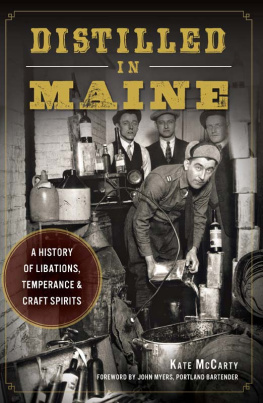

Published by American Palate

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Kate McCarty

All rights reserved

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.328.8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015940379

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.775.6

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To my family

FOREWORD

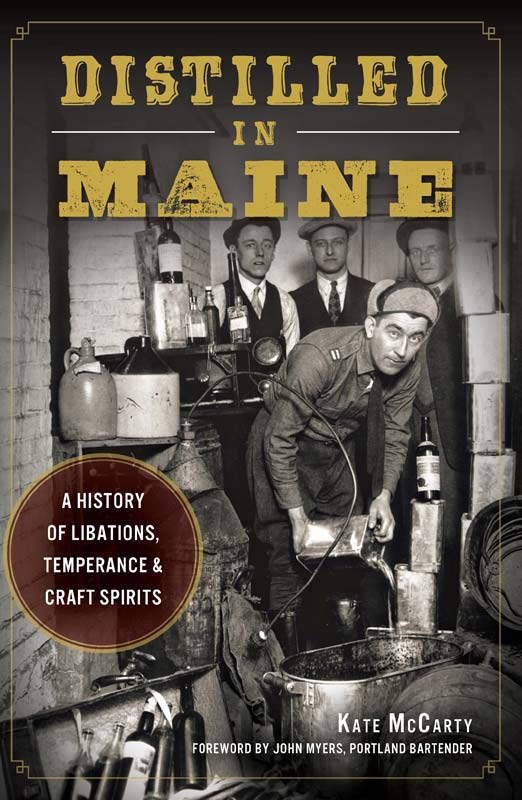

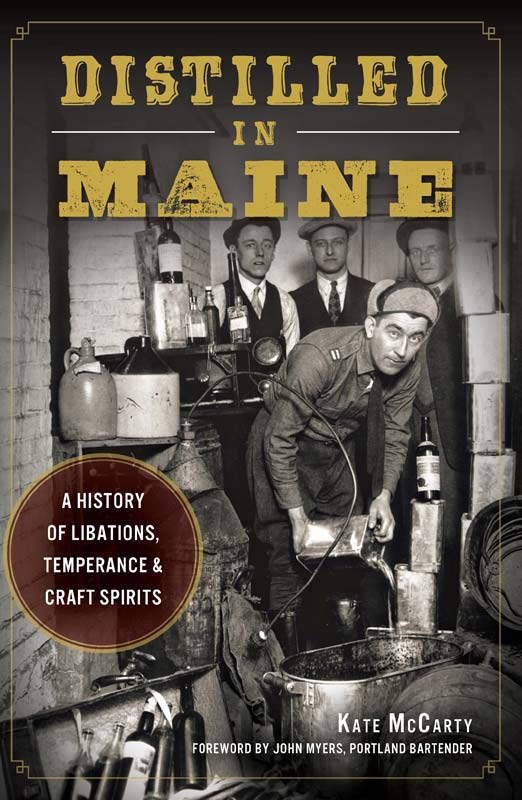

Ahalf dozen or so years ago, one of the exceedingly popular liquor brands at the time approached me to conduct a historical and boozy walking tour of Portlands Old Port, pointing out along the way some important and interesting spots in the history of drinking in Port City. Before I fully realized what I was in for, Id said yes.

Because heres the problem: its in the very nature of the bar and saloon business to be ephemerala knowing forgetfulness is its stock and trade after all. Besides, printed menus in the saloon era were simply not a thing, and America was in its pre-regulatory phase. So there are few, if any, records of interest. As cocktail historian nonpareil David Wondrich points out in Imbibe:

Unfortunately, there was no Homer to record the names and deeds of bartenders. Other disciplines of similarly louche character found their poetsand there was no shortage of what was known as convivial or jovial literature, books about social drinkers and their conversation. But the nineteenth century brought forth no American Bariana, no chronicle of the men behind the bar, their sayings and their doingsWe might catch occasional glimpses of them in the murk, tossing drinks from cup to cup before a bewhiskered and thoroughly appreciative crowd, but beyond that they were enigmas.

With the exception of the gin palaces and extravagant hotel bars in the major urban centers, saloons and bars (and their clientele) existed in a sort of nebulous and squalid demimonde, ignored and tolerated by most, vilified by the rest. Its just not the kind of subject matter the scriveners of the day wanted to attach their pens to.

But Portland in particular, and Maine in general, presents yet another problem. The most remarkable thing about drinking in Maine is just how thoroughly it was outlawed. With but a few scant years in the 1850s, Maine had absolute prohibition from 1851 until national repeal in 1933. Think about that for a minute.

For more than eighty years, it was illegal to have a cocktail. And were not talking about just any eighty-year drought either. These fourscore years cover the entirety of the Golden Age of the American Cocktail. The first cocktail book, Jerry Thomass Bar-Tenders Guide, was printed in 1862. His chief rival, Harry Johnson, published The New and Improved Illustrated Bartenders Manual in 1888. The martini and the Manhattan were born. This is the primordial ooze from which the au courant craft cocktail movement would emerge. And yet, in Portland Town, its dry, dry, dry.

Well, at least damp. As Will Rogers said, Prohibition is better than no liquor at all.

So when Kate told me her follow-up to her book Portland Food: The Culinary Capital of Maine was to be a history of alcohol in Maine, I winced a little. Maybe a lot. It might have been more like a cringe. But she got after it, as they say, and got the better of it, toomaybe even made it look as easy as falling off a wagon. In this whirlwind tour, youll catch a glimpse of our early alcoholic republic, the weird Progressive forces (and even weirder Neal Dow) that made prohibition one of Maines biggest exports and the smugglers and scofflaws who scuttled it. In an O. Henryesque ending, youll meet the makers (and shakers) driving the thriving craft distilling movement we have today.

Weve indeed come a long way since the days when Irving S. Cobb encountered this criminal:

In the name of the julep I have seen high crimes and flagrant misdemeanors committed[O]nce, in Farther Maine, a criminal masquerading as a barkeeper at a summer hotel, reared for me a strange structure that had nearly everything in it except the proper constituents of a julep. It had in it sliced pineapple, orange peel, lemon juice, pickled peaches, sundry other fruits and various berries, both fresh and preserved; and the whipped-up white of an egg, and for a crowning atrocity a flirt of allspice across that expanse of pallid meringue. When I could in some degree restrain my weeping, I told him things. Brother, I told him, between sobs, brother, all this needs is a crust on it and a knife to eat it with, and it would be a typical example of the supreme effect in pastry of your native New England housewifes breakfast table. But, brother, I said, I didnt come in here for a pie, I mentioned a julep; and you, my poor erring brother, you have done this to me! Go, I said, go and sin no more or, at least, sin as little as possible.

Irving S. Cobbs Own Recipe Book, 1934

Cheers!

JOHN MYERS

Portland, Maine

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to the staff of the Maine Historical Society research library, Kelly Page at the Maine Maritime Museum library, Don Lindgren of Rabelais Books, Cathleen Miller of the University of New Englands Maine Women Writers Collection and Raminta Moore of the Portland Public Library for providing research assistance.

Thank you to Keith and Constance Bodine, Luke Davidson, Karen Farber, Bob and Kathe Bartlett, Chris Dowe, Jessica Jewell, Ned Wight, Eric Michaud, Dave and David Woods, Bruce Olson and Steve and Johanna Corman for sharing your stories and spirits with me. Thanks to Sean Wilkinson and Trey Hughes of Three Sheets Mfg. blog (threesheetsmfg.com) for providing many of the cocktail recipes that follow each chapter. Thank you to Patrick McDonald and John Myers for your time, ideas and many inspiring drinks.

Thank you to my friends who suffered through many rounds of research cocktails and especially to Amy Clearwater for your help with editing. Thank you to Greta Rybus for lending your incredible eye to many of the photographs for this project. Thank you to the readers of my food blog, The Blueberry Files, and to Katie Orlando for once again suggesting we work together. Thank you to my dear boyfriend, Andrew, who enthusiastically embraced my mission to expand our homes liquor cabinet. Thank you to my family for always believing in me and for letting me know it.

INTRODUCTION

At the corner of two cobblestoned streets, a block from the Portland, Maine waterfront, sits a historic, three-story brick warehouse. Inside, behind the cozy, first-floor bar, several bartenders clad in plaid shirts (this is Maine, after all) are busy pouring, mixing, squeezing and shaking. Above the din of ice in metal shakers, customers order cocktails whose names havent been on the lips of drinkers since the end of the nineteenth centuryCobbler, Corpse Reviver, Knickerbockerall classic cocktails first printed in Jerry Thomass 1862 Bar-tenders Guide: How to Mix Drinks and given new life in the hands of todays bartenders.

Next page