts who have studied for years to find out exactly what happens to seven cents worth of liver when it meets a Welchs bacillus in the upper colon of a sedentary worker aged forty-five.

Diet books ought indeed to be different; yet when I first looked into some of them, I found myself entertaining grave doubts.

From each book, for example, I learned that all diets, except the one advocated by the author of that particular book, are either based on the erroneous ideas of a faddist, or are downright dangerous. I learned that I had eaten incorrect foods all my life and must do something about it in a hurry. What that something should be, however, was a problem.

From a cursory survey of the most advanced diet books I gathered that nearly every disease in the world is not only the result of eating improper foods, but also the result of eating proper foods in improper combinations.

I further discovered that although a person may consider himself in perfect health, and may feel comfortable and happy, he isunless he is eating foods that the diet books say he ought to eatas effectively poisoned as though nurtured for years on poison-ivy salads with bichloride-of-mercury dressing.

I also learned that almost every sort of illnessaccording to the most advanced school of diet thoughtcan be prevented or cured by proper diet; and that the only way in which any person can save himself from a fatal sickness is by ceasing to eat nearly everything to which he has hitherto been addicted and devoting the rest of his life to devouring foods he wouldnt ordinarily eat except on a bet.

I learned, with considerable distress, that the person who permits himself to eat starches, meats and sweets must be in a constant state of internal ferment. Not only is intestinal fermentation inevitable, but those who suffer from it are nervous, timid, afraid, irritable and suspicious; they are quick-tempered, disagreeable and easily offended; under the influence of intestinal ferment a splendid mind often loses its faculty of reasoning and thinking.

I discovered, with steadily growing apprehension, that if a person is so ignorant as to permit fermentable foods to pass his lips, he is doomed, because no amount of exercise, medicines or outdoor life can counteract the harmful effects of fermented foods. They give him acidosis; and what acidosis does to him, in a quiet way, almost passes belief.

Acidosis is too large a subject for me to handle, in these few notes, except in the sketchiest manner. Not even the authors of the diet books are able to handle it satisfactorily. However, all of us are suffering from acidosis; and so far as I can tell, everybody has suffered from acidosis since the beginning of the worldunless he has been so happy as to stumble on the proper diet.

Among the unfortunates who must have been afflicted with it are Chaucer, Martin Luther, Julius Caesar, Christopher Columbus, William Shakespeare, Michelangelo, George Washington, Napoleon Bonaparte, and all other great leaders, thinkers, fighters and philosophers, as well as everybody who is or has ever been afraid of thunderstorms.