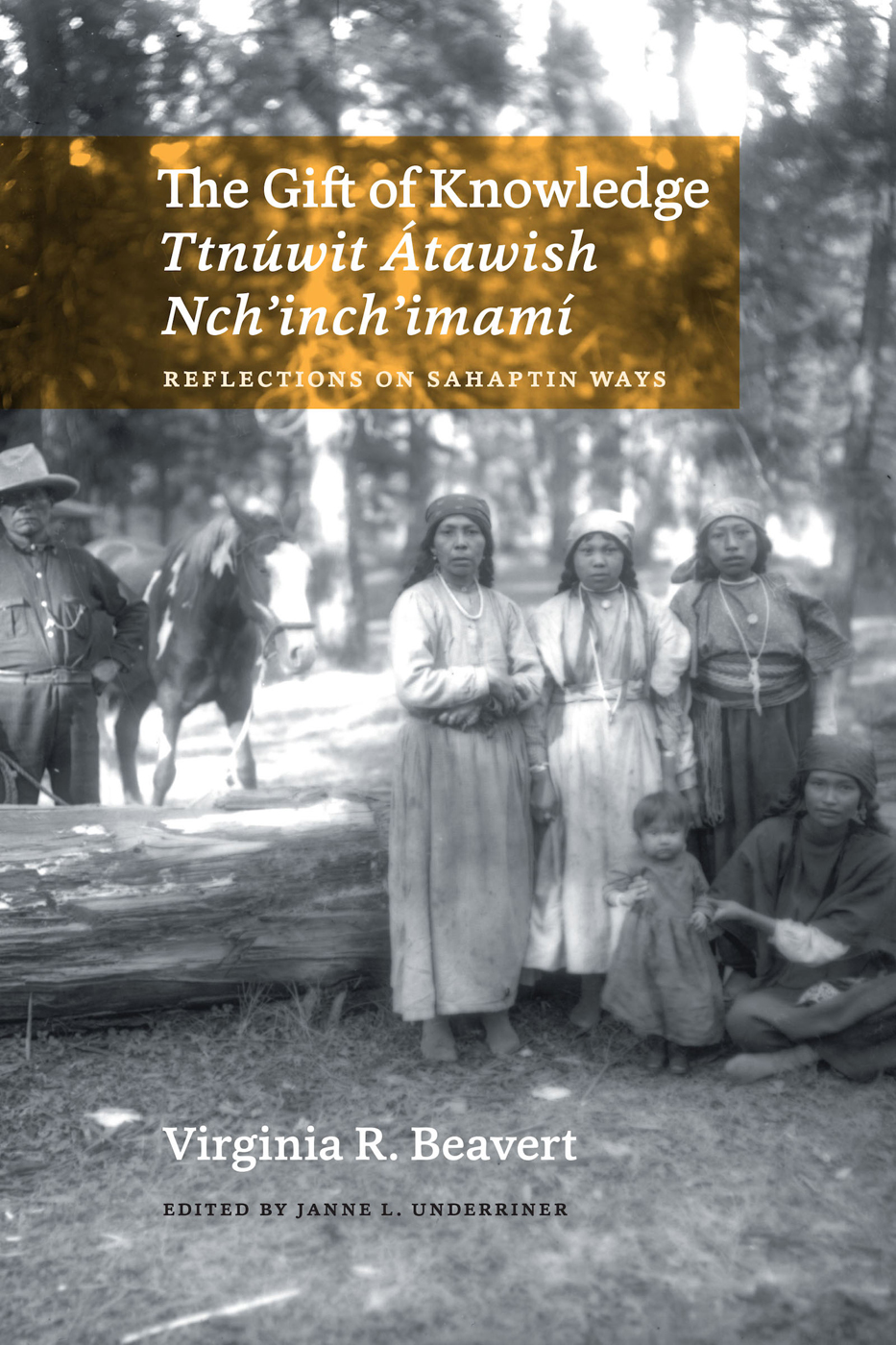

The Gift of Knowledge / Ttnwit tawish Nchinchimam

The author with her mother, Ellen Saluskin (Hoptonix Sawyalilx), and stepfather, Alex Saluskin, ca. 1941. Courtesy of Virginia Beavert Family Photo Collection.

The Gift of Knowledge / Ttnwit tawish Nchinchimam

Reflections on Sahaptin Ways

VIRGINIA R. BEAVERT

Edited by Janne L. Underriner

University of Washington Press

Seattle and London

The Gift of Knowledge / Ttnwit tawish Nchinchimam was published with the assistance of a grant from the Naomi B. Pascal Editors Endowment, supported through the generosity of Nancy Alvord, Dorothy and David Anthony, Janet and John Creighton, Patti Knowles, Katherine and Douglass Raff, Mary McLellan Williams, and other donors.

| This book was also supported by a generous grant from the Tulalip Tribes Charitable Fund, which provides the opportunity for a sustainable and healthy community for all. |

Copyright 2017 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in the United States of America

Design by Katrina Noble

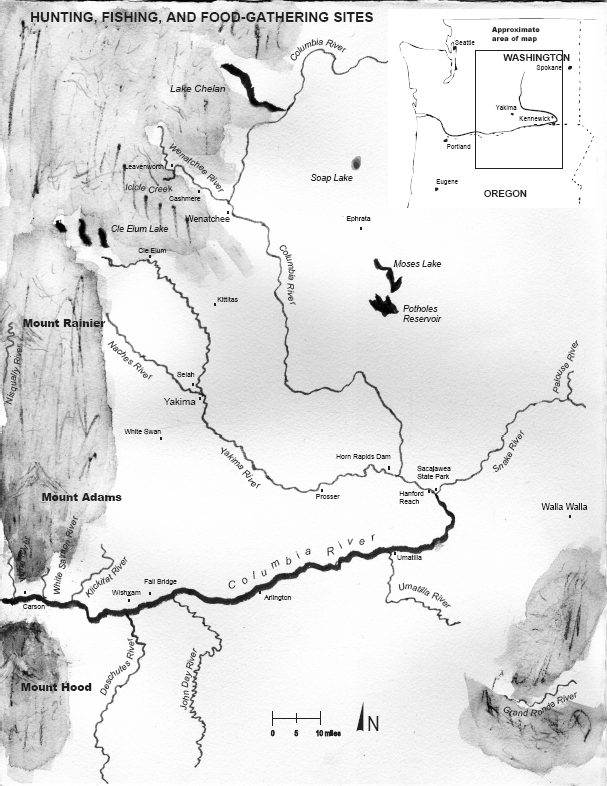

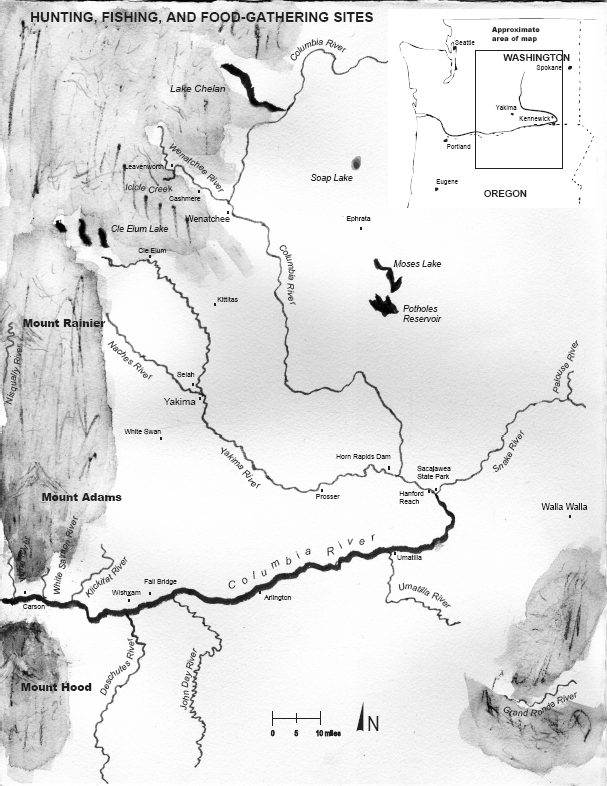

Map by Robert Elliott

Composed in Minion Pro, typeface designed by Robert Slimbach

21 20 19 18 17 5 4 3 2 1

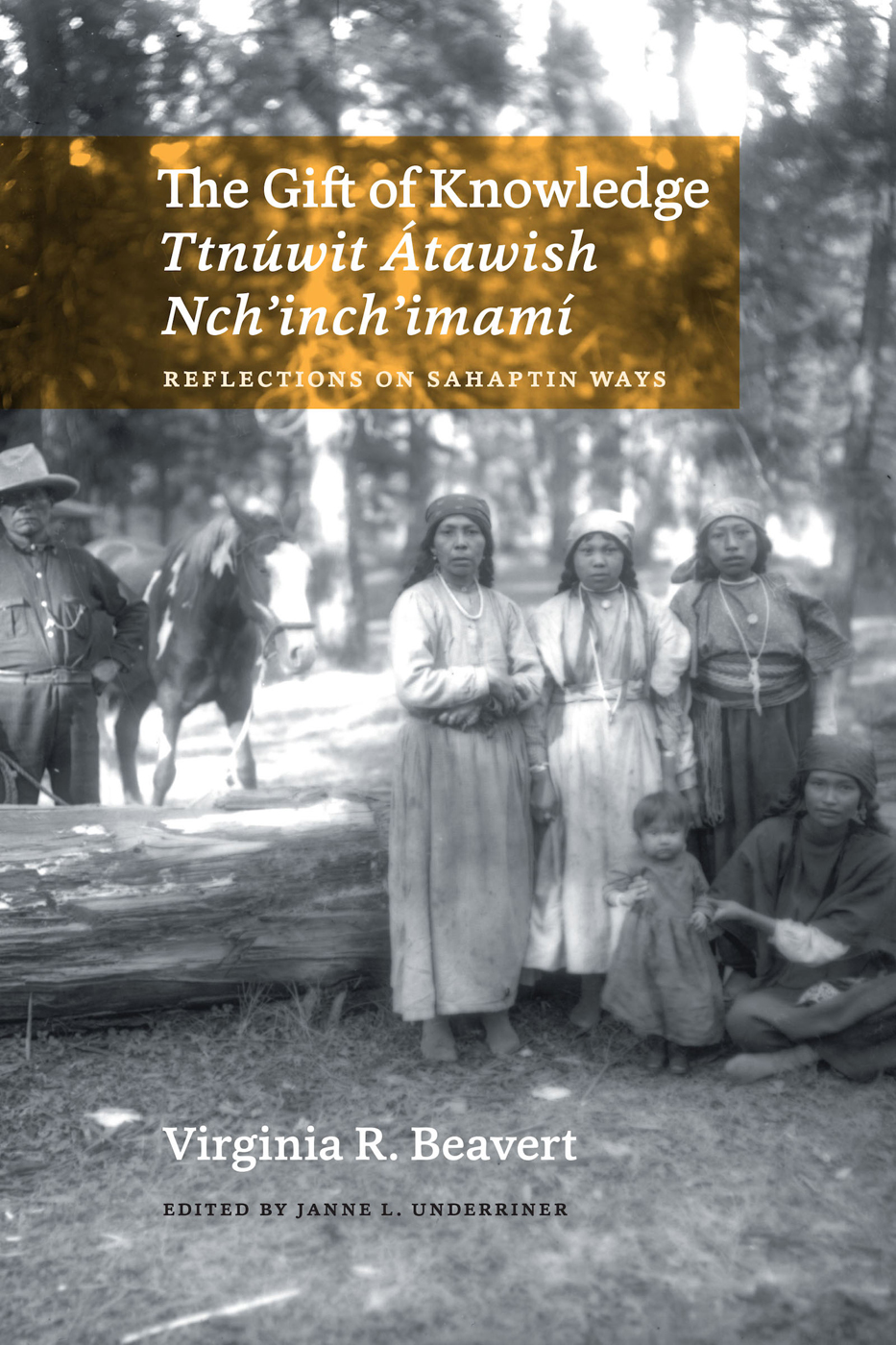

Cover photograph: Wwtuktpa (At Camp), ca. 1922 (the author is the child and her mother is seated). Courtesy of Yakama Nation Museum

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

University of Washington Press

www.washington.edu/uwpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

To Ronald, Julie, and Brian Saluskin, and all of their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, to Rudolph Saluskin II (deceased), and all of his children and grandchildren, and to Steven Saluskin.

Contents

Illustrations

Preface

This is the story of my life and the traditions of my family. From birth I was immersed in the Ichishkin language, culture, traditions, history, and modern life of the Sahaptin People, who reside in the Pacific Northwest of the United States of America. All of these elements are related to the importance of maintaining and preserving the foundation of Indian life. One wise man said, Without language there is no culture, without culture there is no language.

This is also my way of answering questions asked of me over the years by people in my community, linguists, and others. Writing has enabled me to gather in one place language that I feel is slipping away from my people. Young people are the future caretakers of this country. It is essential that they obtain an education in science and linguistics to keep pace with the modern world, to protect their natural environment and preserve their identity. Soon, the Sahaptin Elders will be gone and no longer available to consult about language and culture. This is my contribution to the younger and future generations. It is for their benefit that I write this.

I begin by addressing the history of academic research on my language from the perspective of a Native person who has been involved in this work as an assistant to non-Native researchers and now as a linguist myself. I talk about my language and how it works from the perspective of a Yakama person who has spoken and used the language her whole life, and about my path to becoming a linguist and educator.

Subsequent chapters are about my early life and the traditions in which I was raised. I first reflect on growing up through stories of my family, my early traditional and public schooling, and descriptions of traditions and the areas where I was raised. I then detail some of the most basic ways of our ancient culture and lifeways through description of the circle of life, from conception to death. Finally, I discuss other parts of traditional life: sweathouse, bone game, horses, and foods. In an appendix, I offer suggestions to scholars and academic researchers, Native and non-Native, working in the field of Native language documentation, preservation, and revitalization. An IchishkinEnglish glossary lists terms used in the text for learners and teachers. It is my hope that they will be used in the classroom and at home.

I write this for the Ichishkin-speaking communities in hope that this documentation of our lost traditions will provide a resource from which to learn our ancestors ways and language. Detailing the traditional practices offers a much needed historical and social accounting of each. And explaining the words we use to talk about our traditions and how these words explain the deeper meaning of what we do gives our communities the vocabulary they need to practice our traditions. Included are various dialects and ways shared by other Ichishkin-speaking communities, as well as texts and descriptions of dances, songs, and practices in Ichishkin.

This work contributes to the fields of sociolinguistics and theoretical linguistics, as well as historical and cultural anthropology. Despite the best efforts of some anthropologists and linguists, all earlier academic work done on Yakima Ichishkin was conducted by researchers from outside the community and is inevitably seen and presented through the lens of the English language, Euro-American culture, and the Western tradition of objective scholarship. I am in a unique position to present the research on my language as a contribution to academic scholarship but from a very different perspective: that of a Native speaker and scholar. Implicit in my view of scholarship is the way researchers should work with Native people; therefore, I address how linguists can better work with community members, as well as the protocols and etiquette expected by Native people in working with non-Natives.

In cowriting Ichishkin Snwit: Yakama/Yakima Sahaptin Dictionary with Sharon Hargus (Beavert and Hargus 2009) and working together with Joana Jansen to create A Grammar of Yakima Ichishkin/Sahaptin (Jansen 2010), it became clear to me that I wanted to document the Yakama traditions I was raised in. In doing so here, I have included dialects and practices shared by other Ichishkin-speaking communities to preserve their language so these communities will benefit from this work. Practices distinct to each Ichishkinspeaking community are becoming diluted, and this is causing confusion among younger generations.

It is my hope that this book will better inform Ichishkin communities about language and traditional protocols. For example, our Elders tell us that our Ichishkin language is needed to enable us to obtain the natural medicines we need to heal our bodies and to gather our roots and prepare our foods. We must speak our language to the plants when we gather. Ceremonies must be conducted in Ichishkin. These things people do not understand anymore. So I include the language necessary to carry out traditions as our ancestors did, as well as descriptions of changes and variations in practices and of female and male language when practice is affected by gender.

Next page